Salem Witch Judge (8 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

Early the next morning Mather prayed over his notes of the proceedings before sending for the accused. Mather told Cheever that the council believed the accusations against him. Cheever replied, “If I ever did violate any of the Commandments, I have no memory of it.”

Angrily the older minister said, “The council, at the request of this church in Malden, declares Thomas Cheever guilty of great scandals, by more than two or three witnesses…. We have cause to fear that he has been too much accustomed to an evil course of levity and profaneness. Also we find that as to some particulars he pretends he does not remember them. Nor,” he emphasized, “have we seen that humble penitential frame in him when before us, that would have become him.”

Repentance, that key ingredient for Puritans, was lacking. A few years later an exemplary Massachusetts minister, Joseph Green, who took the pulpit of Salem Village in the troubled period after the witch trials, enumerated in his diary the steps to living rightly as a Puritan. Repentance was essential to his list.

1. Pray to God in secret…. Pray to God that he would pardon your sins…. Pray to Jesus Christ to pardon you…and save you from hell fire, and from eternal misery….

3. Keep holy the Sabbath day. Do not speak your own words nor think your own thoughts on the Sabbath, but spend the whole day in reading and praying and other holy duties….

5. Remember Death; think much of death; think how it will be on a death bed, whether then you will not wish that you had prayed….

6. Think much of the Day of Judgment, when…all secret sins shall be discovered and shall be punished with eternal burnings….

7. Think…seriously of eternity. Think of those that are in hell, that must abide under all the pain imaginable to eternity, and those that are in heaven shall live in the greatest happiness with God forever….

9. Do not put off your repentance ’til tomorrow; but today while the day of grace lasts give all diligence to secure your souls; for you know not you may be in hell before tomorrow if you defer your repentance.

Sin is a natural consequence of humanity’s fall in both Jewish and Christian traditions. As descendants of Adam and Eve, humans cannot avoid sin. But after sinning must come repentance, turning away from the sin. That is the only way to redemption. At Malden that day the ministers urged Cheever to do what was right. They prayed that he would turn away from his sin and toward God. Cheever refused.

Seeing young Cheever fail to manifest “that repentance which the rule requires,” the Reverend Increase Mather spoke for the council.

“We suspend Mr. Thomas Cheever from the exercise of his ministerial function” and “keep him from the Lord’s Table” for six weeks. In addition to losing his work as a preacher, young Cheever lost his enjoyment of one of the two sacraments of the Congregational Church. Reformed churches had left behind most of the seven Roman Catholic sacraments, preserving only two, baptism and communion. (They called their sacraments ordinances, also to separate themselves from the Catholic Church.) Baptism could be granted to children of the elect in the Puritan church, but communion was reserved for the elect, those people who could convincingly show they were under God’s grace, which Cheever no longer could.

The church council met again six weeks later, this time in Boston, to determine if Cheever could be brought back into communion. Brought before the ministers and judges, Cheever again refused to acknowledge guilt. In response, the council unanimously found him guilty and dismissed him as Malden’s pastor. He would later move east to Rumney Marsh, which is now Revere, and find work as a teacher. The church council also urged a fast day in Malden so the congregation could “humble themselves by fasting and prayer before the Lord.”

Samuel “came home well” from the council meeting in Malden—thanking God in his usual way by noting in his diary “Laus Deo”—but all was not well at home. Little Hull’s seizures were worse. They had grown more frequent in recent weeks. One morning Samuel arose to discover that his now-youngest son had had “a sore fit in the night,” soiling himself and his parents’ bed.

The exact cause of Hull’s convulsions is not clear, although children commonly contracted infections that led to diarrhea, vomiting, high fever, and sometimes seizures. Two of Samuel’s intimates, his brother Stephen and his friend Elisha Hutchinson, had recently lost infant sons who had suffered multiple convulsions, probably due to infections that spread to the brain. Samuel and Hannah’s first two sons had also had febrile convulsions. Baby John’s first two seizures occurred when he was two months old. Asleep in his cradle on Sunday, June 16, 1677, the child “suddenly started, trembled, his fingers contracted, his eyes starting and being distorted.” This prompted his twenty-five-year-old father to ride to Charlestown for the doctor. Two days later the baby had another seizure. Johnny died fifteen months later of unknown causes. Hoping to avoid this result with Sam Jr., in May 1680 Samuel “carried” his almost two-year-old namesake “to Newbury where his grandmother [Sewall] nurses him,…to see if [the] change of air would help him against convulsions.” It was

reasonable to remove a frail child from a crowded port town that received ships bearing sailors who might be infected with smallpox, malaria, typhus, influenza, dysentery, or other scourges. Sam Jr. experienced no seizures while with his grandparents, returned to his parents healthy a year later, and was now approaching his eighth birthday.

