Sacred Trash (31 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

B

orn in the first year of that century, Goitein had also—by the time he reckoned with the chill of cold war Budapest and the heat of war-torn Jerusalem, 1948—witnessed enough bloody history, Jewish and general, to make him seriously doubt the whole human race. This did not distinguish him from other members of his generation, though he was, by nature and according to those who knew him well, a pessimist, albeit a forward-looking and phenomenally enterprising pessimist. Having lived through all he’d lived through—what he would describe much later as “the heartbreak, horror and wrath … of so much human misery and degradation”—he might easily have seen in that diminished heap of Hungarian fragments nothing but a sign of woes past and still to come: further proof, if any were needed, that the Jews were congenitally condemned to cycle through an endless Möbius strip of “pain and piety,” and this legacy destined to be ground into dust. Twenty years before Goitein reached Budapest, this “lachrymose” approach to Jewish history had been recognized, named—and challenged—by the eminent social historian Salo Baron, who saw in the works of earlier Jewish chroniclers a distorting tendency to overemphasize the place of suffering in accounts of their people’s past. “Surely,” Baron wrote in one of his most famous essays, published in 1928, “it is time to … adopt a view more in accord with historic truth.”

For Baron, historic truth meant the record of what was, seen as grand demographic, economic, and communal themes that emerged slowly, almost geologically, over centuries. For Goitein, it meant descent into thousands and thousands of discrete particulars, grounded in the grittiest

minutiae of daily life and language, and their eventual deployment in a larger frame. (Goitein invented a term to describe his work, calling himself an “interpretive sociographer,” one who describes a culture by means of its texts.) The two visions were distinct yet connected in spirit, and, Goitein’s pessimism notwithstanding, he would in time turn that “lachrymose conception of Jewish history” on its mournful head—not through polemic, but with his steady and even compulsive emphasis on a brimming history of

life.

As he set out to begin writing that history, his excitement at the vividness of these weathered texts only grew. In one of his first published articles about the India trade—which Goitein called the “backbone” of medieval international commerce and which was the first subject he took up when he began his Geniza research—he described the thrill of holding in his hands these globe-trotting, thousand-year-old documents. Sailing with the merchants from India to Arabia to East Africa, then traveling across the desert and back on a boat down the Nile, they had finally made their way to Fustat, where they landed in the Geniza—and then crossed other seas to libraries in Europe and America, where Goitein sat and peered at them through his sensible mid-twentieth-century horn-rimmed glasses.

But what would he do with this literal and figurative sea of script? How could he begin to make sense of it? As he evolved a system for working with these letters and lists—whether elegantly calligraphed scrolls copied by trained scribes, or hastily scrawled scraps that the merchants themselves had dashed off on deck as their ships pulled out of harbor—Goitein proved himself a master pointillist with a keen ability to grasp, perhaps even more fully than Goldziher could, the allure of the micro

and

the macro, and the cosmos each implied. He knew that in order to prepare the work he had conceived as his “India Book”—a collection of documents concerning these North African Jewish traders, whose business drew them east—it would not be enough to pluck out and carefully read a handful of texts; rather, he would need to comb through enormous

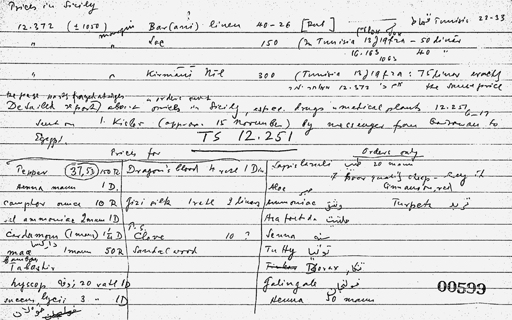

tracts of Geniza documents to find all the letters, court records, and business accounts relevant to the theme, and only then proceed with parsing. By 1954 and the publication of his “preliminary report” on the subject, he had already surveyed all the known documentary contents of eleven Geniza collections on four continents; he’d copied the contents of hundreds of fragments by hand and begun the laborious process of deciphering, translating, and annotating them. Tools, dyes, drugs, perfumes, utensils, articles of clothing—the names of these medieval things were often obscure to even a highly knowledgeable and philologically savvy modern reader like Goitein. So it was that he also went about fashioning a “card index of technical terms,” as if he were compiling a dictionary—unpacking the roots and lexical implications of the merchants’ words themselves for clues to the nature of these garments, vessels, and potions.

Meanwhile, like those traders, he too had set sail from a Mediterranean port as, in 1957, he accepted a regular position at the University of Pennsylvania, and, with a certain heaviness of heart but an extremely clear sense of purpose, left Israel and its multiple distractions (and minuscule research budgets) behind, turning himself over—when he wasn’t teaching—almost exclusively to work on the Geniza. As he was beginning to consider the prospect of widening the lens of his research both methodologically and geographically and starting to reckon with the contents of those unsorted crates in the Cambridge library attic,

chance once again played a part: an offer to write a more general book for an American publisher arrived, and “this decided the matter,” as he wrote later. “I was off India and on the Mediterranean.”

