Salem Witch Judge (7 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

In the minds of the Puritan ministers, public punishment of a sinner was a public service. It demonstrated to the community the wages of sin. But many people considered it simply a celebrated spectacle, a chance to skip work and have fun, as a ball game or a parade is regarded today. Twenty-seven years later, at the public execution of another convicted murderer on Boston Common, Samuel rearranged his schedule to give his servant Tom Lamb a day off, “as ’tis promised him,” so Lamb could attend the event and share in the crowd’s “general satisfaction.” During a visit to Cambridge, England, in 1689 Samuel noted that the gallows of that university town was suitably located on “a dale, convenient for spectators to stand all round on the rising ground.”

On March 11 at the Sewall house several blocks from the First Church, Samuel donned his overcoat and headed for the market square, where the First Church was. The size of the gathering crowd amazed him. Standing apart from the mob, Samuel watched men and women shove through the main entrance of the Old Meeting House, as he called the First Church. During a lull he slipped into the church through a side door. Morgan, fresh from jail, stood at the front of the meetinghouse near the pulpit. Iron chains encircled the convicted murderer’s arms, yet he clasped a Bible, making a visual image of a penitent sinner. This was standard during an execution sermon. As much as the Puritans hated “popish” symbols like stained glass and ornate statuary, they understood the power of imagery. Penitents in church sometimes wore sackcloth over their clothes as a symbol of repentance or covered themselves with ashes. These practices had biblical roots. In the Old Testament the prophet Daniel displays sorrow and anguish by wearing sackcloth and ashes. Job sews a garment of sackcloth to wear beside his skin. Humbled by God, he says in chapter 42, “I abhor myself, and repent in dust and ashes.” In Jonah 3:3–10 God sends Jonah to Nineveh to warn the city that God will punish its

sins. In response to this warning the king of Nineveh proclaims a fast and orders his people to cover themselves with sackcloth, “cry mightily to God,” and “turn from” evil and violence. “When God saw what they did, how they turned from their evil way, God repented of the evil which he had said he would do to them; and he did not do it.” The Salem minister John Higginson affirmed in 1686 that sackcloth “signifies the sad afflicted and mournful condition that the churches and witnesses of Christ shall be in.”

Public repentance was essential to Puritan devotional life. Despite the seeming bleakness of the core belief in humanity’s fundamental depravity, Puritan theology always left a door open to sinners. If a sinner would only repent, he might return to grace. The practice of course had biblical roots. The Hebrew word for repentance means “to return” and “to feel sorrow.” The New Testament word for repentance is the Greek metanoia, which means “a change of mind,” “to think again,” or “to see in a new way.” Thus repentance is a change of mind and heart that occurs after the fact. Repentance was so important to Puritans that the question of innocence or guilt became secondary. If a person confessed and seemed to repent, he was given another chance. Repentance might not prevent punishment, but it enabled a sinner to be reconciled with God. If repentance happened in public, as with James Morgan, the community could benefit. Thus the Reverend Mather’s sermon on Morgan’s misbehavior was not only to reform Morgan but also to instruct the crowd.

As Samuel watched the rabble, the Reverend John Eliot approached him. Eliot, who was known as the Indian Apostle because of his commitment to evangelizing Native Americans, was now eighty-one years old. One of Boston’s first and best known ministers, he had arrived in 1631 on the ship carrying Governor John Winthrop’s family. He began preaching at Roxbury the next year. His attentions always honored Samuel, who considered “Mr. Eliot” a mentor.

“Captain Sewall, a crazed woman has caused a panic in the gallery of the meetinghouse,” the ancient minister greeted him, using Samuel’s military title. As a captain of the Ancient and Honorary Artillery Company, Samuel led the troops in their monthly exercises on Boston Common. The crazed woman, later revealed to be the daughter of Morgan’s master, who resented losing her servant, had disrupted the

meeting by crying “Fire!” from the balcony of the meetinghouse. This prompted people to “rush out with great consternation,” according to Eliot, who feared the gallery might fall under the weight of the crowd. Eliot asked Sewall’s permission to move the meeting a block up the road to the larger Third Church.