Hullie, who still had a serious fit about once a week, nevertheless began to walk and talk. His first word was “apple,” which his grandmother Hull and a servant named Eliza Lane heard him utter in the kitchen on Sunday, February 1, 1686, when he was eighteen months old. This news filled Samuel with hope and joy. In late March, however, Samuel noted that while he was visiting the Reverend Increase Mather at home in the North End, Hull had a “very sore” seizure.

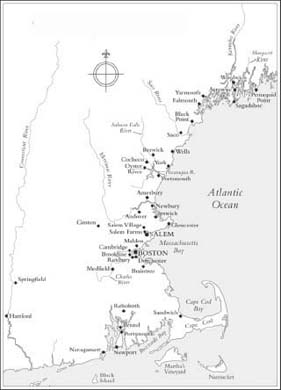

The next week, hoping to cure his fits, Samuel and Hannah decided to send little Hull to stay with his paternal grandparents in Newbury, Samuel’s adopted hometown. Sewall did not set eyes on this region until he was nine, yet he considered himself a “Newbury man.” The region’s hold on him was due, in part, to its landscape. Horses and cattle grazed on fields of salt marsh dotted with haystacks that stretched to the sea. At the shore a slender barrier island, Plum Island, provided protection for mackerel, sea bass, and migratory birds. “Plum Island lies, like a whale aground, / A stone’s toss over the narrow sound,” the nineteenth-century poet John Greenleaf Whittier wrote. “Beyond are orchards and planting lands, / And great salt marshes and glimmering sands.” The hills of Newbury afforded magnificent views of Cape Ann, New Hampshire’s Isles of Shoals, Mount Agamenticus in Maine, and the vast Atlantic. This was a magical world to which Samuel delighted in bringing his children.

Early on April 26, 1686, Samuel and Hannah and their smallest living son set out for Newbury. The driver of their coach was Samuel’s clerk, Eliakim Mather, the Reverend Increase Mather’s nineteen-year-old nephew, who lived with the Sewalls. As the coach headed north through Charlestown, the “chippering” sparrows “proclaimed” to Samuel the arrival of spring. The travelers met Samuel’s brother Stephen at the intersection of the Boston and Cambridge roads. On horseback, he accompanied them to his house in Salem, where they spent the night.

Salem, the largest town on the colony’s North Shore, had been founded by English settlers two years before Boston. The Indians called it Naumkeag, a word for a fishing place, but its English founder, John Endicott, renamed the port town using the Hebrew word for peace. Stephen Sewall, who attended Harvard briefly as a teenager before becoming apprenticed for five years to a Salem merchant, was trusted with various important roles in town. He was the clerk—scribe—of several courts, the register of probate and deeds for Essex County, and a justice of the peace.

Salem was home to not only Samuel’s brother but also many colleagues and friends. Samuel visited often, usually on trips between Boston and Newbury or other North Shore towns. He generally stayed overnight with his brother, who was five years his junior, and Stephen’s twenty-one-year-old wife, Margaret, who were still grieving the death of their first baby. They lived just off the main road of the bustling town.

That evening at Stephen’s house, three old North Shore friends “kindly entertained” Samuel and his wife. One was thirty-nine-year-old Colonel John Hathorne, a wealthy, pious Salem-bred merchant and justice of the peace who had served with Samuel as a magistrate on the General Court for three years. Captain Bartholomew Gedney, another local man in his midforties, was a physician. The third friend, with whom Samuel was closest, was the Reverend Nicholas Noyes, a former schoolmate from Newbury. Noyes was a chubby fellow five years Samuel’s senior. A member of the Harvard class of 1667, he had been a fellow student of the famous blind schoolmaster of Newbury, Thomas Parker, who was his great-uncle. Since 1683 Noyes had been assistant minister of the Salem church. For Samuel, relaxing with old friends, a hearty meal, and invigorating conversation in his dear brother’s house gave him a welcome opportunity to turn from his worries over little Hull.

