Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (163 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

The kidneys have considerable functional reserve meaning that impairment of renal function does not become evident until the equivalent of more than one kidney is lost. This is why it is possible for a person with healthy kidneys to donate one for transplantation.

Table 13.1

lists common signs and symptoms of renal disorders.

Table 13.1

Common signs and symptoms of disorders of the urinary system

| Sign/symptom | Definition and description |

|---|---|

| Oliguria | Urine output less than 400 ml per day |

| Haematuria | Presence of blood in the urine. Leaky glomeruli allow red blood cells to escape from the glomerular capillaries and they cannot be reabsorbed from the filtrate as they are too large. Bleeding in the urinary tract also causes haematuria |

| Proteinuria | Presence of protein in the urine. This is abnormal and occurs when leaky glomeruli allow plasma proteins to escape into the filtrate but they are too large to be reabsorbed |

| Anuria | Absence of urine |

| Dysuria | Pain on passing urine, often described as a burning sensation |

| Glycosuria | Presence of sugar in the urine. This is abnormal and occurs in diabetes mellitus (see p. 227 ) |

| Ketonuria | Presence of ketones in the urine. This is abnormal and occurs in, e.g., starvation, diabetes mellitus |

| Nocturia | Passing urine during the night |

| Polyuria | Passing unusually large amounts of urine |

| Frequency of micturition | Requiring to pass, often small amounts of, urine frequently |

| Incontinence | Involuntary loss of urine |

Glomerulonephritis (GN)

This term suggests inflammatory conditions of the glomerulus, but there are several types of GN and inflammatory changes are not always present. In many cases immune complexes damage the glomeruli. These are formed when antigens and antibodies combine either within the kidney or elsewhere in the body, and they circulate in the blood. When immune complexes lodge in the walls of the glomeruli they often cause an inflammatory response that impairs glomerular function. Other immune mechanisms are also implicated in GN.

Classification of GN is complex and based on a number of features: the cause, immunological characteristics and findings on microscopy. Microscopic distinction is based on:

•

the extent of damage:

–

diffuse

: affecting all glomeruli

–

focal

: affecting some glomeruli

•

appearance:

–

proliferative

: increased number of cells in the glomeruli

–

membranous

: thickening of the glomerular basement membrane.

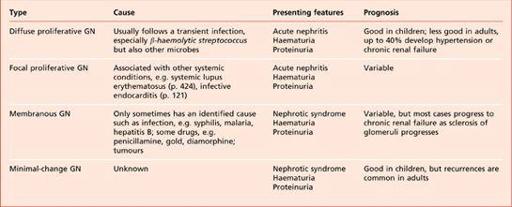

Examples of different types of GN, their causes, features and prognoses are shown in

Table 13.2

.

Table 13.2

Glomerulonephritis: features and prognosis of different types

Effects of glomerulonephritis

These depend on the type and are listed below.

Haematuria

This is usually painless and not accompanied by other symptoms. When microscopic, it may be found on routine urinalysis when red blood cells have passed through damaged glomeruli into the filtrate.

Overt haematuria occurs when there is considerable escape of red blood cells into the renal tubules while smaller amounts give urine a smoky appearance.

Asymptomatic proteinuria

This may also be found on routine urinalysis and, at low levels, does not cause nephrotic syndrome. It occurs as protein passes through damaged glomeruli into the filtrate.

Acute nephritis

This is characterised by the presence of:

•

oliguria (<400 ml urine/day in adults)

•

hypertension

•

haematuria

•

uraemia (

p. 346

).

Loin pain, headache and malaise are also common.

Nephrotic syndrome

(See below.)

Chronic renal failure

This occurs when nephrons are progressively and irreversibly damaged after the renal reserve is lost.

Nephrotic syndrome

This is not a disease in itself but is an important feature of several kidney diseases. The main characteristics are:

•

marked proteinuria

•

hypoalbuminaemia

•

generalised oedema

•

hyperlipidaemia.

