Resurrection Man (13 page)

"And warn them off the damn things if it doesn't," he'd grumbled, but the argument had been good enough. (And as Mother tartly observed, it hadn't hurt that Radetzky himself was Hungarian on his father's side.)

Ruminatively Dr. Ratkay pulled a fingerful of shredded tobacco from the pouch of Amphora. "Things change in medicine, of course, but not the central thing." Dante raised his eyebrows. "People die," his father answered, with a small rueful smile.

Dante shelved the Book, feeling a stab of pain from his abdomen, like a bad stitch. "I guess they do."

Dr. Ratkay frowned at the pipe mug, puzzled. "Hum. I wonder what happened to—"

Hastily Dante pulled the lure from his shirt pocket. "I took it out yesterday, to fish. I was just going to put it back."

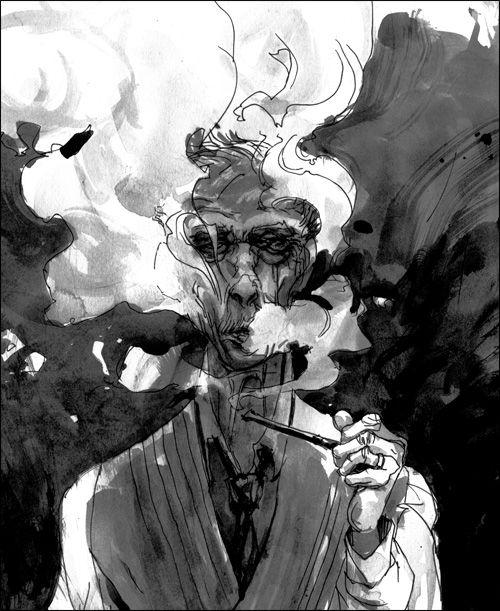

Dr. Ratkay's eyebrows rose. "Quite a catch you made with it, too. That ring." He tamped down his wad of tobacco and struck a match. Shredded leaves flamed, blackened, burned. He sucked pleasurably and exhaled a cloud of blue-gray smoke.

Dante couldn't help grinning. I should get him a Chinese lounging robe, he thought. He would make a perfect scholar-dragon, a gently steaming mandarin lazing amid his hoard of books. Behind the smoke those eyes, still as bright as blue sky in winter.

His father examined him. "You know," he began, releasing the pipe with a small pop and a puff of smoke, "you are the same age now I was when you were born."

They pondered this in silence for a moment, Dante standing awkwardly with his hands in his pockets, his father seated, with his legs crossed and two fingers over the black briarwood bowl of his pipe. "I guess I don't measure up," Dante said lightly. "No wife, no kid, no degree. Hardly a job."

"True," his father conceded with a smile, "but not what I was thinking."

"Enlighten me."

Dr. Ratkay drew on his pipe. He blew a long slow stream of smoke into the air. Where it crossed the sunlight falling through the narrow window, it shone.

"When you have a child," he said at last, "it brings a lot of grief." He held up a hand. "Not the child's fault: at the worst the child brings exhaustion, bad temper... dry-cleaning bills." He shot a glance at Dante, reliving a distant memory. Thoughtfully Dr. Ratkay rubbed his chin. "'Fathers are children for the second time,' as Aristophanes almost said. When you have a child, you see in him yourself as a child. That's part of what you love in him, you see. You love yourself, your younger self. And when you look at him and worry, you do it because you think of all the things you lost, growing up. All the hurt... " He stopped himself, blinked and smiled. "So now, looking at you, you fine, tall, smart young man, I can see all the mistakes I'm going to make with you and your siblings, and your aunt, and my practice, and God knows your mother."

"You? Make mistakes? I thought it was impossible!"

Anton smiled. "I did too, at your age. That was pretty old to be so foolish!"

"Whereas I know I hardly ever do anything right," Dante said. "I must be exceedingly wise."

Anton shook his head, looking sadly at his son through a haze of blue smoke. After a long silence, he said, "No. You're an even bigger fool than I was."

* * *

"Dad seemed a little glum tonight," Sarah remarked to her mother after dinner that evening.

Mother shrugged. Sleeves rolled up to her elbows, she pulled the last few scraps of meat off the turkey's ribs and tossed its skeleton in the garbage. Beside her, Sarah sighed and pulled on an apron, looking over the usual wreckage of dishes Saturday dinner had left in its wake.

"I've never seen your brother carve with such a... scientific interest," Mother remarked.

Sarah started water running in the sink and added a healthy shot of detergent. Aunt Sophie had a deep aversion to dishwashers, which was fine, but as she had retired to her room after dinner, feeling unwell, it left Sarah with a depressing collection to do by hand. "We ought to get the boys in here to help."

Mother laughed. "Jet and Dante did most of the cooking while you snoozed upstairs this afternoon, you lazy thing."

"Yeah, I know." Resigning herself to the inevitable, Sarah rolled up her sleeves and began to scrub. She still felt hungry, but her reflection in the kitchen window told her she had eaten too much.

She hated it.

It was dark now. The lowering clouds had finally made good on their promise; rain creaked and spattered on the kitchen window, running in sudden tear-tracks down the glass. Sarah felt dull and melancholy. Two hours of fitful sleep, snatched in the mid-afternoon, had not made up for the horrors of last night's autopsy. Even Saturday dinner had been subdued: Aunt Sophie grim and moody, Father terse and withdrawn.

Mother clinked and clattered about the kitchen, determinedly cheerful. "When's your next show?"

"Tuesday night at Yuk-Yuks." As Sarah reached to fish another greasy plate out of the dishwater, her eyes involuntarily jumped to the window. Something had moved.

Something had moved outside.

She squinted, trying to see into the rainy night, but it was bright in the kitchen, and the window was crowded with reflections.

Once, years before at a darker time in her life, she had lain in bed in an apartment downtown, listening to the sound of faint screaming, very far away; it had run down her skin in tiny tracks of fear, like cold water. Tonight, straining to see through her own reflection, she felt the same fear sliding coldly down her face.

She leaned forward until her forehead touched the glass, looking through her own reflected eyes. Her heart was racing. Yes—there! Down at the bottom of the wilted garden, not far from the dim bulk of the boathouse.

Wasn't there a child, a little girl, staring up at the lighted window?

Staring in at the warm house from the cold and the rain; a child in jeans and a white T-shirt. A scrap of a girl with water dripping from the brim of a baseball cap.

With a little cry Sarah dropped the plate she had been washing. It smashed as she leapt to the back door, pulled it open, banged through the screen door and ran down the porch steps.

Outside the air was huge and full of night. Sarah faltered and stopped. Cold drops of rain spattered against her face.

Nothing. No one.

She took a few halting steps down through the garden. No one waited for her there. No sad little face reproached her from the shadows beneath the boathouse eaves.

The wind sighed around, her, and the rain wept. Still Sarah walked, heart pounding and pounding in her chest. She did not let herself think. This was not a time for questions. She could only run; into the night, or away from it. Those were her choices. She had made the wrong choice once, eight years before. She knew she couldn't bear to live if she made the wrong choice again.

The clouds stretched on forever; the thin breeze gusted and fell. Down beyond the slowly creaking dock, the dark river rolled on.

"Sarah? Honey—are you all right?"

Her mother stood in the doorway, calling to her. Warm yellow kitchen light spilled across the porch, and it was Sarah, Sarah who now stood, forlorn, in the shadow of the boathouse. From here the house looked unimaginably remote, warm and friendly and utterly inaccessible, having nothing to do with the rain whispering off into eternity around her. Nothing to do with the river, and the rolling darkness that covered everything real.

Soaked and shivering, Sarah watched her mother pick her way down through the garden. "A rabbi, a Baptist preacher, and a Roman Catholic priest are out walking one day when they meet the angel Gabriel," Mrs. Ratkay said, as soon as she was close enough for Sarah to hear.

"The rabbi says, 'Oy! Just who I wanted to see! I have here a list of complaints for you to take to the Master of the Universe.' And he takes out a book about a thousand pages long and gives it to Gabriel, and Gabriel says, 'As you wish.'

"Then the preacher says, 'Hallelujah! Praise be! I need you to take this petition singing the praises of Christ Almighty down to Hell. We're going to shame the devil! As you can see, it's been signed by over a million viewers—uh, that is, members of the congregation.' And he too takes out a book about a thousand pages long, covered in signatures. And Gabriel says, 'Very well.'

Mrs. Ratkay put her arm through her daughter's arm and began to lead her gently up toward the house. "Well, that leaves the priest, who's looking kind of embarrassed. He hems and haws for a while, and shuffles his feet, and runs a finger around his clerical collar, and finally mumbles, 'Thanks for coming,' and stuffs a tiny slip of paper into Gabriel's hand. The angel picks it up and reads it, and a sudden change comes over him. His teeth start to chatter and his knees begin to knock. 'You're crazy!' he says, and dropping the slip of paper he flies shrieking into the night.

"Well, of course the rabbi and the preacher are amazed," Mother continued, guiding Sarah up the porch steps. "They stare at the priest so hard, he finally grins a feeble grin and says, 'A letter from me to the Pope, asking if we could ordain women.'"

Sarah almost smiled. "—And then the rabbi and the preacher also fly shrieking into the night," she whispered.

Gwen Ratkay led her daughter into the kitchen and sat her at the table while she put on a kettle. She took Sarah's hand. "Are you okay? I see little teapots behind your eyes, brewing tears."

Sarah couldn't laugh. It was too dark outside, too dark and cold; and the sad rain dripped and crept over all the earth. "Eight," she whispered.

Gwendolyn's eyes closed, her shoulders sagged, and for a brief moment she looked very old. "Shh," she murmured, softly stroking her daughter's hand. "It's okay, sweetheart. It's okay."

Sarah shook her head, furious. "She would have been eight years old," she cried. And wept and wept.

* * *

In the kitchen, Sarah cried while her mother gave her what comfort she could. In his study, Dr. Ratkay smoked and, sighing, painted a charm for the Gregson girl, who was young enough to hope it might somehow cure her baby's leukemia. Upstairs, Aunt Sophie bent over her sewing table, studying a pattern of coins with an expression both wondering and resentful, unable to believe what she saw prophesied in their fall.

Jet and Dante were talking softly in the parlor, where Grandfather Clock wove his steady, ceaseless spells against the dark night and the spattering rain. Red light flickered in his glass heart from the fire that hissed and creaked on the hearth. Dante jabbed moodily at the fire with a brass poker. It blazed and burned. Hungry flames caught; held; flowed in blue streams up the pale sides of the naked wood. Little red tongues licked black streaks onto it, burning it up, burning it away, burning it down into embers and ashes.

"What are you thinking?" Jet asked.

Dante blinked and shook his head. "Nothing. Everything." The bones of the human hand; Jet carefully rolling up the bamboo walls of their fort and storing them in the boathouse; the willow tree, its welts gummed with sap; dirt falling by the shovelful over his own face; the white sac webbed around his kidney and liver.

Maple leaves, burning down into winter.

"Someone broke into my apartment last night, you know. Laura called." Wearily Dante rubbed his eyes. "The cops think the guy was looking for something."