Resident Readiness General Surgery (73 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Figure 56-5.

Splenic laceration caused by a motor vehicle crash.

•

Look for gallbladder thickening or intracholecystic stones or polyps.

vi. Check the spleen:

•

Check for lacerations (eg, trauma), enlargement (malignancy, hyper-splenism), or abnormal fluid collections (eg, liver abscess or cyst) (see

Figure 56-6

).

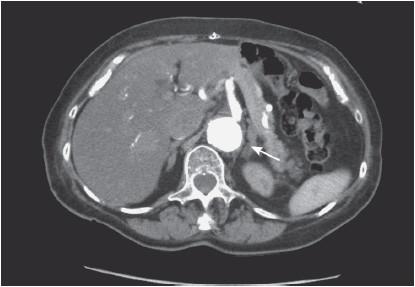

Figure 56-6.

Liver fluid collection suspicious for liver abscess.

vii. Check the pancreas.

viii. Check for tumors, inflammation, ductal dilatation, and/or intraductal stones (see

Figure 56-7

). Check the kidneys for hydronephrosis, lacerations, or pericapsular hematoma (see

Figure 56-8

).

Figure 56-7.

Severe pancreatic inflammation.

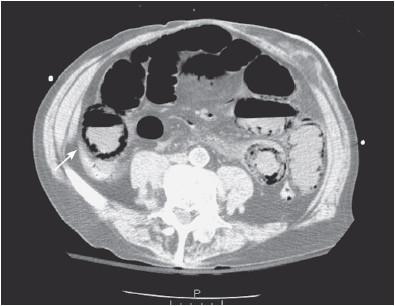

Figure 56-8.

Left kidney hematoma caused by a motor vehicle crash.

ix. Follow the stomach and small bowel:

•

PO contrast allows better definition.

•

Look for “transition points” in suspected bowel obstruction.

•

Look for mesenteric thickening, bowel wall thickening, and/or intestinal pneumatosis (see

Figure 56-9

).

Figure 56-9.

Severe intestinal pneumatosis suggestive of bowel ischemia.

x. Check the colon, appendix, and rectum:

•

Follow the colon.

•

Look for a thickened appendix and for absence of contrast (appendicitis) (see

Figure 56-10

).

Figure 56-10.

Acute appendicitis: note the periappendiceal fat stranding.

•

Look for diverticulosis versus diverticulitis.

•

Look for masses or lymphadenopathy.

xi. Check the aorta and its branches:

•

Follow the aorta from the diaphragm level, identifying sequentially the celiac artery, the superior mesenteric artery, the renal arteries, the inferior mesenteric artery, and the aortic bifurcation (see

Figure 56-11

).

Figure 56-11.

Celiac artery at its origin from the aorta.

•

Look for intraluminal filling defects or abrupt cutoffs, especially when mesenteric ischemia is suspected.

xii. Check the inferior vena cava:

•

Look for filling defects (eg, thrombus).

xiii. Check the pelvic bones and spinal vertebrae:

•

The bone window is helpful for assessing the pelvis and the spine for fractures, especially in the trauma setting.

CONCLUSION

Learning when to order abdominal CTs and how to interpret its images is a skill that you will learn over many years of your surgical training and beyond. However, knowing the basics and developing a systematic way to read a CT are essential tools to maximize your learning, especially in the first few years of residency. Building on the information in this chapter requires continued practice reading the CT images that you should do every time you order this type of study.

COMPREHENSION QUESTION

1.

Which window choice helps you see pneumoperitoneum the best?

A. Lung

B. Abdomen

C. Bone

D. Mediastinum

Answer

1.

A

. If you are looking for free air, in this case in the peritoneum, the lung window is the best choice.

A 60-year-old Man With Postoperative Wound Complications

A 60-year-old Man With Postoperative Wound Complications

Michael W. Wandling, MD and Mamta Swaroop, MD, FACS

Mr. Smith is a 60-year-old man who recently underwent an elective open right hemicolectomy for an adenocarcinoma of the ascending colon. The case and postoperative course were unremarkable and he was discharged home on postoperative day number 4. The following day, however, he called your clinic to report subjective fevers, some increased discomfort around his incision, and new drainage from the wound. You instructed him to come to your clinic.

When he arrives, his vitals signs are T 101.4, HR 92, BP 135/85, RR 15, and O

2

99% on RA. His abdominal exam is significant for a stapled midline laparotomy incision with new-onset erythema that extends approximately 3 to 4 cm laterally and inferiorly from the inferior one third of the wound. A small amount of yellow-tinged thin fluid is coming from between several of the staples. There is also a significant amount of this fluid on the dressing. Palpation reveals mildly increased superficial tenderness surrounding the inferior one third of the wound with no fluctuance or crepitus. There is no rebound tenderness and no guarding. The remainder of the physical exam is normal. You send some blood work, which reveals a white blood cell count of 11,400 cells/mm

3

.

1.

If you know that this patient’s surgical incision was classified as “clean-contaminated,” what is the probability that he would develop a wound infection?

2.

Name two other factors, besides the level of intraoperative contamination, which can modify the risk of surgical site infection (SSI)?

3.

Is this most likely a hematoma, seroma, or wound infection? Why?

4.

Should you order any imaging?

5.

If this turns out to be an infection, should you open the wound?

6.

If this turns out to be a seroma or hematoma, should you open the wound?

7.

What is the most likely pathogen that caused this problem?