Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (166 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Solid tumours

These are all malignant to some degree. At an early stage the more malignant and solid tumours rapidly invade the bladder wall and spread in lymph and blood to other parts of the body. If the surface ulcerates there may be haemorrhage and necrosis.

Urinary incontinence

In this condition normal micturition (

p. 341

) is affected and there is involuntary loss of urine. Several types are recognised.

Stress incontinence

This is leakage of urine when intra-abdominal pressure is raised, e.g. on coughing, laughing, sneezing or lifting. It usually affects women when there is weakness of the pelvic floor muscles or pelvic ligaments, e.g. after childbirth or as part of the ageing process. It occurs physiologically in young children before bladder control is achieved.

Urge incontinence

Leakage of urine follows a sudden and intense urge to void and there is inability to delay passing urine. This may be due to a urinary tract infection, calculus, tumour or overactivity of the detrusor muscle.

Overflow incontinence

This occurs when there is overfilling of the bladder and may be due to:

•

retention of urine due to obstruction of urinary outflow, e.g. enlarged prostate gland or urethral stricture, or

•

a neurological abnormality affecting the nerves involved in micturition, e.g. stroke, spinal cord injury or multiple sclerosis.

The bladder becomes distended and when the pressure inside overcomes the resistance of the external urethral sphincter, urine dribbles from the urethra. The individual may be unable to initiate and/or maintain micturition.

For a range of self-assessment exercises on the topics in this chapter, visit

www.rossandwilson.com

Section 4

Protection and survival

CHAPTER 14

The skin

The skin

354

Structure of the skin

354

Functions of the skin

357

Wound healing

359

Disorders of the skin

362

Infections

362

Non-infective inflammatory conditions

362

Pressure ulcers

363

Burns

363

Malignant tumours

364

ANIMATION

14.1

Burns

363

The skin

Learning outcomes

After studying this section you should be able to:

describe the structure of the skin

explain the principal functions of the skin

compare and contrast the processes of primary and secondary wound healing.

The first part of this chapter explores the structure and functions of the skin, which is also known as the integumentary system. The second section considers common conditions that affect the skin. The skin completely covers the body and is continuous with the membranes lining the body orifices. It:

•

protects the underlying structures from injury and from invasion by microbes

•

contains sensory (

somatic

) nerve endings of pain, temperature and touch

•

is involved in the regulation of body temperature.

Structure of the skin

The skin is the largest organ in the body and has a surface area of about 1.5 to 2 m

2

in adults and it includes glands, hair and nails. There are two main layers: the epidermis and the dermis.

Between the skin and underlying structures is the subcutaneous layer composed of areolar tissue and adipose (fat) tissue.

Epidermis

The epidermis is the most superficial layer of the skin and is composed of

stratified keratinised squamous epithelium

(see

Fig. 3.13, p. 35

), which varies in thickness in different parts of the body. It is thickest on the palms of the hands and soles of the feet. There are no blood vessels or nerve endings in the epidermis, but its deeper layers are bathed in interstitial fluid from the dermis, which provides oxygen and nutrients, and drains away as lymph.

There are several layers (strata) of cells in the epidermis which extend from the deepest

germinative layer

to the most superficial

stratum corneum

(a thick horny layer) (

Fig. 14.1

). The cells on the surface are flat, thin, non-nucleated, dead cells, or

squames

, in which the cytoplasm has been replaced by the fibrous protein

keratin

. These cells are constantly being rubbed off and replaced by cells that originated in the germinative layer and have undergone gradual change as they progressed towards the surface. Complete replacement of the epidermis takes about a month.

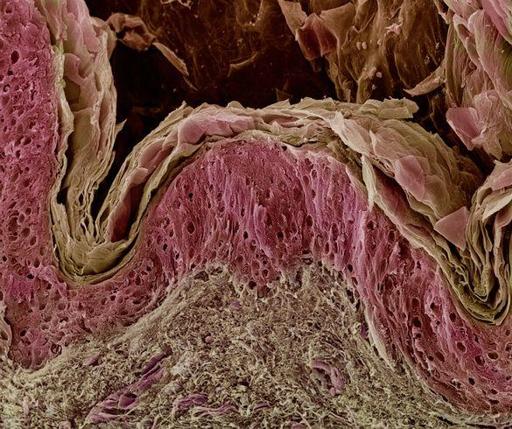

Figure 14.1

Coloured scanning electron micrograph of the skin showing the superficial stratum corneum (pale brown), above the lower layers of the epidermis (pink) and the dermis (grey brown).

The maintenance of healthy epidermis depends upon three processes being synchronised: