Rome: An Empire's Story (28 page)

Cicero’s correspondence mentions many other Greek writers who lived for decades in Italy as guests of the Roman aristocracy. They came not only from great eastern centres like Athens and Rhodes and Alexandria, but also from Greek cities in Bithynia and Asia and even Syria. From wherever, in fact, Roman generals had passed by. A few taught, but many were resident scholars, creating for their Roman patrons an air of culture, in the same way as did the laid-out gardens with their covered walks for philosophical discussion among bronzes images of gods, mythological figures, philosophers, and kings. Greeks in Rome accommodated themselves to this selective appropriation of their culture. The prefaces of a number of Greek works composed in this period praise the generosity of their Roman friends. The historian Dionysius of Halicarnassus presented himself as an admirer of the Romans: he regarded the similarities between some Roman and Greek institutions and between the Latin and Greek languages as a sign that Romans were Greek in origin. Gabinius brought Timagenes of Alexandria to Rome as a captive in 55

BC

. Freed and honoured he became for a while the house guest of Augustus himself, but had a reputation as a ferocious critic of Rome. He was reported to have said that the only thing to regret about the many fires suffered by the city was that damaged buildings were always replaced on an even more lavish scale. Eventually he moved on to the home of Asinius Pollio, creator of one of the first public libraries in the capital. Other kidnapped Greeks seem to have adapted more easily. Tyrannio of Amisos, brought back as a captive by Lucullus, was freed and patronized by Pompey. He became a friend and intellectual mentor of Cicero, Caesar, and Atticus and taught grammar and criticism in Rome.

Greeks as well as Romans came to study with him, as they did with the medic Asclepiades of Prusias. Poetry was transformed as well as prose. Parthenius of Nicaea, captured in 73

BC

during a war against Mithridates, was fêted in Rome and inspired a new generation of Latin poets including Cornelius Gallus and Catullus. Latin poetics would remain preoccupied with love poetry and mythological themes throughout the reign of Augustus and beyond. Then there were the visitors, some at least celebrity academics on lecture tours. Poseidonius of Apamea and Artemidorus of Ephesus visited Rome and some of the western provinces giving lectures and gathering material for their histories and geographies. The cumulative influence on Roman culture was enormous.

Greek scholars always needed patrons. During the third and second centuries they found them in the royal courts of Alexandria, Pergamum, and Syracuse, but in the first century they came to Rome. A key part was played by the generation of Romans born in the last years of the second century

BC

. They were the first to make the Bay of Naples their playground—half Las Vegas and half the Left Bank of the Seine—and the first to have travelled in their youth in the Aegean world to study in the ancient cities of Greece. A few even lived there for long periods. Cicero’s friend Titus Pomponius lived in Athens for so long he acquired the nicknamed ‘Atticus’, and Verres fled Cicero’s prosecution to live in exile in Greek Marseilles. Tiberius would spend years on Rhodes during a period when he was out of favour at the court of Augustus. When campaigns in the east, or simply their own wealth, gave them the chance to bring Greek intellectuals to Rome, they grasped the opportunity, just as they filled their boats with Greek bronzes and hunted down copies of rare Greek books. They knew Greek philosophy well enough to identify themselves by school: Cicero the Academic, Caesar the Epicurean, Brutus the Stoic, and so on.

23

They dropped Greek quotations and words into their private letters and conversations.

24

But the clearest sign of their engagement with Greek culture is the determination of some of that generation to create a matching intellectual culture in Latin.

New Classics for a New Empire

Cicero, in his introduction to the

Tusculan Disputations

, is quite explicit that his philosophical works formed part of a conscious project to supply a set of Latin classics in each of the major genres invented by Greeks.

25

Those subjects which deal with the correct way to live—the theory and practice of knowledge—are all part of that body of wisdom that is called philosophy. This I have decided to explain in a work written in the Latin language. Philosophy, to be sure, may be learned from books in Greek, or indeed from Greek scholars themselves. I have always thought that our writers have always proved themselves better than the Greeks, either by finding things out for themselves, or by improving what they have borrowed from them. Obviously this applies only to those fields of study we have decided are worthy of our efforts.

26

The

Tusculan Disputations

form a part of a mass of mainly philosophical writing Cicero produced under the dictatorship of Caesar, when he felt he could neither support nor oppose the man who had enslaved the Republic but spared his own life. Tusculum was the site of Cicero’s philosophically themed retreat; there he entertained younger senators who shared his political and cultural interests. Many of the works he produced are dramatized as dialogues, recalling Plato’s accounts of Socrates debating with his students, but also presenting the Roman elite at their ethical and cultured best. The

Disputations

is in fact dedicated to the same Brutus whose ethics would have such a bloody outcome. Cicero opens by praising the practical morality of the Romans, relative to that of the Greeks, and goes on to argue that although the Greeks may have preceded Romans in many fields, once Romans took up the same pursuits they invariably eclipsed them. Discussion of various genres of Roman poetry moves on to oratory. Cicero’s own work on oratory is presented as a key stage in the creation of a Roman intellectual universe. Now, he says, he will move on to philosophy.

