Richard The Chird (59 page)

Authors: Paul Murray Kendall

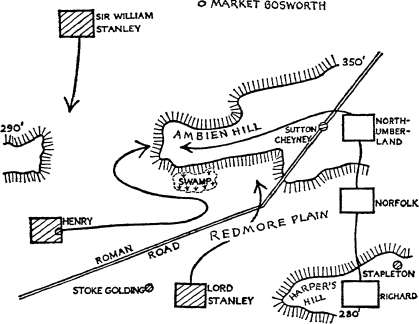

As he approached the western extremity of Ambien Hill, Richard could see all three camps of his enemies. Both Lord Stanley's men and his brother's were standing to arms, motionless; but whereas Lord Stanley's were on foot, as was customary, Sir William's were mounted. 6 * Henry Tudor and his commanders had been taken by surprise. Their army was hastily moving eastward from its camp in order to interpose the swamp on the southern slope of Ambien Hill between it and the royal host occupying the summit. Norfolk was arranging his ranks a little way down the slopes in the shape of a bent bow pointing almost due southwest at the rebel camp, with a clump of archers on the left facing

south toward the swamp, men-at-arms in the center and a clump of archers on the right facing west toward Shenton. 6 *

As Richard was disposing his division on the hilltop, the enemy trumpets rang out. It was they who would begin the battle —indeed, what was left for them? They came swinging around the western edge of the swamp led by John de Vere, Earl of Oxford, striding beneath his banner of a star with streams. Norfolk's archers assailed their ranks with a storm of missiles and were in turn galled by the arrow fire of the advancing enemy and their reserve. Guns cracked; stone cannon balls bounded on the upper slopes. 7 The rebels had picked up some artillery at Lichfield and perhaps at Shrewsbury. The King's men replied with guns and serpentines, but they were few in number. The great arsenal in the Tower, Richard had not drawn on. Cannon served to reduce castles, defend a city, or stiffen a defensive position. The invaders of his realm Richard had thought only of attacking. Still the mass of foot soldiers poured around the swamp until they had reached a point almost halfway across the western base of the hill. Their right rested on the swamp; then-left flank was in the air—unless Sir William Stanley supported it with his cavalry, massed orjy a quarter of a mile away to the north. While the hot exchange of arrow fire continued, the rebels momentarily halted, their ranks shifting to face up the hill, where the bent bow of Norfolk's line stood ready.

The respective numbers of the hosts can only be approximated. Henry Tudor had brought to the field about 5,000 men—2,000 French, 400 or 500 exiles, 500 men of the Shrewsbury interest, 2,000 Welsh and English adherents—the former in the majority —who had joined him on his march. Of these, Oxford, trusting in the Stanleys, had committed about 4,000 men to his attack. The remainder were divided into two bodies, one remaining on the plain behind the right wing, the other taking its station on the rising ground opposite the west end of Ambien Hill (not many yards from the present railway station). Sir William Stanley mustered some 2,500 men; Lord Stanley counted perhaps 5,500 or 4,000.

Richard's host outnumbered Henry Tudor's almost two to

one; it was smaller, however, than the combined forces of the rebels and the Stanleys. The King had led to Ambien Hill an army of perhaps 9,000 men—about the same size as that with which Edward had met Warwick at Barnet. Of these, 3,000 stood idly at the rear of the ridge under Northumberland's standard, leaving some 6,000 available troops. Norfolk's vanguard numbered approximately 2,500 men. From his center, 3,500 strong, Richard had reinforced the Duke with about 1,500 soldiers to bring the vanguard up to the numbers of the enemy mass at the foot of the hill. Of his remaining 2,000 men, Richard had probably posted a few hundred on the southern brow of the hill, east of the swamp, to guard against a sudden attack by Lord Stanley, who had now advanced from his camp to a position on Redmore Plain only half a mile from the hill. The King had sent another small detachment to the northwest brow of Ambien, in order to protect Norfolk's flank against assault by Sir William Stanley. Both forces were spread thin to mask their weakness. There remained probably 1,000 men for the general reserve, of whom some fourscore warriors in shining mail, the Knights and Esquires of the Body, were stationed close about the King and his standard.

