Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (35 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

In the Finder, the startup disk would appear on the desktop, in the top-right corner, ready to be opened. The Finder would initially select it; once selected, typing would replace the current name, following the modeless interaction model that I had learned in the Smalltalk group from Larry Tesler. This meant that whatever anyone typed when they first came up to the Macintosh would end up renaming the disk.

We had done some user testing, but apparently not enough; our users were already too experienced with the Mac to make this type of mistake. We apparently didn't ask enough people to find out if the Finder passed the "Mom test": would your Mom be able to figure it out without help?

I hurried back to the office and worked on a new release of the Finder that would fix the bug (and others that I had discovered)--it would require the user to take an extra step before she would be allowed to rename the disk.

Finally seeing how the public used the Mac made it clear to me that there were, in fact, good reasons for modes--at least in some cases--and it certainly gave me a taste of humble pie.

Disk Swapper's Elbow

by Steve Capps in January 1984

One of the more common afflictions of early Macintosh users was the dreaded "Disk Swapper's Elbow" caused by a disk copying operation run amok. Disk swapping was a necessary evil caused by having 400KB floppy disks, 128KB of RAM, and a single floppy drive. If a user wanted to make a backup of a disk, she had to eject the source disk, insert a blank one, format it, drag the source disk over the new disk, and then the Finder would copy data piece-by-piece with the necessary swapping.

A typical application on a 128K Mac had about 85K of memory available; the rest was used by the system, mostly for the bitmap display. A simple calculation shows that copying a 400K disk should involve about 5 or 6 swaps. Five disk swaps was barely tolerable, but, as early Finder users will remember, occasionally it would take well over 20 disk swaps.

You'd start a disk copy and hold your breath during the fifth, and hopefully, final swap. If the Mac dutifully disgorged the floppy that sixth time, you'd convince yourself you miscounted, cross your fingers, and hope for the best. By the seventh swap you start cursing because you knew you were trapped and you'd start wondering about investing in a second, external drive.

Even though the whole Finder was only 46K of code and had about 10K of overhead, the remaining 30K of memory was too small for practical copying. So, I had to break up the code into two chunks: the bare minimum for copying and all the rest. Then, I had to carefully flush out all data that was cached in memory, preload the small disk-copying chunk of code, and coalesce the balance of RAM. Usually, the Finder ended up with 75K of free memory and things worked as planned. But, sometimes the system would mysteriously reload the larger chunk of the Finder code, fragment the free memory, and cause another case of Disk Swapper's Elbow.

It took me a long time to figure out what happened because we had rarely seen this in testing. There were a few bug reports of this problem that were never reproducible. The bug reports went like this: "Copied a disk, it took 20+ swaps $%#@!!! Tried a second time, it was fine." The reason this was not reproducible was because we were all expert mouse users and usually skipped the crucial misstep.

When anybody first starts using a mouse, dragging is one of the more difficult things to do. It's actually quite awkward to click down, move the mouse while holding down the button, and then release. Beginners very often accidentally release the mouse button while dragging. In the Finder, this means you could "drop" an icon you were dragging. You rarely thought about this (unless you happened to drop it over a folder and it disappeared); you'd immediately pick the icon up and continue the drag. It turned out if you dropped the disk icon during a disk copy, you'd induce the bug. Since all of the team members had been using the mouse for years by this time, we rarely dropped icons which is why we could never reproduce the problem.

To support the user's spatial memory, the Finder always remembered where icons were located on the desktop. When you dropped the icon -- even for a half a second -- the Finder would dutifully record its location. The routine to save the icon's location was, as you probably guessed, in the big portion of the Finder's code. When this bug occurred, the Finder would carefully massage the memory for copying and then belatedly discover the icon's location hadn't been flushed out. It would blindly call the routine to flush it and you now know what would happen...

I introduced this bug about 2AM the morning we built the final disks. This bug was caused by a fix to a much more egregious bug, so it was definitely the lesser of two evils....really!

Real Artists Ship

by Andy Hertzfeld in January 1984

Chocolate Covered Espresso Beans

By the fall of 1983, we had committed to announcing and shipping the Macintosh at Apple's next annual shareholder's meeting, to be held on January 24th, 1984. The failure of the Twiggy disk drive almost caused us to be late (see

quick, hide in this closet!

), but it seemed like the new Sony 3.5 inch drive solved all of our problems, and the rest of the hardware was ready to go. The Macintosh ROM was frozen in early September and sent out for fabrication. All that remained was finishing the System Disk, and our two applications, MacWrite and MacPaint.

The software team worked hard over the Christmas break of 1983. The Finder still wasn't finished, and there were lots of performance problems, especially when copying files between disks, which seemed interminable. There was lots of integration testing to do, like cutting and pasting between applications, or applications interacting with desk accessories. As the New Year rolled around, it was clear that we were running out of time.

By the first week of January, the software team was working around the clock, testing and fixing problems that were found. Every employee in the building was drafted as a tester, and we held a series of dinners where Apple bought catered food for anyone who stayed late to test (see

90 hours a week and loving it

).