The graves of his three intimate friends are now clustered in a single cemetery in downtown Salem, the Charter Street Burying Ground, then known as the Burying Point. A sign at the cemetery entrance notes these three men’s “connection with the witchcraft” trials. The Reverend Noyes, who would still be preaching in Salem in 1692, officiated at many hearings that year and openly challenged the

accused witches at their executions. Hathorne and Gedney both served as judges on the witchcraft court, Hathorne proving the most aggressive interrogator. The nineteenth-century historian James Savage deemed Hathorne the “most active magistrate in the prosecution of witches, exceeding mad against them.” Judge Hathorne’s father had come to America in 1630, with John Winthrop. His most famous descendant, Nathaniel Hawthorne, added a w to his surname to dissociate himself from the ancestor whom he felt had “inherited the persecuting spirit, and made himself so conspicuous in the martyrdom of the witches, that their blood may fairly be said to have left a stain upon him.”

After a good night’s sleep in Salem, the Sewalls rose early to prepare for the second leg of their trip. They shared a morning meal with Stephen and Margaret before continuing north in their coach. Stephen had borrowed a spry horse for them, “exceeding fit for our purpose,” to replace their horse, which had been slow the previous day. They got to Newbury “very well in good time.”

Samuel’s parents’ house, which still stands and is occupied today, was in Newbury center just opposite the meetinghouse and north of the Town Green. It was a timber-framed, hall-and-parlor-style house with two large main rooms flanking a central chimney, multiple fireplaces, and additional rooms beneath a lean-to and on the second floor. The basement contained a dairy, where Samuel’s mother churned milk into cream and butter. Henry Sewall, a gentleman farmer, owned thousands of acres in Newbury, which he both purchased and inherited and was gradually passing to his sons and sons-in-law. The first Sewall estate, in the 1630s, consisted of several acres near the old landing place on the Parker River, a few miles south of this house, and five hundred acres inland along the Parker River, which the natives called Quascacunquen.

Newbury began in the 1630s as a tight village around the Lower Green along today’s Route 1A between the Parker River and Old Town Hill. This is where Newbury’s first English settlers, about a hundred immigrants from Wiltshire and Hampshire in southern England, chose house lots and farmed in common. Among these settlers were Samuel’s father and grandfather, who arrived with “a plentiful estate in money, neat cattle [bovines],” and provisions “for a new

plantation.” They sowed the inland soil with English grass seed for grazing. On the extensive salt meadow, now known as wetlands, they harvested salt-marsh hay, a valuable commodity. During the seventeenth century North Shore men cut and dried hundreds of thousands of tons of salt-marsh hay and loaded it onto barges, which they poled through the marsh at high tide to creeks leading to towns, where the hay was moved to ships headed for Boston and the wider market. Salt-marsh hay was used throughout the colonies for bedding and feeding cattle, sheep, and pigs.

The Reverend Parker preached his first American sermon here in 1635, and the settlers started to build a meetinghouse. But they soon realized the far greater value of the land to the north along the wider, deeper Merrimac River. So in 1646 the town center moved a few miles north, to the area of the extant Sewall house. That same year Samuel’s parents—thirty-two-year-old Henry Sewall and Jane Dummer, who was not quite twenty—were married by Judge Richard Saltonstall of the General Court. (Almost a half century later Saltonstall’s son Nathaniel and the Sewalls’ son Samuel would serve together on the witchcraft court.) The newlywed Sewalls returned to England in 1647 with Jane’s parents, who found New England’s climate “not agreeable”—too cold. In 1657, learning that his own eighty-year-old father had died, Henry Sewall Jr. (his father’s only child) returned to Massachusetts to claim his land and estate. While he was there the English monarchy was restored, so in 1661 Henry called for his wife and children to join him.