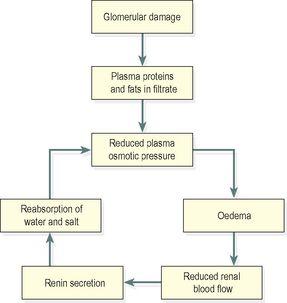

When glomeruli are damaged, the permeability of the glomerular membrane is increased and plasma proteins pass through into the filtrate. Albumin is the main protein lost because it is the most common and is the smallest of the plasma proteins. When the daily loss exceeds the rate of production by the liver there is a significant fall in the total plasma protein level. The consequent low plasma osmotic pressure leads to widespread oedema and reduced plasma volume (see

Fig. 5.61, p. 118

). This reduces the renal blood flow and stimulates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system, causing increased reabsorption of water and sodium from the renal tubules. The reabsorbed water further reduces the osmotic pressure, increasing the oedema. The key factor is the loss of albumin across the glomerular membrane and as long as this continues, the vicious circle is perpetuated (

Fig. 13.24

). Levels of nitrogenous waste products, i.e. uric acid, urea and creatinine, usually remain normal. Hyperlipidaemia, especially hypercholesterolaemia, also occurs but the cause is unknown.

Figure 13.24

Stages of development of nephrotic syndrome.

Nephrotic syndrome occurs in a number of diseases. In children the most common cause is minimal-change glomerulonephritis. In adults it may complicate:

•

most forms of glomerulonephritis

•

diabetic nephropathy (see below)

•

systemic lupus erythematosus (

p. 424

)

•

infections, e.g. malaria, syphilis, hepatitis B

•

drugs, e.g. penicillamine, gold, captopril, phenytoin.

Diabetic nephropathy

Renal failure is the commonest cause of death in young people with diabetes mellitus (

p. 227

) and is more common if hypertension and severe, long-standing hyperglycaemia are present. Diabetes causes damage to large and small blood vessels throughout the body, although the effects vary considerably between individuals. In the kidney, these are known collectively as

diabetic nephropathy

or

diabetic kidney

and include:

•

progressive damage of glomeruli, proteinuria and nephrotic syndrome

•

ascending infection leading to acute pyelonephritis, sometimes complicated by renal papillary necrosis

•

atheroma (see

Ch. 5

) of the renal arteries and their branches leading to renal ischaemia and hypertension

•

chronic renal failure.

Hypertension and the kidneys

Hypertension can be the cause or the result of renal disease. Essential and secondary hypertension (

p. 125

) both affect the kidneys when there is renal blood vessel damage, causing ischaemia. The reduced blood flow stimulates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (see

Fig. 13.14

), raising the blood pressure still further.

Essential hypertension

Benign hypertension

This causes gradual and progressive damage to the glomeruli, which may lead to renal failure after the renal reserve has been lost or to malignant hypertension.

Malignant hypertension

This causes arteriolosclerosis which spreads to the glomeruli with subsequent destruction of nephrons, leading to a further rise in blood pressure and a variable degree of renal impairment in most people. In a few people there are more serious effects; increased permeability of the glomeruli allows escape of plasma proteins and red blood cells into the filtrate causing proteinuria and haematuria, which may progress to renal failure.

Secondary hypertension

This is caused by long-standing kidney diseases and may lead to chronic renal ischaemia, worsening hypertension and renal failure.

Acute pyelonephritis

This is acute bacterial infection of the renal pelvis and calyces, spreading to the kidney substance causing formation of small abscesses. The infection may travel up the urinary tract from the perineum or be blood-borne. It is accompanied by fever, malaise and loin pain.

Ascending infection

Upward spread of microbes from the bladder (see cystitis,

p. 349

) is the most common cause of this condition. Abnormal reflux of infected urine into the ureters when the bladder contracts during micturition predisposes to upward spread of infection to the renal pelves and kidney substance. Normally the relative positions of the ureters and bladder (

Fig. 13.17

) prevents access of microbes into the kidneys.

Blood-borne infection

The source of microbes may be from septicaemia or elsewhere in the body, e.g. respiratory tract infections, infected wounds or abscesses. Due to their large blood flow (20% of cardiac output) the kidneys are susceptible to infection by blood-borne microbes.

Pathophysiology

When the infection spreads into the kidney tissue it causes suppuration and destruction of nephrons. The prognosis depends on the amount of healthy kidney remaining after the infection subsides. Necrotic tissue is eventually replaced by fibrous tissue but there may be some hypertrophy of healthy nephrons. There are a number of outcomes: healing, recurrence, especially if there is a structural abnormality of the urinary tract, and reflux nephropathy. Perinephric abscess and papillary necrosis are complications, usually if the condition is untreated.

Reflux nephropathy

Previously known as chronic pyelonephritis, this is almost always associated with reflux of urine from the bladder to the ureter allowing spread of infection upwards towards the kidneys. A congenital abnormality of the angle of insertion of the ureter into the bladder predisposes to reflux of urine, but it is sometimes caused by an obstruction that develops later in life. Progressive damage to the renal papillae and collecting ducts leads to chronic renal failure and concurrent hypertension is common.