From his first contact with the Fustat documents, Goitein had understood that all the Geniza’s bits and shards would be next to useless unless placed into meaningful relation and somehow glued back together. This refusal to simply settle for one part of a larger whole, this need for connection—between the tiny detail and the big picture, Judaism and Islam, East and West, past and present—would be the force that propelled and inspired him to labor doggedly for the next three decades. His typed research reports from this time refer to “The Cairo Geniza Documents Project,” as though he were the head of a large, lab-coated team building the bomb or mapping the genome. Setting out to create a mammoth collection of thousands of index cards, photostats, and transcriptions that he came to call his “Geniza Lab(oratorium),” he apportioned different parts of the work to a small group of graduate students; at this early stage he envisioned an eight-volume collection of texts to be brought out in twelve years, under the names of these various “workers.” (This was his word.) Yet during this period he labored mostly alone, and the devotion he displayed was as ecclesiastical as it was scientific. And as the project evolved in shape and emphasis, his collaborators faded out of the picture—though he would still insist, as Schecter had, that “a whole generation of scholars will be needed to do this job, each working in a specialized field.” Rather comically, he considered his own nearly superhuman undertaking just a preliminary “inventory” of the documentary Geniza. Making gradual pilgrimages to every Geniza collection throughout the world—he referred to Cambridge as “Mecca”—and attempting to reckon in the most exacting manner with all the nonliterary material contained there, he became a kind of Geniza-divine, dedicated with monastic fervor to his vocation.

“I’ve completely stopped living and become the ‘Genizer,’ ” he scribbled in his diary at around the time he made the switch from “India” to

“the rest,” as he put it. And what was “the rest”? He called it

A Mediterranean Society.

T

he Geniza was, in Goitein’s view, a massive and “erratic” repository of texts that offered “a true mirror of life, often cracked and blotchy, but very wide in scope and reflecting each and every aspect of the society that originated it. Practically everything for which writing was used,” he enthused, “has come down to us.” Fording through this sprawl of disparate documents, Goitein was able to reconstruct in vital fashion and often astonishing detail everything from the nature of the medieval Mediterranean postal service to the Tuesday and Friday distribution of free bread to Fustat’s Jewish poor to the practice of issuing letters of payment, remarkably similar to modern checks. (As Goitein discovered, one twelfth-century Fustat dweller wrote twenty such checks in a single month alone, each inscribed with the Hebrew word for truth,

emet—

also an abbreviation for Psalms 85:12, “Truth springs out of the earth,” a rough medieval precursor to “for deposit only.”) He surveyed with the same unflagging rigor nine-hundred-year-old attitudes toward messianism, remarriage, homosexuality, foreign travel, and pigeon-racing, and plumbed ancient correspondence and business accounts for clues about excommunication, social drinking, the price of flax, the Judeo-Arabic terminology for so-called sweating sickness, the total absence in this older Middle Eastern world of the Bar Mitzva ritual, and the prevalence in the same context of good, hot take-out food.

The bracelets and pendants, wimples and robes, silver spoons and sofas of the time were conjured by Goitein in all their subtle texture.

Colors in particular are enumerated with fanatical precision in the documents, and he was zealous about getting each tint right, describing partridge-eye-hued and chickpea-patterned silks alongside linens the shades of honey, lead, cream of tartar, gazelle’s blood, asparagus, pomegranate, and pistachio. And this “color intoxication” was, he reported, shared by the sexes: the veils that covered the women when they went outdoors were shed at home to reveal a “gorgeous variety of colorful robes,” while “medieval males … must have looked like tropical singing birds.” And such vibrancy wasn’t just a matter of clothing: as he closely read wills, estate inventories, and especially trousseau lists (handwritten accounts of all the pretty and practical things that Jewish brides brought with them into marriage, and which served as a tactile kind of insurance in case of divorce, widowhood, or desertion), he was also able to see—and unfurl for readers—the spectacular tapestry of medieval Mediterranean culture at large.

In this relatively open “religious democracy” Jews were free to practice nearly all the professions, from dyer to stucco worker to banker to phlebotomist to cheese maker to clerk to specialist in carp pickles. They could and did enter into close business partnerships with Muslims and Christians, and lived in any part of town they pleased. “The Geniza reveals a situation very similar to that prevailing today in the United States,” he wrote in the mid-1960s, linking, as he often did, his own present to the past of Fustat. “There were many neighborhoods predominantly Jewish, but hardly any that were exclusively so.” No ghetto existed in that setting, and members of different communities and religions often owned or rented apartments in the very same building. In Goitein’s estimation, even in the more heavily Jewish areas of Fustat, at least half the Jews had gentile neighbors.

The “loosely organized and competitive” society reflected in the Geniza documents reminded Goitein of the “vigorous, free-enterprise society” of the United States, while the American obsession with “endless fund-raising campaigns and all that goes with them, … [the] general

involvement in public affairs and deep concern (or lip service, as the case may be) for the underdog” also had their medieval Egyptian antecedents.

“We do not,” he wrote, “wear turbans here; but, while reading many a Geniza document one feels quite at home.”

The “classical Geniza period,” Goitein announced on the opening pages of the very first volume of

A Mediterranean Society,

was characterized by “relative tolerance and liberalism,” and he closed the circle, five volumes, some three thousand pages, and several decades later by praising this “civilized world, of people who knew how to behave, who were considerate, paying proper attention to their fellowmen.” That said, he was careful not to blur too casually the boundaries between medieval and modern sensibilities: “Before characterizing the Jewish community in Geniza times as a ‘religious democracy,’ I hesitated very much,” he wrote, years after first coining the term. “I use the word ‘religious’ in its Latin sense of ‘binding.’ It was a democracy bound by divine law. This means that there were certain tenets, injunctions, and practices that could not be questioned because they were laid down in the Torah or Talmud. That democracy had no ‘law makers,’ only authorized interpreters of a law that was freely recognized by everyone.”