Sacred Trash (32 page)

Authors: Adina Hoffman

Neither did he paint an overly idealized picture of that time and place. As

dhimmi,

or “protected” citizens, the Jews and Christians of the Fatimid (and later Ayyubid) empires were—from the age of nine and without exception—each expected to pay a yearly poll tax. For all but the most well-off, the charge was onerous. Goitein described the “season of the tax,” when payment was due, as a time of “horror, dread, and misery.” And there were occasional periods—under the rule of the psychotic caliph al-Hakim, for instance—when the

dhimmi

were harshly persecuted. (Like the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem, the Ben Ezra synagogue was demolished during al-Hakim’s reign, around 1012, and rebuilt afterward: the Geniza chamber dates, it would seem, from the time after its reconstruction.) It is clear from Goitein’s rendering

, however, that such bald oppression was the exception, not the rule; likewise, the regular payment of the poll tax was, all things considered, a small price to pay for the power it granted these prosperous, Arabic-speaking Jews to more or less govern their own communities and practice their religion as they saw fit. A certain deference to Islam and to Muslims was expected among those the Prophet Muhammad had dubbed the “People of the Book” (non-Muslims to whom scripture had been divinely revealed)—but for the most part, the Jews of this Mediterranean society fared much better than they did under Christian rule; they were left to pray, work, study, eat, marry, divorce, dress (in most circumstances), and even hand down legal judgment as they themselves determined.

Apart from the broader social synthesis he coaxed from the heaps of raw material he’d gathered over decades, Goitein was able to limn striking portraits of some of the individuals who made up that Mediterranean society. His fascination with a huge array of the “characters” who formed this cast of actual thousands was periscopic, swiveling to take in people like the previously overlooked—though thoroughly unforgettable—“Wuhsha the Broker,” about whom, Goitein’s family recalls, he would often gossip, as though he had just bumped into her that morning.

Known in the documents by her nickname—which Goitein translates as “Désirée” or “Object of Yearning,” though the three-letter Arabic root also implies “Wild One”—Wuhsha (whose real name was Karima, the daughter of Ammar) turns up more often than any other woman in the papers once held in the Ben Ezra synagogue. A rich, eleventh-century divorcée with a flourishing business as a sort of private pawnbroker, she also had a (Jewish) lover named Hassun, and bore him a son out of wedlock.

Despite the patriarchal nature of Geniza society, and the fact that the economic lives of its women were, as a general rule, constricted, Wuhsha seems to have been perfectly able to take care of herself. Various weathered legal documents give us a strong sense of Wuhsha the shrewd businesswoman

, Wuhsha the hard-nosed wheeler-dealer. But in many respects the most interesting fragments related to Wuhsha are those that concern her private life—or the place where her private life became very public indeed.

A single page remains of a remarkable court deposition, written after Wuhsha’s death. Her son, Abu Sa‘d, was now grown and apparently eager to marry; in order to do so, he had to prove that he was not the product of an incestuous relationship, and so witnesses were summoned to attest to his paternity. The first man described how he had been sitting one day, years before, with Hillel ben Eli—a well-known scribe of the time, who had written Wuhsha’s trousseau list, and whom Goitein describes as her confidant. Wuhsha turned to Hillel, in urgent need of advice. “I had an affair with Hassun and conceived from him,” she explained. (The words for “I had an affair,”

waqat ma‘,

mean literally “I fell with,” though as Goitein explains, they might be translated as “I got into a quagmire with” or, with a slightly altered preposition and more bluntly, “I slept with.”) She was afraid that Hassun—who was a Palestinian refugee, so to speak, from Ascalon, which was under threat of Crusader invasion, and who Goitein suspects already had a wife there—would deny being the father of her child.

Her friend Hillel seems to have been unfazed by this news of Wuhsha’s dalliance. Without batting a scribal eyelid, he advised her to set up a trap in which several witnesses would surprise Hassun in Wuhsha’s apartment. (For a man to relax alone like that in the home of an unmarried woman could—to modesty-minded medievals—mean only one shameful thing.) By doing so she would be able to confirm a sexual relationship with Hassun and, at least by circumstantial evidence, prove him the would-be deadbeat dad.

