Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion (6 page)

Furthermore, there is the inconsistency of the date when Brown began working at Lockheed Vega.

Schatzkin places his arrival at the end of October 1942, while Moore states the arrival date was more than one and a half years later, in June 1944—a start date that is also corroborated by the account given in the

Who’s Who

biography.

So which version is correct, the revised timeline based on Navy records or the preexisting biographic timeline that was developed with Brown’s full knowledge?

Unfortunately, Brown is no longer around to comment, having passed away in 1985.

To support his argument for Brown’s early departure, Schatzkin cites a Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) report that claims to have been filed in March 1943.

This report states that by that date, Brown had resigned from the Navy and returned to his home in Los Angeles, as told by an anonymous informant (name blacked out).

But should this anonymous informant be relied upon?

Schatzkin himself admits that much of the information the report provides about Brown is inaccurate and contradictory.

The filing date given on the report appears to be among the fabrications.

The report states, “He [Brown] had his own laboratory and had purchased equipment from his own funds for use in his experimental work, and this equipment was taken by Subject when he was detached from the Fleet Service School.”

This equipment included gravito-electric sensor equipment, which was among the apparatus that had earlier been transported from Brown’s University of Pennsylvania laboratory to Norfolk.

According to Schatzkin’s revised timeline, this equipment would have then been transported from Norfolk to Los Angeles around October 1942, when he claims that Brown was discharged.

However, the revised timeline does not jibe well with Brown’s account of the dates and locations at which he was conducting gravito-electric measurements.

In his March 1975 paper titled “Anomalous Diurnal and Secular Variations in the Self-Potential of Certain Rocks,” Brown discusses dates and locations at which he conducted gravito-electric measurements, mentioning his work at the Naval Research Laboratory (1931–1933) and his research at the University of Pennsylvania (1939).

Then he writes, “The investigation was interrupted by World War II but was resumed in 1944 in California by the Townsend Brown Foundation (an Ohio non-profit corporation) and was carried forward in two locations in especially constructed shielded rooms at constant temperature.”

39

If we accept the traditional timeline in which Brown is discharged from the Navy in December 1943 and transports his equipment to California around that same time, then his stated 1944 date for resuming his gravito-electric measurements in California makes sense.

This implies that he wasted no time in setting up his equipment to start collecting data once again.

On the other hand, if we accept the Navy-FBI timeline that has Brown being discharged in October 1942, we would have to conclude that he shipped his equipment to California at the end of 1942 and left it sitting boxed up for more than a year before setting it up.

However, it seems unlikely that Brown would have tolerated having his detectors “off the air” for such a long time period.

Could it be that the FBI report was actually filed in 1944 and its date was at some later point changed to 1943 in an effort to rewrite Brown’s official history?

To support his 1942 date for Brown’s Navy discharge, Schatzkin refers to a bound laboratory notebook that he believes Brown had used while at Lockheed Vega.

40

The ledger’s notes are written in Brown’s handwriting and contain occasional dates that also appear in Brown’s handwriting, the oldest date near the beginning of the book being December 1, 1942, and the most recent date near the end of the book being May 2, 1944.

The notebook’s cover page is neatly hand printed and reads:

*1

T.

T.

B

ROWN

V

EGA

A

IRCRAFT

C

ORP

.

B

URBANK

, C

ALIF

.

NOTES

We are left to consider the possibility that the notebook contains lecture notes that Brown began writing while teaching at the Atlantic Fleet schools in Norfolk.

The last dated entry in the notebook would have been made after Brown had left the Navy and had moved to California, prior to going to work at Lockheed.

He may have labeled the notebook as “Vega Aircraft Corp.”

because he wanted his notes with him at his new job, or he may have purposely mislabeled the notebook in this way so that naval intelligence would not squirrel it away in some classified storage room.

If we instead accept that Brown actually wrote these notes while he was at Lockheed Vega and that he began working there as early as October 1942, then we are confronted with the inconsistency of this date with those given in Brown’s autobiographies and with the question of why his gravito-electric sensor equipment would supposedly have been stored unused for more than a year.

Also, with this early-departure scenario, it is difficult to understand why Brown wished to resign from the Navy at the height of World War II, just nine months after Japan had bombed Pearl Harbor and at a time when his Navy career looked so promising.

