Resident Readiness General Surgery (77 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Local anesthetics can lead to toxicity if given in incorrect dosages.

There are several steps that can be used to minimize the pain associated with local anesthetics including mixing in sodium bicarbonate, anxiolytics, and wound pretreatment techniques.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

What is the mechanism of action of local anesthetics?

A. Temporary inhibition of sodium channels along cellular membranes

B. Reduced calcium uptake into the sarcoplasmic reticulum

C. Decreased extracellular magnesium concentrations

D. Depletion of intracellular chloride stores

2.

You are about to suture a very large laceration in a 75-kg man with normal liver function. How much 1% lidocaine can you safely inject without worrying about toxicity?

A. 30 mL

B. 40 mL

C. 50 mL

D. 60 mL

3.

Which of the following skin layers should you be aiming for when injecting local anesthetic?

A. Epidermis.

B. Dermis.

C. Subcutaneous tissue.

D. All skin layers should be anesthetized.

Answers

1.

A

. Local anesthetics act by reversibly blocking nerve impulses by disrupting cell membrane permeability to sodium during an action potential.

2.

A

. For an average patient with no hepatic impairment, up to 4.5 mg/kg of lidocaine can be given during the procedure. Therefore, this patient can receive around 330 mg of lidocaine total. A 1% concentration of lidocaine has a concentration of 10 mg/mL so this patient can receive around 30 mL without worrying about toxicity.

3.

B

. When injecting local anesthetics, the goal is to inject the local anesthetic into the deep dermis to block the sensory plexus.

A 52-year-old Woman With a Suspected Congenital Coagulopathy

A 52-year-old Woman With a Suspected Congenital Coagulopathy

Jahan Mohebali, MD

Ms. Smith is a 52-year-old female who presents to your office for a possible laparoscopic sigmoid colectomy. She states that she has no significant medical history other than diverticulitis. Her only previous surgery was a wisdom tooth extraction at the age of 21. She notes that the procedure was uneventful; however, she continued to have significant oozing from her gums for approximately 24 hours. On review of systems, she notes that she has always bruised quite easily as long as she can remember. Further questioning reveals that she may have also had menorrhagia, although this was never formally diagnosed. Her laboratory data reveal a normal complete blood count. Her coagulation panel is notable for a mildly elevated partial thromboplastin time (PTT) and a prolonged bleeding time.

1.

What is the single best predictor of an inherited disorder of coagulation?

2.

What are the two major categories of coagulation abnormalities and what symptoms are associated with each?

3.

What is the standard workup when an inherited coagulopathy is suspected?

4.

Which laboratory tests will distinguish a platelet disorder from a problem with coagulation factors?

CONGENITAL COAGULOPATHY

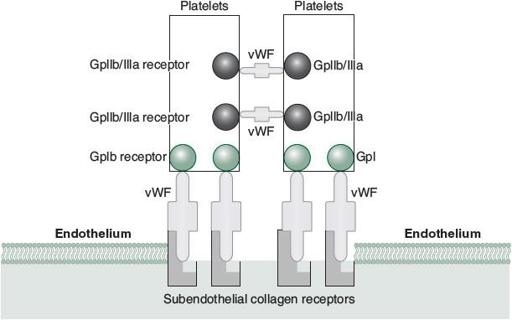

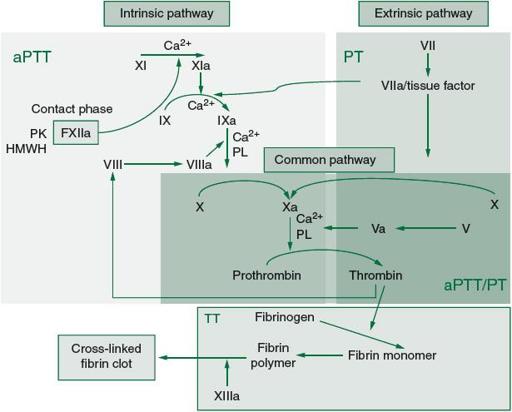

In order to understand congenital coagulation disorders, one must begin by briefly reviewing the steps of normal hemostasis (see

