Resident Readiness General Surgery (41 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

3.

Let’s pretend you are stat paged to the cath lab where your cardiology colleagues have placed some stiff catheters into the right ventricle of a middle-aged man. The patient is under the sheets, and the only history you get is that the monitor reveals a heart rate of 120 and he abruptly lost his blood pressure. The cardiac silhouette has not gotten any bigger during fluoroscopy.

After ensuring that the patient’s airway is patent and that the patient is breathing (A and B), you should perform a pericardiocentesis. This is performed by inserting a long #18 (spinal) needle immediately below the xiphoid while aiming for the patient’s left shoulder. If you get air, pull back and try again a little more medially. (If you are in the OR and already in the abdomen, you may more easily access the pleural and pericardial spaces directly across the diaphragm.) If you obtain blood, remove about 20 mL and squirt some on the sheets. If the blood clots on the sheets, you are in the right ventricle. If the blood does not clot, it represents defibrinated blood that was in the pericardial space.

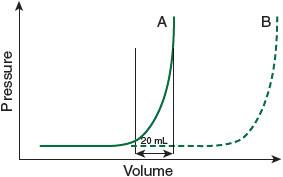

Removing only 20 mL should make a huge hemodynamic difference (see

Figure 32-1

). Conceptually, let’s take some impermissible physiological leaps: by removing 20 mL of pericardial fluid, you permit an additional 20 mL of ventricular end-diastolic filling. The augmented left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) translates into 20 mL of additional stroke volume. An additional 20 mL SV × heart rate of 100 equals an increased cardiac output of 2 L! The good news is that you have helped your patient a lot. The bad news is your patient only needs to reaccumulate another 20 mL in order to get back into trouble.

Figure 32-1.

The pressure in the pericardial space remains low with increasing volume until the elastic limits of the pericardium are attained, at which point the pressure soars (A). Note that only a 20 mL volume difference produces a big increase in pressure at the elastic limit. A chronic pericardial effusion (B), however, can stretch gradually, with negligible increase in pressure.

4.

In this scenario, let’s pretend that the patient is a young, healthy-appearing biker who has rolled his bike at high speed on the interstate. Your crack paramedic team rings down: “No vitals in the field” on arrival in the ED. There is a big diagnostic fork in the road.

Fork A: The nurses slap on EKG leads, indicating a sinus tachycardia of 140 and no BP (PEA). On fast exam there is minimal or no ventricular motion. You should “call the code.” A massive amount of epidemiological data confirms negligible “walkout of the hospital” survival following “blunt trauma with no vitals in the field.”

Fork B: The fast exam reveals vigorous ventricular contractility and a belly full of blood. You should activate the massive transfusion protocol on the way to the operating room.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

When you are stat paged, your destination determines your differential diagnosis. The most likely problems differ when you are called to the ED, the OR, the cath lab, or the dialysis unit.

The three most common causes of PEA are hypovolemia, tension pneumothorax, and cardiac tamponade. All three respond to volume.

The diagnosis of tamponade is not made by x-ray or ultrasound. Tamponade is not an “imaging” diagnosis.

A “pericardial effusion” becomes “pericardial tamponade” when the patient can no longer compensate in order to maintain ventricular filling. Eventually such patients go into PEA arrest.

Similarly, a “spontaneous pneumothorax” becomes a “tension pneumothorax” when the patient can no longer compensate, venous return falls, and once again the patient cannot maintain ventricular filling.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

You are in the OR performing an open procedure when your patient goes into PEA arrest. The first thing you should do is which of the following?

A. Obtain a rhythm strip.

B. Decompress the bilateral chest through the diaphragm.

C. Obtain a CXR.

D. Check the ET tube position.

2.

You are in the OR performing a laparoscopic procedure when your patient goes into PEA arrest. You decide to decompress the chest. You should place a #18 needle in which of the following positions?

A. In the midaxillary line above the nipples

B. In the midclavicular line as close to the clavicle as possible

C. Through the diaphragm

Answers

1.

D

. ABC—airway comes first.

2.

A

. The diaphragm can be surprisingly high when a patient is supine—and especially when the abdomen is insufflated for a laparoscopic procedure. Don’t place the needle in the midclavicular line as there is a risk of hitting the subclavian.

A 55-year-old Man Who May Require Perioperative β-blockade

A 55-year-old Man Who May Require Perioperative β-blockade

Alden H. Harken, MD

and Brian C. George, MD

A 55-year-old banker is driving back to work following a three-martini lunch when he is T-boned by a cement truck. On arrival in the emergency department he is hemodynamically stable and alert. He prides himself on never having graced a physician’s office and he is on no medications. FAST exam reveals fluid in the LUQ. During the next hour his blood pressure drifts down and you are forced to take him to the OR for a splenorrhaphy.

You are writing his postoperative orders using a template, and you arrive at the section with numerous possible options for postoperative β-blockade. As you write your postoperative orders, you wonder: “Should I put this guy on a β-blocker?”

1.

Should you put this patient on a β-blocker?

2.

If he instead took metoprolol 25 mg PO twice a day at home, what dose would you give him of IV metoprolol while he is NPO?

PERIOPERATIVE β-BLOCKADE

Answers

1.

In 1999, Poldermans et al screened almost 800 high-risk vascular patients with dobutamine stress echocardiography. These investigations then culled approximately 200 very, very high-risk vascular patients formidably vulnerable to myocardial ischemia from the original high-risk group. Two weeks of β-blockade prior to the vascular surgical procedure cut the mortality from 34% (control) to 3.4% (β-blockers)—a huge difference.

However, is it permissible to extrapolate from this very, very high-risk vascular surgical group to just high-risk or even moderate-risk patients? Mangano previously stoked the confusion by prospectively randomizing 200 surgical patients into β-blocker and placebo groups. The 30-day mortality was the same, but 2-year mortality statistically favored β-blockade. Taken together, it began to look like preoperative β-blockers were certainly good for very high-risk patients, probably benefited moderate-risk patients, and might be good for everyone. Extending the tenets of a great American philosopher (Mae West opined that “Too much of a good thing is wonderful”) the PeriOperative ISchemic Evaluation (POISE) trial gave up to eight times the recommended dose of extended-release β-blockers to any patient with a heart rate over 60. In this huge study of 8351 patients in 23 countries (they could not talk any US investigators into participating), there

was a reduction in myocardial infarction (5.7%-4.2%;

P

<.0017), but β-blocked patients with heart rates of 60 induced more strokes (0.5%-1.0%) and more deaths (2.3%-3.1%;

P

<.03). The investigators did not report whether they were surprised by the results of their pharmacological experiment.