Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made (42 page)

Read Revolution in the Valley: The Insanely Great Story of How the Mac Was Made Online

Authors: Andy Hertzfeld

Tags: #Business & Economics, #General, #Industries, #Computers & Information Technology, #Workplace Culture, #Research & Development, #Computers, #Operating Systems, #Macintosh, #Hardware

We had a pleasant dinner, huddled around one end of the long table, mainly reminiscing about the good old days developing the Mac but occasionally engaging in grim speculation about Apple's future. Steve had arranged for some gourmet vegetarian food to be delivered, and we drank some excellent wine. Dessert consisted of handfuls of locally grown Olson's cherries, grabbed from a large wooden crate that Steve kept in the kitchen.

After dinner, we retired to another room that had an expensive stereo system and an elaborate model of the mostly underground house that Steve planned to build to replace the one we were standing in. I had brought along a copy of Bob Dylan's new album with me, "Empire Burlesque", which was just released earlier that week, because I knew that Steve, like myself, was a big Bob Dylan fan, although Steve thought that Dylan hadn't done anything worthwhile since "Blood on the Tracks" a decade ago. I placed the album on a hi-tech turntable that seemed to be mounted on aluminum cones and played the last song, "Dark Eyes", which was slow and mournful, with a sad, fragile melody and lyrics that seemed relevant to the situation at Apple. But Steve didn't like the song, and wasn't interested in hearing the rest of the album, reiterating his negative opinion of recent Dylan.

Later, when it was time to leave, we lingered outside under the beautiful summer night sky. We were all pretty emotional by then, especially Steve. I tried to convince him that the change wasn't necessarily so bad, and that I would be excited about returning to Apple to work with him on a small team again. But Steve was inconsolable, and more depressed than I had ever seen him before. As we left, I thought that it was lucky that he had Tina there to keep him company in the cavernous mansion.

It took a while for me to understand the consequences of the reorganization. The best news for me was that my nemesis Bob Belleville had resigned from Apple, because he had sided with Steve during the recent infighting and burned too many bridges to continue. Most of the rest of Steve's staff stayed on to work for Jean-Louis Gassee, who replaced Steve in the reorganized division, although Mike Murray resigned soon thereafter. Steve Jobs spent most of the summer traveling, trying to figure out what to do next. He was still the chairman of Apple Computer, but he was so at odds with the rest of its leadership that it was hard to see how he could remain there much longer.

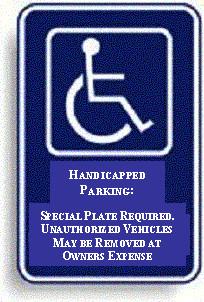

Handicapped

by Andy Hertzfeld in 1985

Most of the anecdotes that I've written for Folklore are based on incidents that I observed myself, but sometimes a second or third hand story is just too good to pass up. I have to issue a disclaimer here that I didn't actually witness the punch line to this one, and it certainly seems too good to be true.

Steve Jobs was not the most considerate individual at Apple, and he had lots of ways to demonstrate that. One of the most obvious was his habit of parking in the handicapped spot of the parking lot - he seemed to think that the blue wheelchair symbol meant that the spot was reserved for the chairman.

Whenever you saw a big Mercedes parked in a handicapped space, you could be sure that it was Steve's car (actually, it was hard to be sure otherwise, since he also had a habit of removing his license plates). This sometimes caused him trouble, since unknown parties would occasionally retaliate by scratching the car with their keys.

Anyway, the story is that one day Apple executive Jean-Louis Gassee, who had recently transferred to Cupertino from Paris, had just parked his car and was walking toward the entrance of the main office at Apple when Steve buzzed by him in his silver Mercedes and pulled into the handicapped space near the front of the building.

As Steve walked brusquely past him, Jean-Louis was heard to declare, to no one in particular - "Oh, I never realized that those spaces were for the emotionally handicapped...".

One day in October 1983 I got a phone call at my desk at Apple from the Cupertino police department saying something like, "You reported that Mercedes parked in the handicapped space at your lot at Apple. Well, we sent a car out there but we can't really tow it away because the handicapped space is improperly designated."

I had no idea what he was talking about. A few hours later, I found out that Apple's other cofounder, Steve Wozniak, who was a prolific prankster, called up the Cupertino police and reported that a silver Mercedes was illegally parked in a handicapped space and told them the person reporting it was Andy Hertzfeld, giving them my phone number at work. I decided not to inform Apple's facilities department about the improperly marked space, just in case Woz decided to try it again.

MacBasic

by Andy Hertzfeld in June 1985

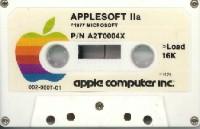

Applesoft Basic Cassette

When the Apple II was first introduced in April 1977, it couldn't do very much because there were few applications written for it. It was important to include some kind of programming language, so users, who were mostly hobbyists, could write their own programs. "Basic", which was designed for teaching introductory programming by two Dartmouth professors in the 1960s, became the language of choice for early microcomputers because it was interactive, simple and easy to use. The Apple II included a Basic interpreter known as "Integer Basic", written from scratch by Steve Wozniak, which was almost as idiosyncratically brilliant as his hardware design, stored in 5K bytes of ROM on the motherboard. It also came with Microsoft's Basic interpreter, dubbed "Applesoft Basic", on cassette tape. Sadly, Applesoft eventually displaced Integer Basic in ROM in the Apple II Plus because it had the floating point math routines that Woz never got around to finishing.

