Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (20 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

The previous year, a development team at Data General was immortalized by Tracy Kidder's best selling book, "The Soul of a New Machine", about the ups and downs of developing a new mini-computer. Now it seemed like Mike Moritz was going to do something similar for the Mac team.

Mike Moritz in 1984

Over the next few months, Mike spent lots of time hanging around the Mac team, attending various meetings and conducting interviews over lunch or dinner, to learn our individual stories. Mike had grown up in South Wales and attended Oxford before moving to the US for grad school, obtaining an MBA from Wharton. He was in his mid-twenties, about the same age as most of us, and was very smart, with a sharp, cynical sense of humor, so he fit right in, and seemed to understand what we were trying to accomplish.

In December 1982, word somehow got around that Time Magazine was considering awarding Steve Jobs its prestigious "Man of the Year" designation for 1982. Mike Moritz, who was by now Time's San Francisco Bureau Chief, came down to Apple for another round of interviews, as background for the lengthy "Man of the Year" story. But we were in for a surprise when the award was announced the last week of the year.

Instead of crowning Steve Jobs as the Man of the Year as we expected, Time's editorial staff gave the designation to "The Computer", declaring 1982 to be the "year of the computer" and explaining that "it would have been possible to single out as Man of the Year one of the engineers or entrepreneurs who masterminded this technological revolution, but no one person has clearly dominated those turbulent events. More important, such a selection would obscure the main point. TIME's Man of the Year for 1982, the greatest influence for good or evil, is not a man at all. It is a machine: the computer."

The cover story did include another profile of Steve Jobs, containing some comments that were less than complimentary. One unspecified friend was quoted saying "something is happening to Steve that's sad and not pretty", but the best quote was attributed to Jef Raskin: "He would have made an excellent King of France."

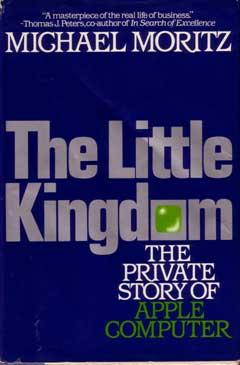

Mike's book

Steve became quite upset when he read an advance copy of the Time article on New Year's eve, and even called up Dan Kottke and Jef Raskin early on New Year's Day to complain to them about it. Soon, Mike Moritz was no longer welcome on the Apple campus; in fact, Steve told the software team "if any one of you ever talk to him again, you'll be fired on the spot!"

But some of us talked with Mike again surreptitiously, as he was putting the finishing touches on his book around the time of the Mac introduction. The book, entitled "The Little Kingdom: The Private Story of Apple Computer", was published in fall of 1984; twenty years later it remains one of the best books about Apple Computer ever written.

Perhaps inspired by the example of Steve Jobs and Apple, Mike Moritz switched careers in 1986 to become a venture capitalist, working for Don Valentine at Sequoia, one of the original investors in Apple. Mike became the original investor in Yahoo in April 1995, convincing Jerry Yang and David Filo to commercialize their web directory, and today is one of the most respected VCs in the industry.

Little Rubber Feet

by Paul Tavenier in January 1983

I was recruited to do the mechanical purchasing on the Mac in Dec of 1982. I was also one of a very few of the "Bozos" that were allowed to transfer over to the project from the manufacturing side of the Apple II business, as Steve Jobs had an extremely low regard for most everyone who worked there, and almost always hired from outside.

At a shortage meeting it was mentioned that the "little rubber feet" that mounted on the bottom of the case were not sticking where they belonged, and there was also trouble with availability from the supplier, Trend Plastics. In investigating this, I found that there was tooling that molded a custom rubber foot with a recessed Apple logo in it. Trend was a great supplier, but this part was a little unusual for them and they were having trouble sourcing the proper peel-and-stick adhesive for the job. We had paid about 8k for the tool, and the parts were something like two bits each.

At the next day's meeting, I mentioned that perhaps the design was a little overboard and maybe we should reconsider, as 3M had a standard part, called a "bump-on", that was available in the correct size, stuck to the case properly, and could even be molded in Apple beige if we desired. Cost was less than 2 cents.

OK, maybe what I really said was "This part is a real designer's wet dream, we need to lose it."

Jerry Manock, who was in charge of the industrial design group, was not even remotely amused. He wasn't even at the meeting, but someone ratted me out. (I would have made the comment even if he was there, that's just the way things were - you really could speak your mind.) He had also been contacted by the 3M rep, as that was the first guy I had called when chasing down shortages.

A very angry Jerry dragged me into a conference room. "Who authorized you to contact 3M about this part", he demanded. "I don't appreciate the wet dream comment either".

I replied that my job was to fill the shortages for the pilot build, and that I didn't need authorization from him or anyone else to contact a supplier. If he had a problem he could take it up with Matt Carter, who was then in charge of manufacturing.

We then called a truce, and went on to pretty much tolerate each other after that.