According to the FBI report, Brown was “reported to know more about Radar detection than any individual in the U.S.

Navy.”

So why would the Navy let him go at such a crucial time of need?

If, on the other hand, Brown’s decision to leave the Navy arose as a result of a nervous breakdown brought about by the great weight of guilt he felt from being associated with a project that had suffered an immensely tragic outcome, as Moore and Vassilatos suggest, then his departure at the later date of December 1943 becomes more understandable.

The Navy administrators who had knowledge of this classified project and who themselves shared the guilt of its outcome would have sympathized with Brown’s wish for departure and released him from service, even knowing how indispensable he was.

According to Schatzkin, “Starting in the fall of 1942 there is virtually no documentation available that might shed some light on just what Brown was doing during those crucial years.”

41

He notes that the Brown family files are devoid of any correspondence or documentation from roughly that time until the end of World War II and that they have very little information about his activities at Lockheed Vega.

So considering the absence of information from both the Navy records and the Brown family files, we are left only to speculate.

Had some military intelligence organization gone out of its way to ensure that any record of Brown’s activities during this period was either erased or classified to keep a tight cover on Brown’s wartime research activities?

Despite its official denial, did the Navy conduct a highly secret project on ship invisibility and was Brown involved in it?

Perhaps the adage “Where there’s smoke, there’s fire” applies here.

One suspects that something very strange and clandestine was under way in the Philadelphia–D.C.–Norfolk area during the 1942 to 1943 time period.

In July 1946, the

Eldridge

was decommissioned and placed in the Reserve Fleet.

In 1951, the United States transferred her to the Greek navy, in which she served as the HS

Leon

until the 1990s.

One Greek engineering professor related that he formerly served on the

Leon

as a naval officer specializing in electrical engineering.

42

While on board, he noted several odd things about the ship.

One was that he saw numerous remnants on the inside of its hull of heavy-duty cables that once ran along the length of the ship.

These were in the form of insulated metal bars measuring 10 to 15 centimeters in width that had been cut in between their points of attachment to the hull.

Other large-diameter cables were also present fully intact that were presumably part of the electric wiring for the ship’s propulsion system.

The

Eldridge

was a Cannon class electric drive ship, meaning that instead of having a shaft running from its engine directly to its propeller, as most ships do, it had a diesel-powered electrical generator whose power was conveyed through heavy-duty cables to a huge electric motor at the ship’s stern that drove the propeller.

The

Eldridge’

s ability to produce large amounts of electric power with an onboard generator would have made it ideal to use in conducting the Philadelphia Experiment.

The other unusual thing that the professor noted was that one room adjacent to the ship’s hull was barred from access, its hatch having been welded shut.

The commanding officer had instructed the ship’s crew that it was forbidden for anyone to try to enter the sealed room.

What this forbidden zone hid will perhaps never be known, for the ship was decommissioned and sold as scrap sometime after 1992.

2

BEYOND ROCKET PROPULSION

2.1 • BROWN’S ELECTRIFIED FLYING DISCS

During the years following World War II, Brown continued to improve his gravitator device in his spare time, financing his efforts through the Townsend Brown Foundation.

By 1950 he had built a test apparatus to demonstrate the electrogravitic propulsion concept in a pair of disc airfoils.

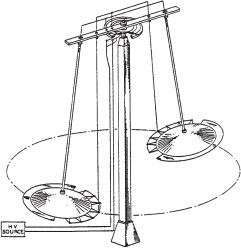

He set a 6-foot-long horizontal beam on a pivot so that it could rotate about its midpoint, and from each end of the beam he suspended two lightweight saucer discs by means of 7-foot-long tethers (figure 2.1).

When the saucers were in flight, rotating tethers extended sideways and expanded the diameter of the flight course to as much as 20 feet.

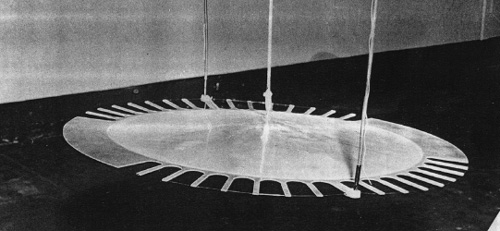

In one version, each disc was made of two curved aluminum shells, measuring 1.5 feet in diameter, fixed on either side of a 2-foot

-

diameter Plexiglas sheet (figure 2.2).

