Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (182 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Inferior conchae

Each concha is a scroll-shaped bone, which forms part of the lateral wall of the nasal cavity and projects into it below the middle concha. The superior and middle conchae are parts of the ethmoid bone. The conchae collectively increase the surface area in the nasal cavity, allowing inspired air to be warmed and humidified more effectively.

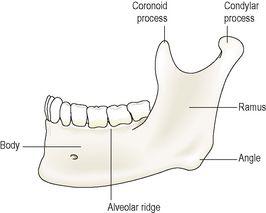

Mandible (lower jaw bone) (

Fig. 16.17

)

This is the lower jaw, the only movable bone of the skull. It originates as two parts that unite at the midline. Each half consists of two main parts: a

curved body

with the

alveolar ridge

containing the lower teeth and a

ramus

, which projects upwards almost at right angles to the posterior end of the body.

Figure 16.17

The left mandible.

Lateral view.

At the upper end the ramus divides into the

condylar process

which articulates with the temporal bone to form the

temporomandibular

joint (see

Fig. 16.12

) and the

coronoid process

, which gives attachment to muscles and ligaments that close the jaw. The point where the ramus joins the body is the

angle

of the jaw.

Hyoid bone

This is an isolated horseshoe-shaped bone lying in the soft tissues of the neck just above the

larynx

and below the

mandible

(see

Fig. 10.4

,

p. 236

). It does not articulate with any other bone, but is attached to the styloid process of the temporal bone by ligaments. It supports the larynx and gives attachment to the base of the tongue.

Sinuses

Sinuses containing air are present in the sphenoid, ethmoid, maxillary and frontal bones. They all communicate with the nasal cavity and are lined with ciliated mucous membrane. They give resonance to the voice and reduce the weight of the skull, making it easier to carry.

Fontanelles of the skull (

Fig. 16.18

)

At birth, ossification of the cranial sutures is incomplete. Where three or more bones meet there are distinct membranous areas, or

fontanelles

. The two largest are the

anterior fontanelle

, not fully ossified until the child is 12 to 18 months old, and the

posterior fontanelle

, usually ossified 2 to 3 months after birth. The skull bones do not fuse earlier to allow for moulding of the baby’s head during childbirth.

Functions of the skull

The various parts of the skull have specific and different functions:

•

The

cranium

protects the delicate tissues of the brain.

•

The

bony eye sockets

provide the eyes with some protection against injury and give attachment to the muscles that move the eyes.

•

The

temporal bone

protects the delicate structures of the ear.

•

The sinuses in some face and skull bones give resonance to the voice.

•

The bones of the face form the walls of the posterior part of the nasal cavities and form the upper part of the air passages.

•

The

maxilla

and the

mandible

provide alveolar ridges in which the teeth are embedded.

•

Chewing of food is performed by the mandible, controlled by muscles of the lower face.

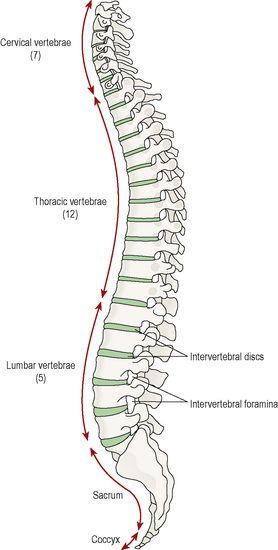

Vertebral column (

Fig. 16.19

)

There are 26 bones in the vertebral column. 24 separate vertebrae extend downwards from the occipital bone of the skull; then there is the

sacrum

, formed from five fused vertebrae, and lastly the

coccyx

, or tail, which is formed from between three to five small fused vertebrae. The vertebral column is divided into different regions. The first seven vertebrae, in the neck, form the cervical spine; the next twelve vertebrae are the thoracic spine, and the next five the lumbar spine, the lowest vertebra of which articulates with the sacrum. Each vertebra is identified by the first letter of its region in the spine, followed by a number indicating its position. For example, the topmost vertebra is called C1, and the third lumbar vertebra is called L3.

