Resurrection Man (17 page)

* * *

Marry me?

M

AN, LIKE A LIGHT IN THE NIGHT, IS KINDLED AND PUT OUT.

—H

ERACLITUS

CHAPTER

NINE

Portrait

This picture was crucial to my career. As the winning photo in a juried competition, it opened the way for me to get steady work as a freelancer for the City's two big newspapers. To my certain knowledge it also cost one man his life.

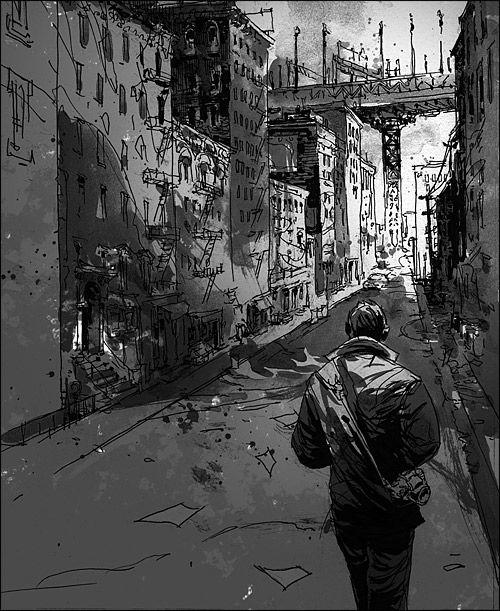

I spend a lot of nights away from home, walking through the city, seeing it in black & white. By day it is noisy, crowded, absurd with its seething millions. At night, against a stark black background, stories play out cleaner, and the great features of the city shadow forth: downtown with its continents and canyons; the river a ribbon of woods threaded through the City's heart, where tramps live in cardboard boxes or under plastic bags strung from trees. Westwood like a garden, its houses planted in stately rows, Volvos sprouting from each driveway. Peter Street and The Scrubs: desolations of asphalt and broken glass.

There is a class of walkers who share a certain camaraderie. We are not drunks, tramps, hookers, cops, priests, party-goers or night-shift workers: we are merely outsiders. On the rare occasions when we meet we acknowledge one another with a tiny tilt of the head, or a quick nod; but each of us carries his or her own solitude. We are invisible and we cannot be touched.

In my particular case, my butterfly is a powerful charm. Many times it has granted me passage through neighborhoods no white man has any business visiting after dark. Talismans, walk-aways, voodoo men and hellmarks and the Five Signs: almost every charm that isn't Chinese has come out of the slums, and for good reason. They are sinks of rage and fear, and the magic festers in them. The cops and the government have pulled out without telling anyone, bit by bit, year by year, abandoning them to their own bad dreams. The housing projects of Johnson's Great Society are haunted now, and deadly. Nobody knows how many people the minotaurs take each year.

I have seen teenage boys who would have gunned Dante down without a thought back away from me with fear in their eyes and cross themselves like Catholics. A block off Peter Street on one of my frequent routes there is an old woman who leaves out three olives as an offering for me every night.

I've taken to eating them when I go by.

* * *

It was in The Scrubs that I took this picture of two boys one night. Behind the body of a junked Camaro one is kneeling execution-style, his forehead on the road, his hands clasped behind his neck. The other boy is standing behind him with a gun, pressing the muzzle against the back of his victim's head.

It was three in the morning when I turned the corner and nearly walked into the execution. Everybody froze: me, the boy with the gun, the other members of the gang; everybody except for the victim, who was cursing quietly and continuously.

"Fuck." The boy with the gun stared at me in helpless fury. I stared at him the same way. He might have been fifteen.

He might have been fifteen years old and it was so unfair that I should have walked in on him at just that moment. So unfair that he should have to deal with a Visitation when he had other business.

I looked at him and I couldn't see a human thing.

Better people than I could have seen it in him somewhere, some spark of the Divine, but all I saw was a fifteen-year-old killer, a disgusting, unnatural monster. I would have crushed him like a scorpion if I could.

Instead I raised my camera to my shoulder, set the focus and squeezed the trigger, snapping shot after shot of him as he stood there with the gun in his hand. Shooting him again and again as his dumb rage grew, staring at me with utter hatred until his finger tightened and he blew out the other boy's, brains, again and again, emptying nine rounds into his head, all the time looking at me, looking at me, knowing he was caught, knowing he was a dead man, and there was nothing he could do.

I would take the film to the police and he would go to jail and there was nothing he could do about it. To him I was a magic thing, less human than the kid whose brains he had just spattered over the road. I was nothing but an instrument of his Fate.

The trial was quick and ugly and they made me testify. The prosecution moved to have the boy tried as an adult and the defense didn't bother to contest. The whole proceeding took forty minutes and the verdict was life.

I heard later he died in jail. They do a set of exams on each new' inmate and he scored too high on the Angel Test. Supposedly the scores are confidential, but a jail is of all places the most horrible: when a minotaur comes into being, it doesn't distinguish between the inmates and the authorities. So somehow the Angel Test scores always leak, somehow a weapon finds its way into another inmate's hands, and somehow the killer is never caught.

I call the picture “Minotaurs.”

Only we can't blame the magic for them. Magic is in all the headlines these days, like a fashionable disease, but it isn't the magic that fails to educate blacks and Latinos and poor white trash. It isn't the magic that keeps us from making a real commitment to creating decent jobs at decent rates of pay. It isn't the magic that makes four out of every five black boys grow up without fathers. The magic did not make the gangs; we made them ourselves.

These are not changelings: these are our children. In black and white, I shot one dead.

* * *

Jet looked through the viewfinder of his camera like a sniper looking through a scope, fixing it on the pagoda in the middle of the carp pool behind the Twelve Dreams Episcopal Church. On a park bench beside him Dante sat with his head resting wearily in his hands. He stared at the clay-colored water littered with lily and lotus pads long past blossoming. From time to time one of them would tremble as a big carp passed by, cruising for bread crumbs.

Snap.

Jet's camera whirred, advancing the film. "This is a truly rotten idea," he commented.

"The service will be over soon," Dante said stubbornly. "Then she'll come here to feed the carp. That's what she does on Sunday mornings."

"You've been here with her?"

"Well, no, but I'm sure that's what she said."

"What if it's too cold?" Jet sighed. "Look, D., I'm not trying to be a pain in the ass here. But by your own calculation you don't have a lot of time—"

"I'm aware of that, thanks."

"We should be doing something useful. Calling up the Angels' Guild, for instance."

"Then do it! There's a pay phone on the corner. Ask questions about Jewel. Be a detective. But I have to talk to Laura, okay?"

Jet grunted. "If you want my friendly advice, I don't think she's going to find this confession particularly endearing."

"Who the fuck asked you?" Dante snarled.

Jet shrugged and Dantc looked away. Overhead the bright sun seemed utterly warmthless. Omens roiled in the cloudy gray water, making lily pads tremble.

Twelve Dreams Episcopal stood on the border between the seedy downtown core and the gentrifying Chinatown.

Red brick buildings from the forties and fifties held herbalists and ink-and-stamp shops, a credit union, a handful of bakeries, and a pair of butcher shops with pressed ducks dangling in their windows. Local radio stations advertised on tall billboards; just beyond the church fence, with its line of autumn-withered bamboo canes, the

New China Times

building rested from the labor of putting out its Saturday shopping supplement.

Jet studied the cityscape. "Laura's an architect, isn't she? Successful one."

"Mm."

"Ever wonder why she lives in a cheap little apartment in your building?"

"How the hell should I know?"

Jet continued to study the city skyline rising around them. "My point."

Dante scowled.

The

China Times

gong had just sounded noon when a stream of parishioners trickled from the church into the gardens. While old women in polyester pants stood chatting on the church steps, a pack of children raced along the winding paths to the little pagoda that jutted over the water. Here they sat teetering on its bamboo rails and slapping one another on the back.

Laura always complained that with one parent from Shanghai and one from Kansas City, she should have been a great Eurasian beauty. Instead she was tall and cheerful and not overly coprdinated; on her best days she could just manage "professional" at work, and "coltish" in evening wear.

When she saw Dante waiting for her in the church gardens, she stopped and goggled like a startled marionette, grinning and clutching her straight black bangs in a parody of astonishment. She wore a black leather bomber jacket over blue jeans and a black turtleneck, and her silver Chrysler Tower earrings: one-inch-long replicas of the famous art deco skyscraper. In her hand she held a brown paper bag; bread crumbs for the carp, no doubt. She had Chinese eyes and a Kansas jaw and features more expressive than beautiful. She made one of her granny faces, peering suspiciously at Dante over the tops of her little round glasses. "You're so . . . white!" She pursed wide lips in a worried little frown and peeped at the other families strolling through the gardens. Quite a few of them were mixed, of course, but somehow Dante felt terrifically tall and pale and Hungarian. "What can this fish-faced omen mean?" Laura peered anxiously into her paper bag as if consulting an oracle, and then tossed Dante a bread crumb with a nervous granny toss.

"Studying the natives," he said. Usually it was the easiest thing in the world for Dante to joke with her, but today it took all his savoir-faire to stand in the garden of Twelve Dreams Episcopal Church like a solemn balding red-haired fish.

Laura laughed. "So what brings you here, heathen? Scanning the crowds of churchgoers for likely Break and Enter suspects?" Her quick eyes darted to Jet, still sitting on the bench beside the water. "Hi, Jet! It's been a long time."

"Just felt like seeing you," Dante said awkwardly.

"Too much family to bear for a whole long weekend, eh?"

Dante laughed nervously. "Yeah, I guess. Can't get rid of them," he added, nodding over at the bench.

Laura grinned, and then looked curiously between the brothers. "Say, Jet, are you an atheist too?"

Jet laughed. "Afraid so."

"How quaint! Dante's the only one I know my own age. Usually they're all old, you know. Hard to keep your unbeliefs, since the War."

"My father's doing," Dante explained. "It's some kind of ethical thing."

"Sarah is straying," Jet commented. "I catch her touching her cameo for luck sometimes. She's shopping around for a good God at a reasonable price."

Dante started, wanting to say,

Are you sure?

But of course Jet would know. He always knew this sort of thing.

While Dante never did.

Jet grinned. "But Dante and myself soldier on, the last acolytes of a dying non-faith."

Laura grinned back. "So have you come to smash the temple, or do you just want a chance to preach before the un-unbelievers?"

"Neither," Jet said. "Actually, Dante needs your help."