Trend made one more attempt to get the adhesive right and failed. Cost considerations won out, and every Mac shipped from Fremont left the plant with four 3M bump-ons stuck firmly to the bottom.

The Grand Unified Model (2) - The Finder

by Bruce Horn in January 1983

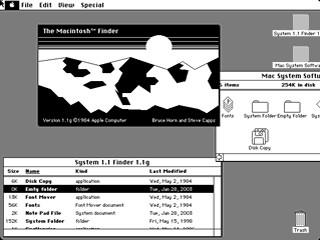

The Finder

One of the first things I did when I joined the Mac group was to begin working on the Finder. The first Finder, written in early 1982 with Andy's help, was a simple diskette image with tabs that represented the files on the disk. (see

early demos

). This Finder was the first to begin to take advantage of the idea of spatial organization: you could drag the tabs around and place them wherever you wanted on the floppy image. Also, my experience with Smalltalk showed through: the big "Do It" button was named after the Do It menu item in Smalltalk, which evaluated a selected expression. This Finder was actually usable, and served as a placeholder until the real Finder was available.

Immediately after the first Finder prototype, I wrote a second which was much more recognizable as the ancestor to the Finder that shipped. This prototype was a nonfunctional prototype that did not actually read the disk, but instead, read a text file that described a hierarchy of files within folders that would be displayed in windows. Our filesystem at the time did not have the concept of directories, so I had to fake it with the proof-of-concept prototype. This was the first Finder that provided double-clicking to open folders, documents, and applications; drag-and-drop to move files between folders; icon and list views; and persistent spatial locations of icons within windows. Of course, it was all window-dressing and none of it was functional, but it did give a good idea of what we would eventually want to implement. Unfortunately, it also made it look like the actual Finder implementation would be easy, which it most definitely was not.

Bill Atkinson came by and I gave him a demo. He had been thinking about the Lisa Filer, which was being written by Dan Smith and Frank Ludolph, and was dissatisfied with its design. When he saw in our Finder mockup some of the ideas that he had also seen in a MIT project called Dataland, he was convinced, and the IF (Icon Filer) project was born (see

rosing's rascals

). Bill, Dan and Frank put together a new Filer based on these concepts in time to ship with the first Lisa in 1983. In the meantime, I was working on the Resource Manager until later that year.

But I still couldn't get started on the Finder until I figured out how to handle files and applications. We were trying to make the Macintosh a very friendly computer, an information appliance, something that everyone could use. For example, one of the things that I felt could stand improvement in the current computing experience was the problem of filenames. In the Finder, I wanted to make it as easy as possible to give meaningful names to files without excessive restrictions placed on them.

At the time (and still, in some cases, now) filenames were very restricted, both in length and in format. Filenames had to have a three character suffix, with a dot, to denote their file types: text files were named "myfile.txt" and executable applications were named "word.exe". Filenames were also typically limited to eight characters, not including the suffix; this led to very cryptic naming on other computers, which we definitely wanted to avoid.

We decided that we needed to allow users to name their files whatever they wanted, with any characters, including spaces. Because the Finder would allow the user to simply click on a particular file to choose it, special characters like spaces would be no problem; in command-line systems, parsing filenames with special characters could be problematic.

The Grand Unified Model provided a framework for solving this problem too. Since resource objects were typed, indicating their internal data format, and had ID's or names, it seemed that files should be able to be typed in the same way. There should be no difference between the formats of an independent TEXT file, stored as a standalone file, and a TEXT resource, stored with other objects in a resource file. So I decided we should give files the same four-byte type as resources, known as the type code. Of course, the user should not have to know anything about the file's type; that was the computer's job. So Larry Kenyon made space in the directory entry for each file for the type code, and the Mac would maintain the name as a completely independent piece of information.

Simply storing the file type in the directory was not enough, however. There might be many different applications that could open files of a given type (say, a text file); how would the Mac know that a text file called "My Resume" needed to be opened in MacWrite, and another text file called "Marketing Plan" needed to be opened in WriteNow? Just knowing the file's type wasn't enough; the Finder also had to know which program created the file, and thus would be the best choice to open it. Thus another four-byte "creator code" would also be maintained, which would tell the Finder which program needed to be launched to open a particular document. For convenience, the user could also easily override this default, by dragging the document to whichever application he would like.

Finally, we also wanted to have useful and meaningful icons for programs and documents on the Mac. Using the type and creator mechanism, this was easy; we would just associate a specific icon for each file type that is handled by a particular application. Given a (type, creator) pair, it would be easy to look up the appropriate icon to draw for the file.

But where would these icons come from, and where would they be stored? It seemed clear that each program would be responsible for defining icons for the application and its documents, and that this information should be stored in the application itself; but if we simply opened the application's file each time we needed to draw an icon, the Finder would be terribly slow. I decided that the Finder needed to cache these icons and associations in a resource file. This was the Desktop Database.