Figure 16.19

The vertebral column.

Lateral view.

The movable vertebrae have many characteristics in common, but some groups have distinguishing features.

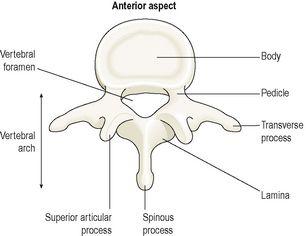

Characteristics of a typical vertebra (

Fig. 16.20

)

Figure 16.20

A lumbar vertebra showing the features of a typical vertebra

– viewed from above.

The body

This is the broad, flattened, largest part of the vertebra. When the vertebrae are stacked together in the vertebral column, it is the flattened surfaces of the body of each vertebra that articulate with the corresponding surfaces of adjacent vertebrae. However, there is no direct bone-to-bone contact since between each pair of bones is a tough pad of fibrocartilage called the intervertebral disc. The bodies of the vertebrae lie to the front of the vertebral column, increasing greatly in size towards the base of the spine, as the lower spine has to support much more weight than the upper regions.

The vertebral (neural) arch

This encloses a large

vertebral foramen

. It lies behind the body, and forms the posterior and lateral walls of the vertebral foramen. The lateral walls are formed from plates of bone called

pedicles

, and the posterior walls are formed from

laminae

. Projecting from the regions where the pedicle meets the lamina is a lateral prominence called a

transverse process

, and where the two laminae meet at the back is a process called the

spinous process

. These are the bony prominences that can be felt through the skin along the length of the spine. The neural arch has four articular surfaces: two articulate with the vertebra above and two with the one below. The vertebral foramina form the vertebral (neural) canal that contains the spinal cord.

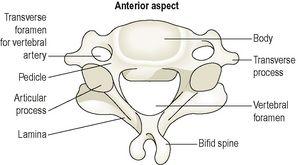

Region-specific vertebral characteristics

Cervical vertebrae (

Fig. 16.21

)

These are the smallest vertebrae. The transverse processes have a foramen through which a vertebral artery passes upwards to the brain. The first two cervical vertebrae, the

atlas

and the

axis

, are atypical.

Figure 16.21

A cervical vertebra, showing typical features

– viewed from above.

The first cervical vertebra, the

atlas

, is the bone on which the skull rests. Below the atlas is the

axis

, the second cervical vertebra (C2).

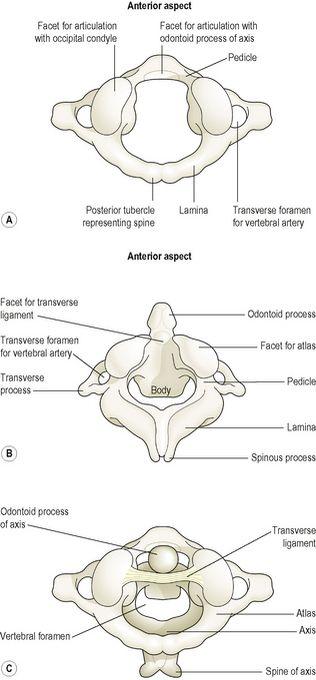

The atlas (

Fig. 16.22A

) is essentially a ring of bone, with no distinct body or spinous process, although it has two short transverse processes. It possesses two flattened facets that articulate with the occipital bone; these are condyloid joints (

p. 404

) and they permit nodding of the head.

Figure 16.22

The upper cervical vertebrae

– viewed from above.

A.

The atlas.

B.

The axis.

C.

The atlas and axis in position showing the transverse ligament.

The axis (

Fig. 16.22B

) sits below the atlas, and has a small body with a small superior projection called the

odontoid process

(also called the dens, meaning tooth). This occupies part of the posterior foramen of the atlas above, and is held securely within it by the transverse ligament (

Fig. 16.22C

). The head pivots (i.e. turns from side to side) on this joint.