Sewall consulted with Governor Bradstreet, who had been a member of the Third Church since 1680, and the Reverends Cotton and Increase Mather. All consented to the move, which took an hour to accomplish. In the Third Church, the Reverend Increase Mather led James Morgan, still in chains, to the pulpit. Mather was a tall, thin man with a long, thin face, a prominent nose, and a solemn look due partly to poor eyesight. A serious man, he had a tendency toward depression or, some historians say, manic depression. The experience of partaking in the Lord’s Supper sometimes overwhelmed him with such a sense of God’s generosity to humanity that he was moved to tears. For this execution sermon he had chosen a relevant text, Numbers 35:16: “If he smite him with an instrument of iron, so that he die, he [is] a murderer: the murderer shall surely be put to death.”

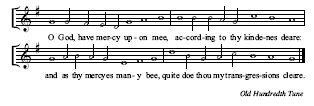

After the lecture the congregation sang the first part of Psalm 51, a song of penitence that calls for deliverance from sin. King David composed this psalm after recognizing, through the interventions of the prophet Nathan, that his behavior with Bathsheba—committing adultery and arranging for her husband to be murdered—was sinful. The story of King David’s growing awareness of his wrongdoing was meant to help turn a sinner toward God. Their Latinate English translation from the biblical Hebrew was the second version of this psalm offered by the Bay Psalm Book.

O God, have mercy upon mee,

according to thy kindenes deare:

and as thy mercyes many bee,

quite doe thou my transgressions cleare.

2 From my perversnes mee wash through,

and from my sin mee purify.

3 For my transgressions I doe know,

before mee is my sin dayly.

4 Gainst thee, thee only sin’d have I,

& done this evill in thy sight:

that when thou speakst thee justify

men may, and judging cleare thee quite.

5 Loe, in injustice shape’t I was:

in sin my mother conceav’d mee.

6 Loe, thou in th’inwards truth lov’d haz:

and made mee wise in secrecie.

7 Purge me with hyssope, & I cleare

shall be; mee wash, & then the snow

8 I shall be whiter. Make me heare

Joy & gladnes, the bones which so

Thou broken hast joy cheerly shall.

9 Hyde from my sins thy face away

blot thou iniquityes out all

which are upon mee any way.

For his final walk from the meetinghouse to the Boston gallows, James Morgan requested the company of the Reverend Cotton Mather. The two men prayed together as they traveled the two rutted blocks to the broad slope of the common, where the gallows stood. The young minister, who is now considered Massachusetts’s most famous Puritan preacher, was then just a promising third-generation legacy, the son and grandson of more famous ministers, with the insecurities attendant on that status.

Cotton Mather’s double surname indicates his dual descent from the founding generation of divines. John Cotton, his mother’s father, was the celebrated English Puritan preacher. In 1633, after the Church of England archbishop, William Laud, suppressed him, John Cotton sailed to Boston, where he was immediately given the plum position of teacher at its First Church. John Cotton died in 1652. Four years later his widow married Richard Mather, the Dorchester minister, who had arrived from England in 1635 after similar persecution for his religious nonconformity. Richard and Sarah Cotton Mather lived together with their younger children in the Cotton house on Cotton Hill, which is now known as Pemberton Hill and faces Boston City Hall. (A brass plaque on the plaza before the John Adams Courthouse marks the site of that house.) Cotton’s daughter Mary married her stepbrother the Reverend Increase Mather in 1662 and nine months later gave birth to Cotton Mather. A brilliant child, he could read and understand Greek and Latin at age eleven, when he was admitted to Harvard College, roughly four years younger than most of his classmates. The summer that eleven-year-old Cotton Mather entered Harvard, Samuel Sewall graduated at twenty-two with a master’s degree in divinity. Four years later, when he was only fifteen, Cotton Mather received an undergraduate degree. In his early twenties he preached often at his father’s church in the North End, and his father ordained him in May of 1685. Now, in 1686, Cotton Mather was just twenty-three. He had a rounder face than his father, a prominent nose, and large, intense, widely spaced eyes. He wore the black preaching gown and skullcap favored by Puritan divines.