Donn Denman started working at Apple around the same time that I did, in the summer of 1979. His job was to work with Randy Wiggington on porting Applesoft Basic to the Apple III. They needed to rewrite parts of it to deal with the Apple III's tricky segmented memory addressing, as well as porting it to SOS, the new operating system designed for the Apple III. It was easy for me to track Donn's steady progress because he sat in the cubicle across from mine when we moved into Bandley III in the spring of 1980.

By the summer of 1981, the Macintosh project was beginning to hit its stride, and we started thinking about the applications that we wanted to have at launch to show off the unique character of the Macintosh. Besides a word processor and a drawing program, we thought that a Basic interpreter would be important, to allow users to write their own programs. We decided we should write it ourselves, instead of relying on a third party, because it was important for the Basic programs to be able to take advantage of the Macintosh UI, and we didn't trust a third party to "get it" enough to do it right.

I still had lunch with some of my friends in the Apple II group a couple of times a week, and I started trying to convince Donn to join the Mac team to implement our Basic. He was reluctant at first, since the Mac project was still small and risky, but he was pretty much finished with Apple III Basic and was full of ideas about how to do it better. He eventually couldn't resist and joined the Mac team in September 1981.

A Basic interpreter consists of a text editor for inputing your program, a parser to translate it into a series of byte codes, and an interpreter to execute the byte-coded instructions. Donn wrote the interpreter first, and then hand-coded some byte codes to test it. He implemented some graphics primitives early on, since they were nice to demo. In a few months, he had a pretty impressive demonstration program going that drew elaborate graphical trees recursively, in multiple windows simultaneously, showing off the interpreter's threading capabilities.

By the spring of 1982, it was apparent that Donn needed some help if we wanted Basic ready for the introduction, which at the time was supposed to be in January 1983. We decided to hire Bryan Stearns to help him, who Donn knew from the Apple II team. Bryan was only 18 years old, but he was excited about the project and Donn thought they worked well together, so we gave him a chance.

But Basic still had a hard time getting traction, especially since the system was evolving rapidly beneath it. After six months or so, I was surprised to hear that Bryan was quitting the project to work at a tiny start-up founded by Chuck Mauro, who I had helped with his 80 column card for the Apple II. I tried to talk him out of it but he left anyway. By the spring of 1983, it was so obvious that Basic wouldn't be ready for the introduction that the software manager, Jerome Coonen, pulled Donn off of it to work on other parts of the ROM and the system. Donn worked on desk accessories and wrote the alarm clock and notepad, as well as the math guts of the calculator (see

desk ornaments

).

After the Mac shipped in January 1984, Donn went back to work on Basic with renewed vigor, determined to get it finished. Apple brought in some free-lance writers to write books about it (including Scot Kamins, who was a co-founder of the first Apple users group in the Bay Area). But Microsoft surprised us, and released a Basic for the Macintosh that they didn't tell us they were developing. It was everything that we expected and feared, since it was essentially console-based - it didn't really use the Mac user interface. Donn was making good progress and looked to be on track to ship in early 1985; we were excited to show the world what Basic should really look like on the Macintosh.

Unfortunately, there was another problem on the horizon. Apple's original deal with Microsoft for licensing Applesoft Basic had a term of eight years, and it was due to expire in September 1985. Apple still depended on the Apple II for the lion's share of its revenues, and it would be difficult to replace Microsoft Basic without fragmenting the software base. Bill Gates had Apple in a tight squeeze, and, in an early display of his ruthless business acumen, he exploited it to the hilt. He knew that Donn's Basic was way ahead of Microsoft's, so, as a condition for agreeing to renew Applesoft, he demanded that Apple abandon MacBasic, buying it from Apple for the price of $1, and then burying it. He also used the renewal of Applesoft, which would be obsolete in just a year or two as the Mac displaced the Apple II, to get a perpetual license to the Macintosh user interface, in what probably was the single worst deal in Apple's history, executed by John Sculley in November 1985.

When Donn found out that MacBasic had been cancelled, he was heart-broken. His manager told him "it's been put on hold indefinitely" and instructed him to destroy the source code and all copies, but refused to answer Donn's questions about what was going on. Later that day Donn went for a wild ride on his motor cycle and crashed it, returning home scraped up but with no real damage, except to his already battered ego.

Bill Atkinson was outraged that Apple could treat Donn and his users so callously, and let John Sculley know how he felt, but the deal was done and couldn't be reversed.

Donn quickly filed for a leave of absence, but eventually returned to Apple to work on various projects, including AppleScript.

The Beta version of MacBASIC had been released to interested parties, including Dartmouth University which used it in an introductory programming class. Apple tried to get back all the copies, but the Beta version was widely pirated, and two books on MacBASIC were published, and sold quite well for several years.

An Early 'Switch' Campaign

by Tom Zito in September 1985