As Richard scanned the battlefield, his glance turned often to the two bodies of the enemy reserve. Soon he called for men of specially keen sight who had some skill in heraldic bearings. Those who volunteered he dispatched forward with one brief injunction: Find out where Henry Tudor has stationed himself.

The trumpets of the enemy rang out. A bedlam of commands in Welsh, French, English rose on the air. The mass of rebel troops began to climb the hill. Norfolk's trumpets sounded. Norfolk and Surrey, Lord Ferrers, Lord Zouche, and their captains shouted orders. With a yell the royal army plunged down the hill. The arrow fire and the banging of guns ceased. Midway down the slope the two hosts collided with a crash of steel and were instantly locked in combat. Norfolk's ranks were thinner than the enemy's. He had lengthened his line to cut around the flanks. In the center his banner of the silver lion waved against Oxford's star with streams. Richard stood motionless on the hilltop, watch-

ing. The lines bulged, swayed like the throb of the sea, foaming with a surf of axes, swords, spears. Slowly, raggedly, the royal ranks gave a little ground. The pressure was greatest in the center, where Oxford headed a massive phalanx. Norfolk's line bent backward, began to take the shape of a crescent. In one spot it was wearing dangerously thin; Richard gave a command; a knight moved forward with a detachment of the reserve to bolster the crescent. The center held; and now Norfolk's tactics began to succeed. The horns of the crescent were goring the enemy flanks, driving them inward. The left flank, which had no anchorage, was crumbling. Oxford's trumpets shrilled: Retire to the standards! Welsh—French—English voices roared the commands above the din of battle. Oxford's men pulled back, massed themselves about the banners of their leaders. Momentarily bewildered by the maneuver, the royal army permitted them'to disengage. A lull fell upon the field. A few feet apart, the forces glared at one another, panting for breath. Oxford's flanks, reinforced from the reserve, were now drawn inward; his army took on the shape of a wedge or rough triangle, the point aimed at the hilltop.

Norfolk stood looking along his line. His gruff and able son Surrey was waiting at his side. Zouche and Ferrers waved steel-gauntleted arms. As the Duke's trumpeters sounded the call to battle, his men hurled themselves once more upon the enemy. In the thickest of the press, Norfolk was showing himself worthy of the lion on his shield. A West Country father and son, yeomen named Brecher, did such execution that Oxford's lieutenants marked them in memory, Zouche and Ferrers were pressing hard on the flanks.

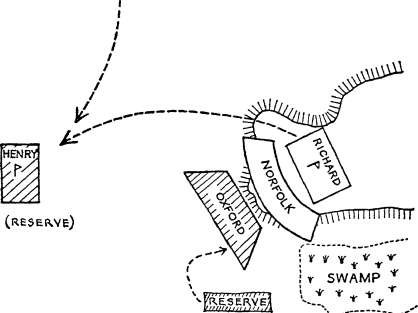

One of the men of keen sight came running to King Rich-He and his fellows had marked out him who must be Henry Tudor—there to the west on the rising ground opposite—the figure on horseback, close by the red-dragon standard—he there in the center of a mounted reserve of some twenty-five score men. Richard strode forward the better to see, straining his eyes against the dust of combat At last he made out the figure, saw a messenger run up and do obeisance; it must be the Tudor.

