Sapphire Battersea (16 page)

Read Sapphire Battersea Online

Authors: Jacqueline Wilson

‘I reckon I do like you, Bertie,’ I said, but when he tried to take my hand, I swatted his away. ‘None of that now! No romancing!’

‘Go on, Hetty, just let me put my arm round you – to keep you from falling in.’

‘You’re the one in danger of falling in if you don’t

watch

out,’ I said, giving him a little poke. The sweet smell of his perfume was overpowering in the heat.

‘What’s up? Why are you wrinkling that little nose of yours?’ he asked.

‘I thought it was ladies who were meant to wear the perfume,’ I said.

He wriggled, looking uncomfortable. ‘Sorry. I do stink a bit, I know. I just poured Jarvis’s pomade all over me because I didn’t want to smell of meat, see.’

‘Oh, Bertie.’ I took his hand voluntarily now. ‘You smell fine. Thank you for bringing me here. It’s truly lovely.’

‘I’d like a little house here, right on the island. Wouldn’t it be grand to wake up to the sound of water lapping all around? I’ve often toyed with the idea of throwing in my job with old Jarvis and running off to sea,’ he said dreamily.

‘My father was a sailor,’ I said. ‘Well, so I’ve been told. I’ve never met him. He ran off before I was born.’

‘My pa did likewise. I don’t even know who he was. Could have been Old Nick for all I know or care. Well, lovely as it is, I’d better get you back. We’ll have to hurry to get you home by six or Mrs B will have my guts for garters.’

‘Do you care what she says, then?’

‘Course I don’t – but I want her to let you out

next

Sunday – and the Sunday after that, and all the Sundays following. I’ve taken a fancy to you, Hetty Feather. You’re my girl now.’

I wasn’t sure I should go along with this. Wasn’t I

Jem

’s girl?

‘You know I’m only just fourteen,’ I said.

‘And I’m fifteen, and so we’re just the right ages for each other,’ said Bertie. ‘Don’t worry, Hetty, I promise I won’t lead you astray.’

‘I’d like to see you try!’ I said, jumping back into the boat.

It rocked violently, so that I had to sit down abruptly and cling to the sides.

‘Whoops! You nearly went for a swim after all!’ said Bertie.

He rowed us back to the boathouse and then brought us both a hokey-pokey to eat on our way home. I bit into my iced cream, and shuddered as the cold ran up my teeth and all round my gums.

‘Don’t bite it, girl – lick it!’ said Bertie, showing me how.

I licked and licked and licked.

‘What do you think of it?’ he asked.

‘It’s heavenly!’ I said, grinning all over my face.

An old couple passing by laughed at me. ‘She

looks

as if she’s never tasted iced cream before!’ said the old woman, chuckling.

‘Well, she hasn’t. She’s a poor little orphan girl only just out of the Foundling Hospital,’ said Bertie.

‘Oh, bless her,’ said the old man, fumbling in his waistcoat pocket. ‘Here’s a threepenny, dearie. Treat yourself to another.’

I was shocked speechless, staring at the silver threepenny bit in the palm of my hand.

‘Well, there’s a turn-up!’ said Bertie.

‘I’m

not

an orphan! How many times do I have to tell you?’ I said.

‘Go and give him his threepence back, then,’ said Bertie.

‘No fear! It’s mine,’ I said, popping it into my pocket.

‘Oh well, you can buy the lollipops next week,’ said Bertie.

When we got back to Mr Buchanan’s home, he squeezed my hand. ‘There will be a next week, won’t there, Hetty?’ he said.

‘Yes … please!’

‘I’ll deliver you back, then,’ said Bertie.

Sarah was in her purple bonnet, all ready for her mysterious assignation.

‘You can take off that bonnet and have a spot of supper before you go, or you’ll be coming over

poorly

,’ said Mrs Briskett, consulting her pocket watch. ‘And what time do you call this, then?’ she said, frowning at us.

‘I call it one minute to six, Mrs B,’ said Bertie.

‘I thought I told you half past five?’

‘Or six at the latest, and here we are now – six just about to chime. Punctual to the finest degree!’

‘Hmph!’ said Mrs Briskett, but she invited Bertie to stay for our oyster patty supper.

Sarah only nibbled the edge of hers, and then got up from the table determinedly. ‘I’m sorry, Mrs B, but I’m that het up I can’t eat.’

Mrs Briskett tutted at her, but let her go. ‘Take care now! Don’t get too over-excited, you know it’s not good for you,’ she said.

Bertie and I exchanged glances, while Sarah blushed.

‘Where are you going, Sarah?’ Bertie asked. ‘Are you seeing that fine policeman fellow I’ve seen eyeing you up and down appreciatively?’

Sarah snorted at him. ‘The very idea!’ she said, but she seemed too preoccupied to get properly indignant. She waved goodbye to us, tying up the drawstrings of her bag.

‘Don’t waste all your hard-earned money now,’ said Mrs Briskett.

‘Surely the gentleman is paying for you, Sarah –

or

by definition he ain’t a gentleman,’ said Bertie.

‘You mind your own business, you cocky little urchin,’ said Sarah. ‘I’m off now.’ She looked at Mrs Briskett. ‘Wish me luck, Mrs B!’

‘I’ll do no such thing. You’re a very foolish girl, and I don’t approve,’ said Mrs Briskett – but as Sarah went out of the back door, she called, ‘Good luck, even so!’

‘Come on, Mrs B, out with it! What’s Sarah’s secret? We’re all agog!’ said Bertie.

‘It’s nothing to do with you, lad. My lips are sealed. Now, finish your patty and be off with you.’

‘Such excellent patties too, Mrs B. Hetty’s lucky to be able to learn from you,’ said Bertie.

‘I know you’re just trying to sweet-talk me, Mr Honey-tongue. Go on – scoot!’

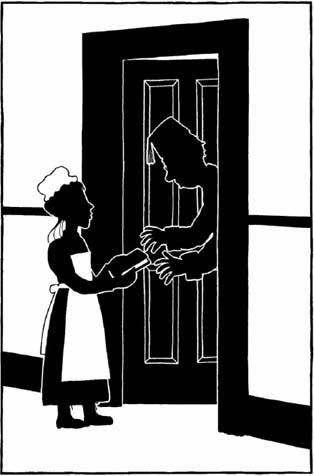

Bertie crammed the last of his patty in his mouth. He stood up, gave Mrs Briskett a little bow – and blew a kiss to me as he went out of the door.

‘I saw that!’ said Mrs Briskett. ‘I’m not sure I should let you near that boy, Hetty. I’ve no idea what he’ll get up to. No, correction: I’ve got plenty of ideas, and none of them good. Come along, help me clear the table. Then you can copy out a few receipts for me, seeing as you’ve got this famously excellent handwriting.’

I meekly did as I was told. Mrs Briskett was all of a fidget, fussing around the kitchen, starting to

turn

out her larder but losing heart halfway through. She kept sighing. I wondered if she were wishing she had a Sunday outing too.

‘Did Mr Briskett pass away a long time ago, Mrs Briskett?’ I asked.

‘What? There was never any such person! I told you, it’s a courtesy title.’

‘Did you ever have a sweetheart, Mrs B?’

‘Mrs

Briskett

! No, I’ve never had no time for men,’ she said. ‘You can’t trust them. You’re a case in point. It’s clear some bad lad led your poor mother astray.’

‘Mrs Briskett,

is

that man in the grocer’s shop Sarah’s sweetheart?’

Mrs Briskett rolled her eyes. ‘Of course not, Hetty. That gentleman happens to be respectably married.’

‘Then why is she seeing him? Where do they go?’

Mrs Briskett tapped my nose with her finger. ‘Ask no questions and you’ll be told no lies,’ she said.

‘The matrons always used to say that to me at the hospital,’ I said.

‘I’m not surprised. You’re a terrible girl for questions, Hetty Feather.’

‘How else am I to find out about things?’ I said.

‘There aren’t many answers worth knowing,’ said Mrs Briskett, sorting jars of sour pickles. Her

mouth

was puckered, as if she were actually sucking them. I wondered what it would be like to be Mrs Briskett, with no family at all, cooking tempting and tasty dishes for one pernickety old gentleman who rarely cleared his plate.

‘Do you

like

working here, Mrs Briskett?’

‘Questions, questions! You can’t seem to help it! Yes, of course I do. You can’t go much higher than this – cook-housekeeper in a lovely villa. I started off as a kitchen maid when I first went into service, but the cook was a regular harridan and scared the life out of me. Then I worked for a young couple, but the missus was too flighty and didn’t give me no direction. Then I worked in another home where the missus was the exact opposite, telling me what to do all day long. I used to hear her voice nag-nag-nagging even in my dreams. And

then

I came to work for the master here, and what a joy it is to have no missus whatsoever.’

‘But, Mrs Briskett, wouldn’t you like to

be

a missus one day?’

Mrs Briskett stared at me as if I’d suggested she become an Indian Princess or an opera singer. ‘Of course not, Hetty. I hope you’re not going to turn out to be one of those girls with ideas above their station.’

I went to bed that night, determined to keep all my ideas above my station. I wrote a long letter to

Mama

, telling her that I’d been to church and had a jolly boat trip with a new chum. I did not specify exactly who this new chum was. I wrote to Jem too, and I described the boat trip – but I thought it best not to mention any chum at all.

I GOT INTO

the habit of copying Mr Buchanan’s writing every day. At first it was hard work deciphering all his curlicues and squiggles, but after a few days I grew used to his style and could copy quickly and easily. I could not say his work

read

quickly and easily. He used such long convoluted sentences that you lost all sense of what he was saying. He spent page after page laboriously describing every little detail. His characters rarely talked to each other, and when they did, it was with the stiff erudition of elderly clergymen, even though they were children. They were quite the most tedious children too, forever quoting the Bible to each other and pointing out morals.

I had read Miss Smith’s stories with huge enjoyment, but Mr Buchanan’s tales were so turgid that I yawned as I copied them.

‘Did you not get enough sleep, Hetty? That was a fearsome yawn!’ said Mr Buchanan sharply.

‘I’m sorry, sir. I – I’m just a little tired today,’ I said, pressing my lips together.

‘You’re making good progress with your copying. You will have the manuscript ready for the publisher by the end of the month. Now, I have to cast my mind about and find a subject for a new story …’ He paused. I realized he was expecting me to show some interest in this project.

‘You’re very industrious, sir,’ I said dutifully.

‘I have to work hard because, alas, my stories do not sell particularly well,’ he said.

‘Oh goodness, sir, I wonder why,’ I said – though I knew very well!

‘I think they are written in too fine a literary style,’ said Mr Buchanan. ‘And my characters are well-brought-up young ladies and gentlemen. Perhaps I should copy your friend Miss Smith and write about street waifs.

Her

stories are immensely popular.’

‘Miss Smith goes out into the London streets, sir, and interviews the children there,’ I said.

‘I dare say. And very admirable too. But you are surely not suggesting I do likewise?’

I tried to picture Mr Buchanan picking his way fastidiously across muddy pavements, summoning street children imperiously. They’d simply jeer at him. They might even throw stones.