The story of Wuhsha’s little sting operation is repeated in the document by a ritual slaughterer who lived downstairs from her and who described how she had invited a couple of other neighbors to come up to her place “for something.” He explains: “The two went up with her and

found Hassun sitting in her apartment and …” the badly damaged manuscript gives out here, but picks up with the telling “ … wine and perfumes …” and breaks off again, suggestively.

Others were less understanding than Hillel and the neighbors. According to testimony provided in the same document, Wuhsha—whose unorthodox sexual situation was apparently no secret around town—had put in an appearance at the Babylonian synagogue on Yom Kippur, and the head of the community had noticed her … and promptly kicked her out.

However mortifying it must have been for Wuhsha to be expelled from synagogue on the holiest day of the year, she had her pride—and she also had the last laugh. In her will, written by the same Hillel ben Eli, she made a point of leaving an equal amount of money to each of the synagogues of Fustat, including the Babylonians who had given her the boot. The funds were earmarked “for oil so that people may study at night.” And while she piously promised a respectable 10 percent of her estate to charity, she also stipulated that “not one penny” should go to Hassun, and she provided lavishly for her own funeral: At a time when two dinars could support a lower-middle-class family for a month, she set aside a full fifty dinars for this posthumous extravaganza since “the socially ostracized Wuhsha wanted,” according to Goitein, “to show off and prove to everyone what a great woman she was.”

Finally, though, it was Wuhsha’s son, Abu Sa‘d, then still a child, who was her main concern: she left him a good deal of money, as well as “all I possess in cash and kind, in rugs and carpets,” and she made provisions for his education. She named a teacher who should instruct him about the Bible and prayer book “to the degree it is appropriate that he should know them,” and she set aside funds for the teacher’s salary, ordering that he be given “a blanket and a sleeping carpet so that he can stay with” the boy. Wuhsha may have been unusual for her time, but she was still a Jewish mother.

A

t the very opposite end of the Egyptian social scale was the tortured figure of Abraham Maimonides (1186–1237), with whom Goitein chose to bring

A Mediterranean Society

to its melancholy close. Although time has not been especially kind to Abraham and though he faced serious controversy in his day, this “perfect man with a tragic fate” was much more than the only son of the renowned Moses Maimonides. Abraham, in Goitein’s words, “stood for everything regarded as praiseworthy in the society described in this book.” He was also, as several other commentators have noted, a figure with whom Goitein himself seems to have identified deeply.

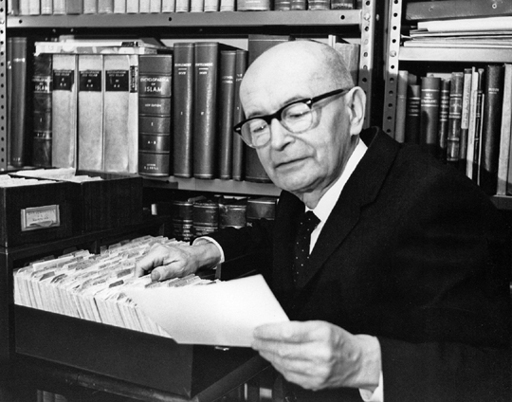

The two had a long history together. In 1936, as a hyper-engaged Hebrew University scholar of Islam, Goitein had been asked to translate a book of Abraham’s responsa—or rabbinic answers to petitioners’ questions—from Judeo-Arabic to Hebrew. “I developed quite a personal affection for him,” Goitein wrote of that early encounter with the scholar, physician, and communal leader known for his blend of humility and firmness, as well as for what his doting father called his “subtle intelligence and kind nature.” Over the course of Goitein’s decades spent in the company of the Geniza materials, he had made the assessment of Abraham’s legacy a kind of pet project, and collected numerous letters and records that pertained to him, as well as more than seventy-five Geniza documents in

Abraham’s own hand—

a prototypically hard-to-read doctor’s hand, as it happens, whose Hebrew letters run together in an almost uninterrupted flow that looks much like Arabic.

