Resident Readiness General Surgery (19 page)

Read Resident Readiness General Surgery Online

Authors: Debra Klamen,Brian George,Alden Harken,Debra Darosa

Tags: #Medical, #Surgery, #General, #Test Preparation & Review

Figure 14-1.

(

A

) Supine KUBs with dilated loops of small bowel. (Reproduced with permission from Zinner MJ, Ashley SW.

Maingot’s Abdominal Operations

. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007 [Figure 17-9].) (

B

) Upright KUB with multiple air–fluid levels (arrows). (Reproduced with permission from Zinner MJ, Ashley SW.

Maingot’s Abdominal Operations

. 11th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2007 [Figure 17-9].)

Though more time-consuming, a CT of the abdomen and pelvis is the most sensitive diagnostic tool. This study, unlike a KUB, can provide information about the precise location, severity, and etiology of the obstruction. Often times a transition point (a change in caliber between dilated proximal and collapsed distal small bowel loops) can be identified.

3.

The biggest challenge in treating an SBO is knowing when to take a patient to the operating room. The real danger of an SBO comes from bowel that has dilated or twisted to the point where its blood supply has been compromised. This can lead to necrosis, perforation, and sepsis. Patients with severe abdominal pain, no prior history of abdominal surgery, or those suspected to have a closed loop obstruction should undergo prompt laparotomy. Unfortunately, most patients fall into more of a gray area and neither physical examination nor CT scan is very accurate in predicting the need for an operation. In these patients, watchful waiting with serial abdominal examinations is an acceptable choice. Increasing abdominal pain or persistent obstruction after 24 to 48 hours is a commonly accepted indication for surgery.

4.

In a patient with a suspected SBO, an NGT is almost always warranted. An NGT can be both therapeutic and prophylactic. By emptying the GI system, it allows the bowel to decompress, edema to resolve, and, if the obstruction is partial, the bowel to “open up.” It is prophylactic in the sense that it drains the stomach and prevents aspiration of vomitus. This is especially important in elderly or altered patients. The only patients who might not need an NGT are those who have only minimal vomiting and are otherwise healthy enough to protect their airways.

If you are on the fence about placing an NGT, you can order a plain film KUB. Dilated bowel or stomach suggests that an NGT would be helpful. Though unpleasant, it is always safer to put one in than have the patient aspirate in the CT scanner.

Placement of an NGT is contraindicated in patients with a suspected basilar skull fracture, severe oropharyngeal trauma, and recent esophageal or gastric surgery.

5.

To place an NGT, you will need:

14 to 18 Fr NGT (bigger is less susceptible to clogging)

Water-based lubricant

Tape to secure tube

Foley tip syringe

Safety pin to attach tube to gown

For an awake patient, you should also include:

Topical anesthetic jelly or spray

Cup of water with a straw

With an awake patient, it is imperative that you enlist his participation in placing an NGT. Sit the patient upright and have him extend his head like he is sniffing something in front of him. Measure out the length of the tube you plan to insert by holding the tip of the tube at the xyphoid process and wrapping the tube around the back of the ear and then out to the nostril. Next, explain the procedure thoroughly while you inject topical anesthetic jelly into the nares or spray topical anesthetic into the posterior oropharynx. Topical anesthesia should be administered at least 5 minutes before the start of the procedure.

The insertion takes 2 steps. The first part is placing the NGT in the nasal cavity and advancing it to the back of the oropharynx. Make sure you are inserting the tube into the nostril at a 90° angle to the plane of the face and are not aiming it cranially (see

Figure 14-2

). The anatomy of the nasopharynx is such that the tube makes a 90° turn as it enters the oropharynx. This first part feels like getting punched in the nose.