A crowd of onlookers followed the minister and the condemned servant, enjoying the spectacle and the anticipation of more. At the gallows Mather and Morgan continued praying for so long that most of the crowd departed for the midday meal. Morgan’s repentance did not prevent his punishment, and at five-thirty James Morgan was finally “turned off,” as Samuel noted that evening in his diary: “The day was comfortable but now, [at] 9 o’clock, rains.”

Although Samuel apparently lost no sleep over Morgan’s soul, he regretted the loss of saintly men and women. Only twenty-four hours after Morgan’s execution Samuel reported that “Father Porter,” who was “acknowledged by all to have been a great man in prayer,” was “laid in the Old Cemetery.”

Hardly a month after Morgan’s execution, the leading men of Boston were again called to punish misbehavior, this time by one their

own. The offender was a young minister, twenty-eight-year-old Thomas Cheever, a son of the Boston schoolmaster, Ezekiel Cheever, whom Samuel and his colleagues knew intimately as the teacher of their sons. Young Cheever preached in Malden, northeast of Cambridge. Townspeople accused him of committing adultery and using obscene language “not fit to be named.” The former involved “shameful and abominable violations of the Seventh Commandment” (“Thou shalt not commit adultery”). The latter, a violation of the Third Commandment (“Thou shalt not take the Lord’s name in vain”), occurred in a public house in Salem.

A group of powerful magistrates and ministers had agreed to sit in justice on this case, as was standard in the Congregational Church. Samuel and his friend and minister, Samuel Willard, of the Third Church, were asked to join this ad hoc church court, and both consented. At four in the morning of April 7, 1686, the two Samuels met at the front gate of Sewall’s house to walk together to the Charlestown ferry. They had no horses because the trip to Malden could be accomplished mostly by water. Before dawn they had crossed the Charles River by ferry and hired another boat to take them up the Mystic River to the Malden River. From the Malden dock they walked to a private house owned by Cornet Henry Green, where the church court would meet.

The court comprised representatives of Boston’s three churches (First, Second, and Third) and several members of the General Court, including Samuel and John Richards, who would later serve with Samuel on the witchcraft court. Several additional men crowded into the parlor of the Green house, including Samuel Parris, a pale man of thirty-two with long brown hair who was considering becoming a minister. Parris wanted to learn about church discipline. A few years hence, in November 1689, Parris would be ordained and installed as the preacher of Salem Village, where he would lead the charge against suspected witchcraft in 1692. Ezekiel Cheever, the father of the accused, had requested permission to be present and was allowed, as befitted his high status. The ministers, teachers, and judges of early New England had intentionally left behind many trappings of life in Old England, yet they had perhaps inadvertently created new versions of aspects of that world. They developed an oligarchy, for instance, in

which the sons of the leading citizens in one generation became the leaders, often the Congregationalist ministers, of the next.

The Reverend James Allen began the meeting of the church council with prayer. Allen, an Oxford-educated Puritan in his early fifties who had sailed to America in 1662 after the Church of England ejected him, had served at Boston’s First Church since 1667. The group quickly chose as its moderator Increase Mather, who commenced to pray. Increase Mather was the rare Harvard-educated Bostonian who had sailed east across the ocean. After taking a master’s in divinity at Trinity College, Dublin, he had returned to Boston in 1661. Since 1664 he had preached twice weekly at the Second Church, as he would do for nearly four decades, often to a congregation of a thousand.

Following a brief debate over procedure, the judges called in young Cheever and several witnesses to his misbehavior. The witnesses recounted what they had observed—adultery and obscene language. Cheever said he was innocent of all the charges: the accounts the court had heard were false. The Reverend Joshua Moody of Boston’s First Church spoke for the council in admonishing Cheever for “grievous” behavior. Moody advised Cheever to repent. Cheever said he could not repent because he was innocent. Moody said he should sleep on the council’s recommendation. That evening, before Samuel Sewall, John Richards, and the Greens’ other houseguests could retire to bed, Increase Mather prayed with them for another hour. Private houses often served as inns, as bed-and-breakfasts do today. Lodging was also available at many public houses, which served as taverns and inns every day except the Sabbath, when they were required to close.