Resident Readiness General Surgery (37 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Aortic dissection

: The textbooks state that this presents as intrascapular back pain, but it can present as anterior chest/shoulder pain. The key is that it really hurts. Typically these patients are hypertensive, and urgent therapy includes aggressive blood pressure control. It is important to distinguish

between ascending dissections (requires surgical intervention with a pump) and descending dissections (can be tucked away in your ICU with a

right

radial arterial line and intravenous antihypertensive drugs). This distinction can usually be made with a TTE or CT angiogram.

Reflux esophagitis

: This is surprisingly common in the perioperative period, but it’s OK if you miss it. Give an antacid.

Leaking triple A

: This can be tricky because the stakes are high. Traditionally, when a previously hypertensive, elderly male presents with acute low back pain, the diagnosis is a “leaking triple A.” If this patient is hypotensive, he should be taken directly to the operating room. A rapid ultrasound of the abdomen can be very reassuring.

Do obtain a 12-lead ECG.

If this patient is really having an acute MI, a midline abdominal incision will likely prove lethal.

Costochondritis

: A diagnosis of exclusion, and it’s OK if you miss it. Give antiinflammatory Rx.

Acute cholecystitis

: It seems unfair that this can masquerade as chest pain. In a fair/fat/fortyish female, it is more likely than myocardial ischemia. Obtain a RUQ ultrasound.

Pneumonia

: This typically doesn’t hurt unless the inflammation extends out to the exquisitely sensitive pleura—then it can hurt a lot. A chest x-ray should confirm the diagnosis.

Tension pneumothorax

: This also usually doesn’t hurt and presents as hypotension and tachycardia because the increased intrathoracic pressure decreases venous return—paradoxically, it is a volume problem (not respiratory). Do not wait for a chest x-ray. Obtain vital signs and listen to both sides.

Pneumothorax

: Perhaps surprisingly, this can be completely painless. Unless this patient is hemodynamically unstable, there is no urgency. Confirm diagnosis with a chest x-ray.

Cardiac tamponade

: This is a very rare cause of acute chest pain. The diagnostic and therapeutic urgency depends entirely on the hemodynamic status of the patient.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

You can avoid unnecessary delay by initiating both treatment and the diagnostic workup prior to arriving at the bedside.

Acute MI is both common and serious, but you must also not miss PE, aortic dissection, leaking AAA, tension pneumothorax, and cardiac tamponade.

COMPREHENSION QUESTION

1.

Which of the following should

not

be ordered over the phone, before you have seen the patient?

A. Sublingual nitroglycerin

B. EKG

C. CXR

D. Oxygen

Answer

1.

A

. While nitroglycerin is indicated if there is evidence of myocardial ischemia, you don’t yet know the diagnosis. In that case, nitroglycerin can actually make things worse—for example, in a patient with a tension pneumothorax.

A 65-year-old Woman With a New-onset Cardiac Arrhythmia

A 65-year-old Woman With a New-onset Cardiac Arrhythmia

Alden H. Harken, MD

A 65-year-old female arrived in the postanesthesia care unit (PACU) 30 minutes ago following a sigmoid resection for adenocarcinoma. The operation went well, and there was minimal blood loss. She was extubated in the operating room. Blood pressure on arrival in the PACU was 130/80 with a heart rate of 90. Several minutes ago, her heart rate abruptly increased to 160 and her BP dropped to 90/60 mm Hg.

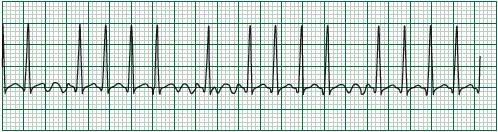

The nurse calls you, and when you arrive, you see a rhythm strip (see

Figure 28-1

):

Figure 28-1.

Rhythm strip of 65-year-old woman in the case above.

1.

What is the most likely reason this patient is now hypotensive?

2.

Is this patient hemodynamically unstable?

3.

If you determine she is unstable, where would you place the pads for cardio-version?

4.

How do you localize the anatomic origin of the dysrhythmia (ie, atrial or ventricular)?

5.

Assume that, as in this case, the patient has atrial fibrillation (AF). What dose of what medication would you give to slow the heart rate?

6.

What can you do to help prevent arrhythmias from occurring or recurring?

SUPRAVENTRICULAR DYSRHYTHMIAS

Answers

1.

The patient’s current problem is a tachycardia. As we get older, our hearts become less compliant (stiffer) and therefore take more time to fill during diastole. This woman’s left ventricle is not adequately filling during diastole, so her stroke volume is reduced and her cardiac output is down. This in turn results in hypotension.

2.

This is a trick question because you don’t have enough information. You must assess whether this patient is adequately perfusing her brain and heart (the only two organs that matter acutely). If the patient is diaphoretic and confused (ie, unstable) and she has a tachyarrythmia (eg, AF, ventricular tachycardia [VT], or ventricular fibrillation [VF]), proceed directly with external cardioversion. If the patient appears to be comfortable and you don’t think that you need to shock her, examine the ECG rhythm strip more closely to try and determine the anatomic origin of the dysrhythmia.

3.

Place one cardioversion paddle on in the right parasternal second intercostal space and the other in the posterior axillary line at the costal margin. If you want to be kind, you may push 20 mg etomidate IV for preshock anesthesia. Set the defibrillator on “sync” and 100 J and press the button. Keep pressing the button for 4 to 5 seconds. Remember that it will take the “quick-look” paddles four to five seconds to “time out” the rhythm so that it doesn’t deliver the shock during the upstroke of the T wave and induce VF.

4.

If the patient is stable, then examine the ECG rhythm strip and look at the width of the QRS. If the QRS is narrow (as in this case), the origin of the dysrhythmia must be supraventricular (above the AV node).

5.

You can give drugs according to how long you want the A-V block to last. See

Table 28-1

.

Table 28-1.

Drugs Used to Slow the Heart Rate (A-V Blockade) and Their Length of Action

Remember, always give drugs intravenously to a hemodynamically unstable patient. Oral medications exhibit unpredictable absorption in a hypoperfused stomach. When a patient is in shock, a pill can rattle around in the stomach for hours.

6.

Fluid and electrolyte shifts coupled with autonomic nervous system stressors conspire to make early postoperative cardiac dysrhythmias relatively common.

After you have blocked the A-V node and the patient is stable again, you can do five things to make dysrhythmia recurrence less likely:

1.

Check blood gases and provide face mask oxygen.

2.

Check serum potassium and keep it above 4.0 mEq/L.

3.

Check serum magnesium and keep it above 2.0 mEq/L.

4.

Check the patient’s prior medicines. Digoxin will block the A-V node, but makes the heart more excitable. Therefore, dysrhythmias are

more

likely, but less of a problem if they occur.

5.

Pain stimulates the adrenals to produce catecholamines that cause dysrhythmias. Morphine 2 to 4 mg IV is a great antidysrhythmic drug.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

If a patient is tachycardic and hemodynamically unstable, cardiovert.