Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (38 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

Tom and Vic had already encountered and surmounted a number of tough problems just to get scanning going at all. For example, the ImageWriter printer was not really designed to be stepped one scanline at a time, and if you tried that the paper would bunch up against the platen, causing distortion. Tom and Vic solved the problem by commanding the printer to move three steps up and then two steps back, instead of a single step up, which held the paper snugly against the platen as required. There were also various techniques for sensing the beginning and end of the scan line, and some timings that were determined by tedious experimentation for how long it took the printer to respond to a command.

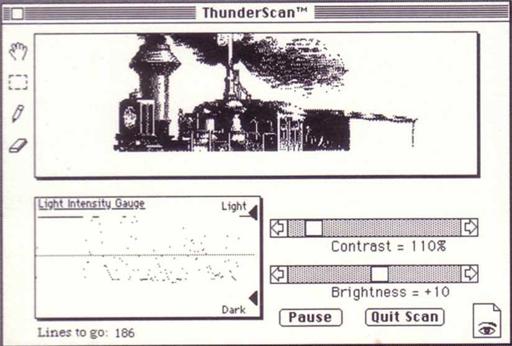

The Thunderscan application

(click to enlarge)

It took a week or so to get basic scanning working on the Macintosh, and then a few more days to render the gray scale data with Bill's modified Floyd-Steinberg dithering. After shaking out a variety of problems, mostly involving synchronization between the printer and the software, I was surprised and impressed by the consistent high quality of the results. I went through a brief, elated phase of scanning every image in sight that would fit through the printer, just to see how it would turn out.

One important design decision that I made early on was to keep the gray scale data around, to allow more flexible image processing. Thunderscan documents were five bits per pixel, before the Macintosh generally supported gray scale, and the user could manipulate the contrast and brightness of selected areas of the image, dodging and burning to reveal detail in the captured image. This also paid off in later versions when we implemented gray scale printing for Postscript printers.

My favorite feature that I came up with for Thunderscan had to do with two dimensional scrolling. Thunderscan documents could be quite large, so you could only show a portion of them in the image area of the window. You could scroll the image by dragging with a MacPaint-style "hand" scrolling tool, but you had to drag an awful lot to get to the extremes of a large image. I decided to add what I called "inertial" scrolling, where you gave the image a push and it kept scrolling at a variable speed in the direction of the push, after the mouse button was released. I had to add some hysteresis to keep the image from moving accidentally, and make various other tweaks, but soon I had it working and it felt great to be able to zip around large images by pushing them.

The hardest feature to perfect was bidirectional scanning. At first, Thunderscan only scanned from left to right, but it wasted time to return the scannner to the left after every scan line. We could almost double the speed if we scanned in both directions, but it was hard to get the adjacent scan lines that were scanned in opposite directions to line up properly. Ultimately, we made bidirectional scanning an optional feature, if you wanted to trade a little quality for greater speed.

I finished the software in November 1984, after taking a short break to work on something else (see

switcher

). Thunderscan shipped in December 1984, and did well from the very beginning, with sales gradually rising from around 1,000 units/month to over 7,500 units/month at its peak in 1987. For a while, it was both the least expensive and highest quality scanning alternative for the Macintosh, although I'm sure it frustrated a lot of users by being too slow. I did three major revisions of the software over the next few years, improving the scan quality and adding features like gray scale printing and eventually gray scale display for the Macintosh II.

Eventually, the flat bed scanners caught up to Thunderscan, and then surpassed it, in both cost, quality and convenience. Over its lifetime, Thunderscan sold approximately 100,000 units and improved countless documents by providing users with an inexpensive way to capture high resolution graphics with their Macintoshes.

Things Are Better Than Ever

by Andy Hertzfeld in September 1984

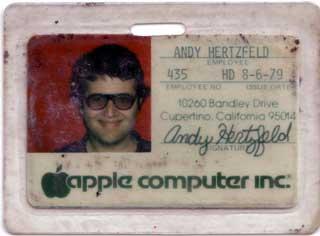

My Apple Badge

Toward the end of August 1984, my six month leave of absence (see

leave of absence

) was drawing to a close, and I still hadn't decided whether I would return to Apple. I continued to feel very close to the company, so it wouldn't be easy for me to turn in my badge, but I didn't see a reasonable alternative.

Either way, I was sure that I would continue to write software for the Macintosh, which was still brand new and overflowing with exciting opportunities for innovative applications (see

thunderscan

). I was confident that I could earn more money working independently than Apple was willing to pay me, even if you counted the appreciation of stock options, but financial matters were not my paramount consideration.

The main issue was that I wanted to be able to continue to make a difference in the Mac's evolution and I felt that no matter what I did on my own, it could only have a small fraction of the impact of work done for Apple. Even though things had gone relatively well so far, the Mac's long term success was far from certain, and it was entirely dependent on the moves that Apple made to evolve the platform.

Many of my closest friends were still working on the Mac team, so I heard a lot about what was going on at Apple. I usually drove down to Cupertino to visit them once every week or two, hanging out in the Bandley 3 fishbowl (see

spoiled?