1

High-voltage power of up to 50,000 volts was supplied through feed wires to positively charge a fine outboard wire running along each disc’s leading edge and to negatively charge the aluminum disc body.

When electrified with approximately 50 watts of this high-tension power, the discs traveled around their 20-foot-diameter course at speeds of up to twelve miles per hour.

2,

3

Figure 2.1.

Thomas Townsend

Brown’s flying disc setup.

Figure 2.2.

Thomas Townsend Brown’s 2-foot-diameter experimental disc

airfoil.

(From Project Winterhaven, plate 1; photo courtesy of the Townsend

Brown Family and Qualight, L.L.C.)

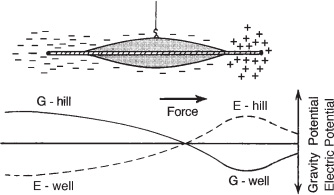

The wire electrodes ionized the surrounding air, forming a cloud of positive ions around the leading wire and a cloud of negative ions around the disc body.

Although ions would continuously leave these clouds as a result of being attracted to the oppositely charged electrodes, the electrodes would resupply ions at a sufficiently fast rate so as to maintain a positive-ion space charge at the front of the disc and a negative-ion space charge on the disc body (see figure 2.3).

As to how the disc generates its propulsive force, two possibilities present themselves.

One is that the ion clouds it emits produce electrostatic fields that act on charges attached to the disc’s leading-edge wire and to its main body, producing a net forward thrust.

The other possibility is that an electrogravitic thrust may be present whereby the positive- and negative-ion clouds would create, respectively, a gravity potential well and a gravity potential hill in their vicinity.

As new positive charges are continuously added to the cloud, they replace charges that leave the cloud through attraction to the disc’s negative pole.

As a result, the cloud will maintain a moderately deep gravity well at its bow through a kind of dynamic equilibrium.

The same will hold for the disc’s rearward negative charges.

Despite the mobility of the individual negative ions, the negative-ion cloud as a whole will persist and create a net gravity hill.

Consequently, the gravity potential gradient established across the disc’s body between this hill and the well propells the disc forward in the direction of its positive-ion cloud.

Figure 2.3.

A side view of one of Thomas Townsend Brown’s flying discs, as normally energized, showing the location of its ion-space charges and induced gravity field gradient.

(P.

LaViolette, © 1994)

By accumulating charges in the air in the form of fore and aft ion clouds, large quantities of charge may build up, comparable to the quantity of charge on the plates of a high-K dielectric capacitor.

But because these charges are freshly created, there is little time for them to polarize the ambient air.

Furthermore, due to the disc’s forward motion, the air dielectric around the disc is continuously replaced by new, unpolarized air, and this also contributes to maintaining the air dielectric in a relatively unpolarized state.

Consequently, the electric and gravity potential fields are able to extend between the oppositely charged fore and aft clouds unopposed by any electric dipole moment in the intervening air.

Hence a substantial gravity field gradient could span the disc and exert a maximal forward thrust.

As the disc moves forward, its associated positive- and negative-ion clouds also move forward, transporting their generated electrostatic and gravity field gradients along with them.

Consequently, each disc rides its advancing wave much like a surfer riding an ocean wave.

Dr.

Mason Rose, one of Townsend’s colleagues, describes the disc’s gravitic principle of operation:

The saucers made by Brown have no propellers, no jets, no moving parts at all.

They create a modification of the gravitational field around themselves, which is analogous to putting them on the incline of a hill.

They act like a surfboard on a wave.

.

.

.

The electro-gravitational saucer creates its own “hill,” which is a local distortion of the gravitational field, then it takes this “hill” with it in any chosen direction and at any rate.

4

A full-scale version of Brown’s vehicle was thought to be able to accelerate to thousands of miles per hour, change direction, or stop merely by altering the intensity, polarity, and direction of its electric charge.

Because the wavelike distortion of the local gravitational field would pull with an equal force on all particles of matter, the ship, its occupants, and its load would all respond equally to these maneuvers.

The occupants would feel no stress at all, no matter how sharp the turn or how great the acceleration.