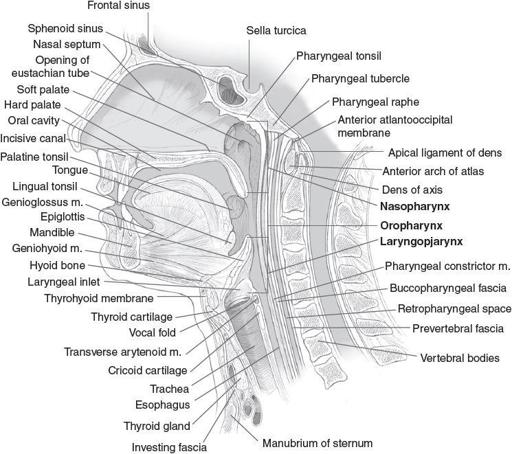

Figure 14-2.

Anatomy of the nasopharynx. (Reproduced with permission from Lalwani AK.

Current Diagnosis & Treatment in Otolaryngology—Head & Neck Surgery

. 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012 [Figure 1-15].)

It is extremely helpful to stop at this point, reassure the patient, and then have him drink some water. This enlists the muscles of deglutition to help advance the tube into the esophagus. As the patient drinks, advance the tube

until you reach your premeasured distance. If the patient starts coughing, you should immediately withdraw the tube back into the oropharynx as you are most likely advancing the tube through the larynx and into the trachea.

Once the tube is in place, tape it securely to the nose. A butterfly bandage (or tape on each side of the nose) that then coils around the NG tube is a typical approach. Secure the tube to the gown with tape and a safety pin so that any tension on the tube will result in pulling of the gown and not the material securing the tube to the nose. Be sure to leave enough slack in the tube so the patient can move his head without dislodging the tube, but not so much that a long loop will get pulled out accidentally.

How to confirm that the tube is in the stomach:

1.

Have the patient say “Hello.” If the patient is unable to speak, the tube is likely in the trachea and should be withdrawn. Note that this technique can also be used as you are advancing the tube, for similar reasons.

2.

Aspirate with the Foley-tipped syringe. Aspiration of gastric contents suggests the tube is in the correct place.

3.

Again using the Foley-tipped syringe, instill 20 cm

3

of air forcefully into the tube while auscultating in the left upper quadrant. You should hear a “burp” of air over the stomach.

4.

Ideal tube positioning should be confirmed with a plain x-ray.

Never instill anything other than air until you are sure the tip of the tube is in the stomach.

6.

Patients presenting with an SBO are usually dehydrated due to the edematous bowel losing its normal absorptive function. This, coupled with vomiting, can lead to severe volume depletion with associated electrolyte derangement. Key to both preoperative and nonoperative treatments is adequate fluid resuscitation and electrolyte replacement. A Foley catheter should, in all but the most robust patients, be placed to monitor urine output and subsequent resuscitation.

Following initial resuscitation, a trick for patients with a suspected

partial

SBO is the administration of water-soluble contrast. The hypertonic solution draws fluid into the lumen and theoretically reduces edema. In a number of trials, water-soluble contrast was found to reduce the need for operative intervention.

TIPS TO REMEMBER

SBO patients are usually hypovolemic and in need of resuscitation—placing a Foley catheter and following the urine output can help guide you.

SBO patients who do not require immediate surgery should be watched very closely for signs of bowel ischemia.

Always have an awake patient help you by swallowing during placement of an NGT.

Never instill anything in an NGT until you are sure it is in the stomach.

COMPREHENSION QUESTIONS

1.

Which of the following is

not

something you should specifically look for on physical examination in a patient you suspect of having an SBO?

A. Rovsing sign (palpation of the left lower quadrant resulting in increased pain in the right lower quadrant)

B. Abdominal tenderness to palpation

C. Inguinal or ventral hernia

D. Abdominal surgical scars

2.

Which of the following warrants immediate surgical exploration?

A. Patient who has been vomiting for 24 hours

B. A patient with dilated loops of small bowel on KUB

C. A patient with a closed loop obstruction on CT scan

D. A patient with NGT output of 200 cm

3

/h

3.

You attempt to place an NGT and think you hear a puff near the stomach when you instill 20 cm

3

of air. What’s next?

A. Place the NGT on suction and go write orders.