), tentatively at first, but growing more comfortable when I saw that I was still welcome there. I lived next door to Mac hardware designer Burrell Smith, in separate houses on the same lot near downtown Palo Alto, so I heard about Burrell's trials and tribulations at work on a daily basis. Unfortunately, the news wasn't very encouraging.

The Mac team had merged with the Lisa team in Feburary 1984, a few weeks before I started my leave, creating a single large division. At the time, Steve Jobs claimed that the merger would help to transform the rest of Apple to be more like the Mac team, but to me it seemed like the opposite had occurred. The idealistic version of the Macintosh team that I yearned for had apparently vanished, subsumed by a large organization of the type that we used to make fun of, riven with bureaucratic obstacles and petty turf wars.

The core software group was still recovering from the intense effort to ship (see

real artists ship

) and hadn't done very much all spring and summer, suffering from a classic case of massive post-partum depression. The LaserWriter printer was the current main focus of development, along with the AppleTalk network required to support it, and the core software team didn't have much to do with either. No one had set a compelling new goal for the team, and now it was just drifting.

Burrell Smith had completed the LaserWriter digital board and moved on to work on the "Turbo Macintosh", a new Macintosh digital board featuring a custom chip that supported 4-bit/pixel gray scale graphics and a fast DMA channel to interface an internal hard drive. But Burrell frequently complained of sparring with engineering manager Bob Belleville and others on his staff over trivial design decisions. He thought that Bob didn't really want to add a hard drive to the Mac, favoring the development of a Xerox style "file server" instead, and was therefore trying to surreptitiously kill the Turbo project. I didn't think that Burrell would put up with it much longer; as he phrased it, he was "asymptotically approaching liberation" from Apple.

The one saving grace was that Bud Tribble had finally completed his six year M.D./Ph.D. program at the University of Washington and decided to forgo practicing medicine in favor of returning to his old job at Apple as Macintosh software manager, working for Bob Belleville. In July 1984, he moved into a spare bedroom at Burrell's house in Palo Alto, next door to mine, so I got to see him frequently. I still had the highest respect for Bud, and I loved to show him whatever I was working on because he always managed to improve it with an insightful suggestion or two.

I had mixed feelings about returning to the lumbering Macintosh division, but Bud was a strong link to the good old days and I thought that perhaps we could establish a little outpost in the large organization where the original Macintosh values could prevail. But that didn't seem possible if Bud worked for Bob Belleville, my nemesis whom I blamed for many of the problems. The only solution I could think of was for Bud to work directly for Steve Jobs instead of working for Bob. Bud was all for it, but only Steve could make it happen. I called Steve's secretary Pat Sharp, and arranged to have dinner with Steve and Bud to discuss my possible return to Apple.

We met in the lobby of Bandley 3 and walked to an Italian restaurant on De Anza Boulevard a few blocks away. Steve seemed a bit preoccupied, and I was nervous about how he would react to what I had to say, because I had to implicitly criticize him to make my case. After we ordered dinner I cleared my throat and tentatively plunged ahead.

"As you know, I care a lot about Apple, and I really want to return from my leave of absence. I'd love to work for Bud again, but things seem really messed up right now." I paused for a moment as I gathered my resolve. "The software team is completely demoralized, and has hardly done a thing for months, and Burrell is so frustrated that he won't last to the end of the year..."

Steve cut me off abruptly with a withering stare. "You don't know what you're talking about!", he interrupted, seeming more amused than angry. "Things are better than ever. The Macintosh team is doing great, and I'm having the best time of my life right now. You're just completely out of touch."

I couldn't believe what I was hearing, or tell if Steve was serious or not. I looked to Bud, who communicated his bewilderment with an apologetic shrug of his shoulders, but I could see that he wasn't going to corroborate my views.

"If you really believe that, I don't think there's any way that I can come back," I replied, my hopes for returning sinking fast. "The Mac team that I want to come back to doesn't even exist anymore."

"The Mac team had to grow up, and so do you," Steve shot back. "I want you to come back, but if you don't want to, that's up to you. You don't matter as much as you think you do, anyway."

I saw that we were so far apart that there was little point in continuing the conversation. We finished dinner quickly and walked back to Apple without further discussion.

Actually, quitting was easier than I thought it would be; I just called up Apple's HR department and let them know that I wouldn't be coming back. I didn't even have to sign any paperwork or turn in my badge, which I still have today, almost twenty years later. I had thought it would feel devastating to finally resign, but instead I actually felt relieved for the situation to be resolved, and optimistic about writing Macintosh software on my own.

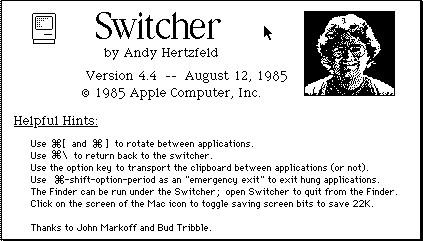

Switcher

by Andy Hertzfeld in October 1984

The Switcher About Box

The first commercial product that I worked on after going on leave of absence from Apple in March 1984 (see

leave of absence

) was a low cost, high resolution scanner for the Macintosh called Thunderscan, that I created in collaboration with a tiny company named Thunderware (see

thunderscan

). I started working on it in June 1984, and by early October, it was almost complete.