A turbo-jet airplane, by comparison, must produce a twentyfold increase in thrust just to attain a twofold gain in speed.

Whereas jets and rockets attempt to combat the force of gravity through the application of opposed brute force, electrogravitics instead attempts to directly control gravity so that this longtime adversary is made to work for the craft rather than against it.

Partly with the help of his friend Kitselman, who was then teaching calculus in Pearl Harbor, Brown’s discs came to the attention of Admiral Arthur Radford, commander in chief of the U.S.

Pacific Fleet at the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard.

In 1950, Brown was hired as a consulting physicist to stage a demonstration.

Nothing immediately came of this.

However, two years later, on March 21, 1952, Brown was visited at his Los Angeles laboratory by Vic Bertrandias, a well-connected Air Force major general.

He dropped in unexpectedly, just when Brown was about to demonstrate his flying discs to a group of colleagues.

Once there, Bertrandias demanded that he be included in the demonstration.

Having formerly served as vice president of Douglas Aircraft, he was well informed on the state of the art in aviation technology and knew that Brown’s discs could have important military applications.

Shaken by what he saw, Bertrandias urgently telephoned Lieutenant General H.

A.

Craig the following morning to voice his concerns.

An excerpt from a declassified transcript of their conversation reads as follows:

Bertrandias: the thing frightened me—for the fact that it is being held or conducted by a private group.

I was in there from about 1:30 until 5:00 in the afternoon and I saw these two models that fly and the thing has such a terrific impact that I thought we ought to find out something about it—who the people are and whether the thing is legitimate .

.

.

if it ever gets away, I say it is in the stage in which the atomic development was in the early days.

Craig: I see.

Bertrandias: It was quite frightening.

I made the inquiry whether the Air Force or the Navy knew anything about it and I was told—no.

But I tell you, after hearing it and all the other things that I had heard, I was quite concerned about it.

.

.

.

I am of the opinion that if all I heard the other day—if it ever comes true, and somebody occupies space with that instrument, it is a bad deal for somebody.

Craig: Well, we will look into it, Vic.

Craig subsequently initiated a background check on the Townsend Brown Foundation.

Bertrandias was also a close friend of General Albert Boyd, director of Air Force Systems Command at Wright Air Development Center.

It was under Boyd that Air Force Systems Command carried out most of its early, super-secret research projects on antigravity propulsion.

5

Brown’s work may have been encroaching into an area in which the Air Force had established a substantial lead.

Perhaps Brown sensed Bertrandias’s fearful reaction and was concerned that he might initiate formal military classification of Brown’s electrogravitic work, for just two weeks after Bertrandias’s visit, Brown and his two associates, Mason Rose and Bradford Shank, held a press conference to publicize the fantastic possibilities of this electrogravitic propulsion technology.

In this way, they got the word out before things got too hushed up.

Reporters from the

Los Angeles

Times were invited to view Brown’s flying discs in operation and had a chance to read a paper prepared by Rose that explained the Biefeld-Brown antigravity effect and how it could be used to propel a full-scale antigravity spacecraft.

The next day the

Times

carried a story about Brown’s discs and how flying saucers (also popularly known as UFOs, short for “unidentified or unconventional flying objects”) might function on a similar principle.

6

It quoted Rose as saying that details about Brown’s work had been given to some Navy admirals and that there was military interest, although no censorship had yet been imposed.

Like the Air Force, the Navy had an active interest in advanced aviation technology.

About two months after the L.A.

press conference, in June 1952, the Office of Naval Research (ONR) sent Will Cady to investigate a number of Brown’s inventions, including his flying discs.

The ONR data indicate that Cady witnessed a pair of 1.5-foot-diameter discs achieve a top speed of three miles per hour with a propulsion efficiency of 1.5 percent while drawing 15 watts of power at 47 kilovolts.

7

This was about one-fourth the speed and efficiency obtained with the 2-foot-diameter model.

Did Brown stage this more modest performance with the intention to reveal just enough to get the military interested but not enough to make the demonstration so astounding that they might demand classification of his work?

One alternative suggested by Paul Schatzkin is that there had been a security breach during Brown’s Pearl Harbor demonstration and that Brown had been asked to purposely downplay the performance of his device in order to mislead foreign intelligence agents into thinking that his invention was not worth pursuing.

8