Resident Readiness General Surgery (72 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Haytham M.A. Kaafarani, MD, MPH, Brian C. George, MD, and Hasan B. Alam, MD

Mr. Gossman is a 55-year-old gentleman who was marching in a bagpipe band when he was struck by a beer truck. On arrival to the emergency department he is complaining of abdominal pain. He is hemodynamically stable with diffuse abdominal tenderness. The remainder of his exam is unremarkable.

Based on your evaluation you believe that it is safe to proceed with a CT scan.

1.

Who should you talk to before ordering the CT?

2.

Should this patient get oral contrast and/or intravenous (IV) contrast?

3.

After the CT is completed, is there anything that you do before reviewing the film with radiology?

4.

What window should you use to look for free air?

5.

In this patient, what does a fluid collection of 40 Hounsfield units (HU) most likely represent?

ORDERING AND INTERPRETING A CT SCAN OF THE ABDOMEN: THE BASICS

As an intern in general surgery, you will often be asked to “pull up” the CT of the abdomen. Although no one expects you to become the expert on reading abdominal CTs in your first year of residency, your ability to understand the basics of ordering and interpreting a CT can help save a patient’s life.

Answers

1.

Knowing when (and whether) to order a CT scan is an important skill to acquire during your internship.

The two rules of thumb are:

A. Do not order a CT without talking to your senior resident first. This rule is not made to simply create unneeded hierarchy. Your senior resident might know some operative details that are essential to understand how your patient is doing, and the resident might have a lower or higher threshold for ordering an abdominal CT based on intraoperative details or findings.

B. Always ask yourself how the CT will change your management. This second rule is a general one that you should apply every time you are ordering any test on your patient. No test, especially radiological, comes without a

price. An unneeded abdominal CT results in unwarranted patient exposure to radiation, and cumulative radiation exposure is well known to increase the risk of malignancies in the long run. In the short term, a trip to the CT for patients with lines and tubes is a big burden for the nurses, and is not without its own risks: a chest tube might get dislodged, or the patient might be agitated thus requiring some conscious sedation, a further risk. So, always ask yourself “what will I find on the scan (or any test) that will change my current management?”

2.

You answer your pager and hear: “Dr. Smith, radiology is on the line asking what kind of contrast you want for the CT scan you just ordered?” The answer is not that complicated if you remember four simple rules:

A. If your patient has intact kidneys and normal creatinine, IV contrast is almost always helpful. If your patient has acute or chronic renal failure, think twice before you order IV contrast. IV contrast is nephrotoxic, especially in elderly diabetic patients. If you suspect free air, a noncontrast CT (ie, without IV or PO contrast) will give you the answer. Otherwise, IV contrast, in general, allows better tissue and organ visualization.

B. If you need to evaluate the anatomy of the GI tract or are looking for an anastomotic leak, PO contrast will help a lot. PO contrast delineates intraluminal anatomy. Observing contrast within the appendiceal lumen is one of the radiological signs that almost “rules out” acute appendicitis. A tachycardic gastric bypass patient may have a leak. On the CT images, extravasation of the PO contrast out of the gastric pouch or the jejunojejunostomy is an essential finding to diagnose this complication.

C. If the pathology you’re looking for is in the colon, a per rectum (PR) contrast can be helpful. Talk to your senior resident and radiologist about it. PR contrast can help diagnose a low rectal anastomotic leak, a colonic stricture, a colonic mass, or even acute appendicitis.

D. If the pathology you’re looking for is intravascular, a different IV contrast dose and protocol are indicated. For the diagnosis of mesenteric ischemia, IV contrast is essential. Similarly, if you suspect a portal vein or a mesenteric venous problem, there is no direct IV access to the mesenteric venous circulation so you need to obtain much later images (different radiological protocol). The dose, timing, and protocol of IV contrast needed to visualize the arterial or venous system are very different; talk to the radiologist—he or she is your friend, and make sure he or she understands what you’re suspecting.

3.

Don’t wait for the radiology report.

Look at the images yourself

, and then go and review the images with the radiologist. If you are disciplined about trying to first read the films on your own, your ability to read CTs will improve rapidly.

4

and

5

. Questions #4 and 5 are best answered as part of a general, systematic strategy on how to approach a CT scan, which will be discussed below.