Up to Goitein’s final months, in 1985, he had been laboring late into his nights to complete

A Mediterranean Society—

the comprehensive, several-thousand-page work that he continued to refer to as “only a sketch.” He and Theresa had moved to Princeton in 1971, when he retired from teaching and became a long-term member of the Institute for Advanced Study there; he converted the living room of their modest, green clapboard house into his study and the headquarters of his Geniza

Lab, and wrote most of the last three volumes in this quiet suburban setting. While he had proceeded according to a typically punctilious schedule through the first four installments (and continued to publish other books and numerous articles, even as he dashed off or dictated letters by the score, admitting to one correspondent in 1977 that “sometimes I write up to twenty … a day”), the fifth and final volume was, as one of his Princeton colleagues remembered after his death, “the most difficult to conceptualize and write.” No precedent existed in either Islamic or Jewish studies for offering, as Goitein did, a summation of this sort: an extended meditation on the

inner

life of the medieval Mediterranean individual as it was revealed in the Geniza documents. Now, at the twilight of a long, fertile, and intensely varied career, he had chosen to return to the place he’d set out from as a young scholar—to Abraham Maimonides, who represented, in Goitein’s words, “all the best found in medieval Judaism, as it developed within Islamic civilization.”

Like his father before him, the charismatic Abraham had served as Rayyis al-Yahud, the head of the Jews—representative of Egyptian Jewry before the Muslim authorities and the supreme spiritual and secular authority within the community. His political career, though, was not what distinguished him for Goitein. Rather, it was how he “united in a single person three spiritual trends that were usually at odds with each other”: a total mastery of traditional Jewish sources; a “fervor bordering on faith” in the Greek sciences; and greatness as a teacher of religious ethics.

Beyond that, he was a visionary religious reformer, a rationally

minded mystic who was outspoken in his condemnation of the superficial and luxury-loving behavior of so many of his fellow Fustat Jews. As an alternative, Abraham reiterated in detail the laws that bound the Jewish community and proposed various synagogue reforms: the washing of feet before prayer, numerous prostrations, and the lifting of hands heavenward in supplication—as at the mosque. He had also gathered around him a small band of pietistic disciples. Drawing directly from the Sufi teachings that swirled through the Middle Eastern air at the time, he described the virtues of the “special way” or “high paths” to be followed by this elect group and went so far as to praise the rag-wool-wearing, night-vigil-keeping bands of Sufi—that is, Muslim—novices as being truer descendants of the biblical Prophets than the Jews of the age. He longed, it seems, to bring his select band of “Jewish Sufis” together as a community of initiates, dedicated to the ascetic life, the contemplation of secret knowledge, and the striving toward “the arrival at the end of the way, the attainment of the goals of the mystic.”

Yet for all Abraham’s prophetic pronouncements about “high paths,” it was his entanglement in far

lower

matters—in the mundane business of serving as his community’s all-in-one administrator—that emerged from the pile of Abraham-related documents that Goitein unearthed in the Geniza. While Moses Maimonides had been the official head of Egypt’s Jews on and off for just a few years and was known to have “groaned under” the load of this work, his son served in this distracting capacity for his entire adult life, from the age of nineteen until his death at fifty-one.

Goitein found it “appalling” that Abraham was forced to play so many roles at once: he presided as judge at sessions of the Fustat court and penned numerous written responsa to legal questions, many drafts of which turned up in the Geniza. (These Dear Rabbi queries concerned everything from sexual relations with female slaves to the milking of sheep on the Sabbath.) He was, at the same time, chief of welfare services

, responsible for the poor and sick, the widows and orphans of his city: Goitein counted more than fifty orders of payment (salaries, subventions, donations) in Abraham’s own hand from a single year alone. As Geniza letters attest, he managed the hiring and firing of communal personnel and was frequently required to smooth the ruffled feathers of various miffed provincial dignitaries. Besides having to snuff out the rash of political wildfires that flared around his own tenure as Rayyis, he often served as peacemaker, intervening, for instance, in a nasty power struggle between the warring members of a prominent Alexandria family. He also performed weddings and acted as registrar of all Jewish marriages and divorces, and he worked, too, as his own legal proofreader; scribal standards had fallen off by his time, and Goitein discovered court documents that Abraham himself had corrected.