Figure 59-1

). Although it is not essential to memorize every step of the cascade, one must understand that there is an intrinsic pathway that is initiated by exposure of blood to collagen as may happen with endothelial damage and an extrinsic pathway that is initiated with exposure to tissue factor. These pathways converge with the activation of factor X and formation of the tenase complex, which initiates the final common pathway by converting prothrombin to thrombin, and finally fibrinogen to fibrin. It is also important to note that platelets not only are involved in forming the initial hemostatic plug but also serve as the surface on which the tenase complex assembles.

Figure 59-1.

Coagulation cascade and laboratory assessment of clotting factor deficiency. (Reproduced, with permission, from Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Loscalzo J.

Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine

. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2012. Figure 116.1. <

www.accessmedicine.com

>. Copyright © The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc. All rights reserved.)

Answers

1.

The single best predictor is the preoperative history and physical exam. Careful history taking is usually more revealing than preoperative coagulation studies.

The preoperative hematologic history should focus on whether or not the patient has ever experienced a previous episode of abnormal bleeding. If the

patient has had a previous operation, he or she should be questioned regarding any complications related to bleeding or poor hemostasis intraoperatively or in the postoperative period. If the patient has not undergone a previous surgical procedure, the history should focus on prolonged or abnormal bleeding related to trauma, previous episodes of mucosal bleeding or epistaxis, a history of menorrhagia in women, extensive bleeding after dental procedures, or a history of subcutaneous, intramuscular, or intra-articular hemorrhage.

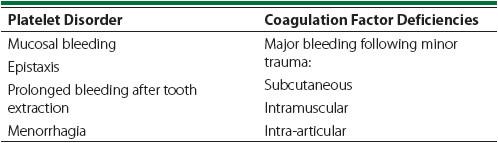

2.

Most congenital coagulopathies are the result of an abnormality related to platelets, to coagulation factors, or, occasionally, to both. Whenever a disorder of hemostasis is suspected, an attempt should be made to determine which of these is the culprit. Bleeding related to thrombocytopenia or decreased platelet function is typically manifested as mucosal bleeding, epistaxis, prolonged bleeding after tooth extraction, and menorrhagia (in women). Bleeding as a result of coagulation factor abnormalities is more likely to present as major

subcutaneous, intramuscular, and, classically, intra-articular hemorrhage following minor trauma (see

Table 59-1

).

Table 59-1.

Comparison of Signs Associated With Each Type of Coagulation Disorder

Platelet disorders

The most commonly encountered inherited coagulopathy is von Willebrand disease (vWD). This disorder should be thought of as a functional platelet disorder. The prevalence of vWD has been reported to be as high as 1 in 100 in some populations. The second and third most commonly encountered hereditary coagulopathies are factor VIII deficiency resulting in hemophilia A with a prevalence of roughly 1 in 10,000 and factor IX deficiency resulting in hemophilia B with a prevalence of roughly 1 in 100,000.

von Willebrand factor (vWF) is a multimeric protein contained within vascular endothelial cells and in plasma that facilitates the binding of platelets to subendothelial collagen through Gp1b receptors. It also serves as a stabilizer of factor VIII, which is why patients with vWD may also have some degree of factor VIII deficiency. As previously mentioned, because vWD is a functional platelet disorder, these patients will typically have a history of mucosal bleeding, significant bleeding after dental procedures, epistaxis, and menorrhagia (in women). In fact, patients with the most severe form (type 3) may actually suffer from hemarthroses because of their factor VIII deficiency.

Other less common congenital platelet disorders may include thrombocytopenia from splenic sequestration as a result of a multitude of congenital storage and hematopoietic disorders, and other functional platelet disorders. Glanzmann thrombasthenia and Bernard-Soulier syndrome are two other inherited functional platelet disorders that result in bleeding despite a normal platelet count (see

Figure 59-2

).