A strange peace descended upon him, even as he instantly determined to exploit this opportunity which he had so long hoped for. He made no calculations of success; his mind had room only for decision. Yet, he was aware that to come down upon Henry Tudor in a surprise attack could clinch a quick and dazzling victory. If their Pretender were slain, the rebels would have nothing

O A\ARKET

THE EVE OF BOSWORTH

to fight for; when the fatal word ran across the field, they would take to their heels or surrender, and the Stanleys would hasten to include themselves among the victors. The risks were of course enormous. He and the men of his Household would have to ride directly across Sir William Stanley's front against a body of troops probably five times larger. And he himself must cleave his way to Henry Tudor before the rebels could rally or Sir William intervene. It was a desperate stroke, for failure meant absolute disaster, but it did hold a chance of brilliant victory. The core

BOSWORTH FIELD

439

of his purpose, however, was simply to hurl himself against the man who had poisoned his peace and racked his kingdom* When he struck at Henry Tudor he would put a quick end, one way or the other, to his own agony of spirit and to the slaughter of his subjects. He would attack with the men of his Household only, for they were the sworn defenders of his body whose loyalty

» SIR WM. STANLEY

THE BATTLE OF BOSWORTH

he had nurtured with his good lordship. None else would he ask to share this journey into peril.

Back he strode to the standard to give his orders. Attendants ran to the rear, where a band of war steeds had been tethered. The men of the Household began to look to their weapons.

One of the King's squires cried out that John Howard was down. There, by the banner of the silver lion, was a swirl of fighting men. Surrey was laying about him furiously. A messenger raced up the slope to the King's standard—the Duke of Norfolk

had been slain. As Richard ordered a detachment of the reserve to Surrey's aid, another messenger arrived with the news that Lord Ferrers had been cut off from his men and killed. Richard's eye was caught by a horseman galloping across Redmore Plain. He would be bearing Henry Tudor's tidings to Lord Stanley that Norfolk was no more. Richard now sent a message to the Earl of Northumberland, commanding him to advance at once to the support of the royal army. Northumberland must be made to reveal to the world the color of his allegiance.

The horses were led forward. The men of the Household quieted their mounts, tightened armor plate and saddles. Northumberland's reply arrived: the Earl felt it his duty to remain in the rear in order to guard against Lord Stanley. It was what Richard had expected. William Catesby came forward nervously, his face drawn with fear—the King must seek safety in flight while the way w r as still open . . . the Stanleys would advance at any moment against them . . . the loss of a single battle need not be serious. . . .

The King shook his head impatiently, turning away; Catesby retired, but not to ride with his sovereign lord.

With the aid of his squires Richard mounted his white courser. Behind him, the Household swung into the saddle. He turned to look at them, the Knights and Esquires of his Body—Sir Richard Ratcliffe, Sir James Harrington, Sir Marmaduke Constable, Sir Thomas Burgh, Sir Ralph Assheton, Sir Thomas Pilkington, John Sapcote, Humphrey and Thomas Stafford. . . . They were all men who had done him good service in peace and war. Close behind him was his faithful Constable of the Tower, Sir Robert Brackenbury, and there, of no noble stock but in full armor today and ready to do knightly service, was his secretary, John Kendall. Beside him waited his friends Francis, Viscount Lovell, and Sir Robert Percy.

The battle was scarcely half an hour old; the bulk of the royal reserve was uncommitted; the Stanleys still waited. ... No matter.

Richard rose in his stirrups so that all might hear. "We ride to seek Henry Tudor." Their faces showed that they understood,

BOS WORTH FIELD

and awaited only his command. He closed his visor. One of his squires put the battle-axe in his grip. He raised his gauntleted arm to signal his trumpeters. For the last time there sounded in the ears of men the battle call of the fierce and valiant Plantagenets.

His horse moved forward at a walk, the men of the Household pacing close beside and behind him. Northwestward down the slope he rode to swing clear of the northern end of the battle line. Now the cavalcade gathered speed. At the head of less than a hundred men, the King of England, his golden crown flashing on his helmet, was charging the mass of the enemy reserve. Once he had reached the bottom of the hill, Richard urged his horse to a gallop, hooves thundering behind him. His mind was riveted upon the encounter to come, but he must have experienced a thrill of pride in the fellowship which rode like one man at his shoulder. They did not weigh the hazard he ordered them to dare. They did not ask him if his quarrel were good. Loyaulte me lie. . . . Perhaps now his mighty brother came to him, smiling, as he had smiled once upon a time, standing beneath the great sun banner in the moment of victory at Barnet.