Finally, the deadline for finishing the software was less than a week away, and it seemed obvious that there were still too many bugs for us to ship it. Late on Friday evening, we convinced ourselves that we needed an extra week or two to fix the remaining problems. Steve Jobs was on the East Coast, along with Bob Belleville and Mike Murray, doing press for the introduction, so we arranged for a conference call early Sunday morning to tell him about the slip.

Jerome Coonen, our software manager, spoke for the team, as we gathered around the speakerphone. We were exhausted, and progress was slow. There were still bugs that we hadn't gotten to the bottom of yet, and it didn't seem possible that we could make it in the time remaining. Jerome proposed that we ship "demo" software to the dealers for the introduction, and update all the customers with final software a few weeks later. We thought Jerome was pretty persuasive as we held our breath waiting for Steve to respond.

"No way, there's no way we're slipping!", Steve responded. The room let out a collective gasp. "You guys have been working on this stuff for months now, another couple weeks isn't going to make that much of a difference. You may as well get it over with. Just make it as good as you can. You better get back to work!"

We did manage to wrangle an extra couple of days, by virtue of working the weekend and moving the deadline to 6am Monday morning, when the factory opened, instead of Friday afternoon. We agreed to go home and rest up, and then come into work on Monday ready for the final push.

The final week was one of the most intense I ever experienced. Steve wanted Bill Atkinson and myself to fly to New York to present a Mac to Mick Jagger, but I decided that I needed to stay in Cupertino to help with the bug fixing. Some of us were pausing work to get photographed for magazines like Newsweek and Rolling Stone, which made others on the team feel terrible that they were being left out. At times, the atmosphere got pretty tense.

Friday finally rolled around and it was clear that there were still too many bugs in both the Finder and MacWrite. Randy Wigginton brought in a gigantic bag of chocolate covered espresso beans, which, along with medicinal quantities of caffeinated beverages, helped us forgo sleep entirely for the last couple of days. We starting doing release cycles that were only a few hours apart, re-releasing every time we fixed a significant problem.

When a new release was ready, we would all grab it and start testing again. At one point, around 2am on Sunday night, I stumbled across a bug in the clipboard code. I thought I knew what it might be, but I was so tired that I didn't want to deal with it. I tried to pretend that I didn't see the problem, but Steve Capps was watching my expression and knew there was something wrong. I also was too tired to sustain a pretense; he grilled me about the problem and then helped me craft a fix, since I was too tired to do it on my own.

Around 4am, we had a release where everything seemed to go wrong - even MacPaint was crashing, which was usually rock solid. But our final release, around 5:30am seemed to be much better; the worst problems seemed to have receded and we thought we might actually have a decent release candidate.

We all focused on testing the final release as much as we could until 6am, when Jerome would have to leave to drive it to the factory. It looked pretty good, but soon someone found a potential show stopper - the system seemed to hang when a blank disc was inserted during MacWrite - the disk didn't start formatting like it should. I realized that it was probably hung up waiting for an event, so I reached out and tapped on the space bar, and formatting commenced. Jerome thought the bug was bad enough to hold up the release, but he left to drive it to the factory anyway, figuring they needed to start duplication even if it was just going to be a demo release.

The sun had already risen and the software team finally began to scatter and go home to collapse. We weren't sure if we were finished or not, and it felt really strange to have nothing to do after working for so hard for so long. Instead of going home, Donn Denman and I sat on a couch in the lobby in a daze and watched the accounting and marketing people trickling into work around 7:30am or so. We must have been quite a sight; everybody could tell that we had been there all night (actually, I hadn't been home or showered for three days).

Finally, around 8:30 Steve Jobs arrived, and as soon as he saw us he immediately asked if we had made it. I explained the formatting bug to him, and he thought that it wasn't a show stopper, which meant that we were actually finished. I finally drove home to Palo Alto around 9am and collapsed on my bed, thinking that I'd sleep for the next day or two.

The Times They Are A-Changin'

by Andy Hertzfeld in January 1984

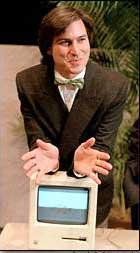

Bow-tie era

Steve Jobs

January 24, 1984 - the big day had finally arrived. We had looked forward to the date for so long that it didn't seem real to be actually experiencing the long-awaited public unveiling of the Macintosh at Apple's 1984 annual shareholder's meeting. We were excited, of course, but also nervous about our hastily contrived demo software, and still exhausted from the final push to finish the system software (see

real artists ship

)

I attended one of the rehearsals held over the weekend, to help set up the demo, and it was fraught with problems. Apple rented a powerful video projector called a LightValve, that projected the Macintosh display larger and brighter than I thought possible. But the Mac had to be connected to the projector through a special board that Burrell cooked up to compensate for the Mac's unique video timings, and the LightValve seemed to be quite tempermental, taking eons to warm up and then sometimes shutting down inexplicably. Plus, Steve wasn't into rehearsing very much, and could barely force himself into doing a single, complete run-through.