Opening the Images

A. Orientating yourself. Always start reading the abdominal CT from cranial to caudal, and look at the structures from the most anterior to the most posterior, looking at axial or transverse images. Therefore, structures on the left side of the screen are right-sided structures (eg, liver, inferior vena cava), while structures on the right side of the screen are left-sided structures (eg, spleen).

B. Choosing the right “window.” The “window” is the amount of contrast and brightness with which you display the CT image data on the monitor. Most systems have presets such as “abdominal,” “lung,” and “bone” (to name but a few). If you’re looking for free air, the lung window is better. If you need to evaluate the spine or the pelvis (following injury), make sure you choose the bone window. You may look through the images multiple times, each time with a different window.

C. The HU. The HU system is designed to standardize the density reading across different CT machines. By definition, water has 0 HU. Bone has the maximum density among all body tissues (up to 1000 HU). Proteinaceous fluid (including fresh blood) has 20 to 45 HU, and organized hematomas (ie, clots) have 45 to 70 HU.

D. Systematic reading. It does not matter in which order you read an abdominal CT, as long as you always read it in the same systematic fashion. This reduces the chances that you miss something. We suggest the following systematic steps to read an abdominal CT, but one should be free to derive his or her own system for reading images:

i. Check the abdominal wall:

•

Look for any hernias or any irregularities in the abdominal wall.

•

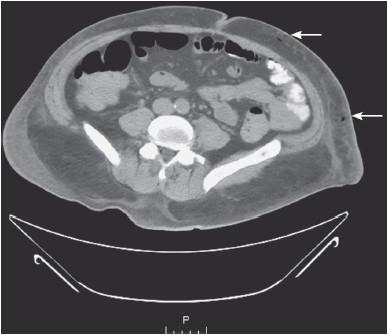

Look for any thickening of the abdominal wall layers or any bubbles of air that could be concerning, in the right clinical scenario, for necrotizing skin and soft tissue infections (see

Figure 56-1

).

Figure 56-1.

CT abdomen revealing abnormal air within the abdominal wall. In the right clinical scenario, this finding is suspicious for a necrotizing skin and soft tissue infection.

ii. Look for free air:

•

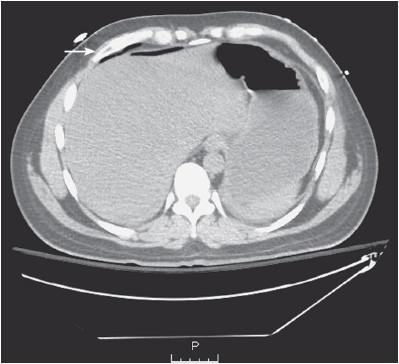

An easy trick is to look for free air using the “lung window” (see

Figure 56-2

).

Figure 56-2.

Quickly looking at the abdominal CT using the lung window helps better visualization of any abnormal free air versus intraluminal air in the peritoneal cavity.

•

Free air can be normal in the immediate postoperative phase (up to 1 week), but is otherwise often an indication for emergent surgical intervention.

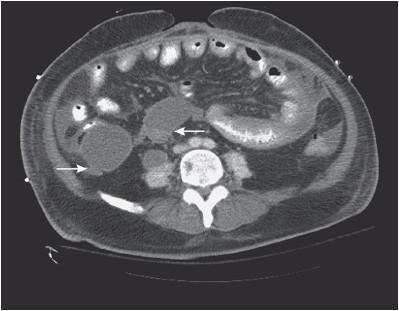

iii. Look for free fluid and intra-abdominal fluid collections:

•

Free fluid in the abdomen is an abnormal finding and can be seen anywhere in the abdominal cavity (see

Figure 56-3

).

Figure 56-3.

Free fluid.

•

It most commonly represents blood, pus, ascites, or enteric contents.

•

An intra-abdominal fluid collection could be a benign/malignant tumor or an intra-abdominal abscess (see

Figure 56-4

).

Figure 56-4.

Two intra-abdominal fluid collections, suspicious for abscesses.

iv. Look for tubes and drains:

•

Follow all Jackson-Pratt, radiology-placed, gastrostomy, nasogastric, and nasoenteric tubes to make sure their intra-abdominal tip positions are where they are supposed to be.

v. Check the liver and biliary tree:

•

Look for any irregularities in the liver parenchyma, or any air in the biliary tree.

•

Look for subcapsular hematomas or liver lacerations in trauma (see

Figure 56-5

), and for liver nodules in a patient with a history of malignancy.