The preface is tendentious in all sorts of ways, and Cicero’s history of Latin scholarship, like Horace’s history of Latin literature contained in a letter ostensibly written for Augustus, has sometimes been taken too seriously. But it is perfectly true that this generation seem to have seen themselves as filling in the gaps in Latin writing and Roman knowledge. Cicero was not the only Latin philosopher. Lucretius’ great Epicurean epic

On the Nature of Things

was nearly complete when he died in 55

BC

. Cornelius Nepos and Atticus were engaged in historical research, trying to establish an absolute chronology for the Roman past, one that would allow key dates in Roman history to be coordinated with world (i.e.: Greek) history. Then there were Varro’s researches into religious antiquities, Roman institutions, the Latin language, and much else. Nigidius Figulus wrote on grammar, on the gods, and science. Nepos wrote biographies of famous Romans. Roman intellectuals seemed sometimes to figure themselves as counterparts of the great

figures of classical Greek literature. Cicero presented himself as the new Demosthenes, and thought of writing a Roman version of the

Geography

of Eratosthenes.

All this activity is sometimes presented as sign of cultural insecurity, but it might just as well be understood as fantastic ambition. Rome had surpassed the Greeks in warfare, why not in literature too? But when Cicero and his collaborators are read carefully it is clear they were not trying to create an alternative, parallel, and self-sufficient intellectual universe. They advocated an eclectic bi-culturalism, a cultivated familiarity with both languages (

utraque lingua

‘in either language’ became almost a catchphrase), and when they described the moral and cultural superiority they sought it was not a

Romanitas

modelled on Hellenism, but

humanitas

, a term that embraces the sense of civilization and common humanity. Roman culture, in other words, had a universalizing mission. Just as Roman houses had Greek and Roman rooms and Roman religion had space for domestic and foreign gods, so the values that the last generation of the Republic proclaimed were bigger than either national culture. That made Roman culture, at least in aspiration, a truly imperial civilization.

Further Reading

A fascinating impression of the curiosity and energy of the Roman elite is conveyed by Elizabeth Rawson’s

Intellectual Life in the Late Roman Republic

(London, 1985). Rawson also wrote what remains the best and most rounded biography of Cicero,

Cicero: A Portrait

(London, 1975). Many of the studies she produced while working on these two books are gathered in her collected papers,

Roman Culture and Society

(Oxford, 1991). Ingo Gildenhard’s

Paideia Romana

(Cambridge, 2007) offers a careful exploration of Cicero’s engagement with the Greeks.

The material setting of Roman Italy is brilliantly evoked in Tim Potter’s

Roman Italy

(London, 1987) and the special culture of the Bay of Naples in John D’Arms’s

Romans on the Bay of Naples

(Cambridge, Mass., 1970). The cultural history of Rome is now the subject of Andrew Wallace-Hadrill’s amazingly wide-ranging

Roman Cultural Revolution

(Cambridge, 2008). At its heart is an examination of how Romans constantly referred to Greek and Italian models as they grew into an imperial culture. Emma Dench’s

Romulus’ Asylum

(Oxford, 2005) explores some of the same terrain, showing the many different routes through which Roman identity was reformulated.

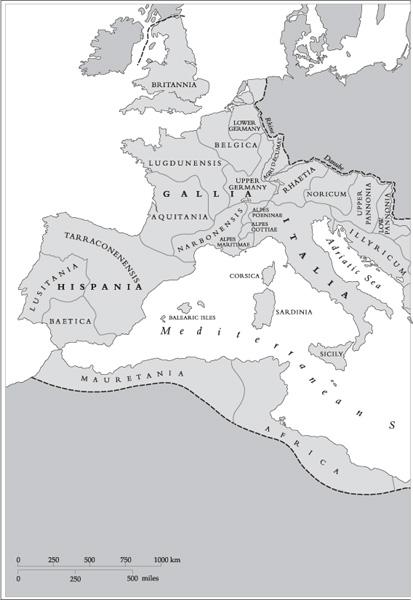

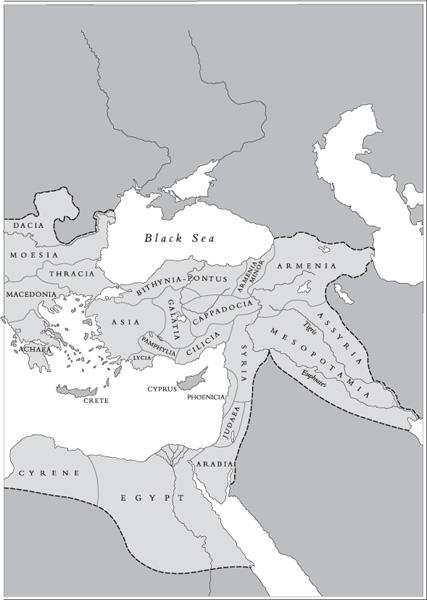

Map 4.

The Roman empire at its greatest extent in the second century

AD

KEY DATES IN CHAPTER XI

31 | Octavian emerges from the Actium campaign as victor of civil wars |

27 | Octavian given the title Augustus by the Senate |

AD | Death of Augustus. The succession of Tiberius |

AD | Assassination of Caius (Caligula). Praetorian Guard impose Claudius as new |

AD | Suicide of Nero leaves no Julio-Claudian heirs |

AD | Year of the Four Emperors, ends with Vespasian establishing the Flavian dynasty |

AD | Assassination of Domitian, succeeded by Nerva |

AD | The reign of Trajan. Major wars against the Dacians and then the Parthians, spectacular building in Rome |

AD | Reign of Hadrian, withdrawal from Mesopotamia |

AD | Reign of Antoninus Pius |

AD | Reign of Marcus Aurelius (jointly with Lucius Verus until 169). Beginnings of increased pressure on northern frontier |

AD | Antonine plague sweeps westwards across empire |

AD | Reign of Commodus |

AD | Assassination of Commodus provokes short civil war, ending in victory of Severus |

AD | Death of Alexander Severus marks the end of Severan dynasty and the beginning of the military crisis of the third century |