Sergeant Gander (4 page)

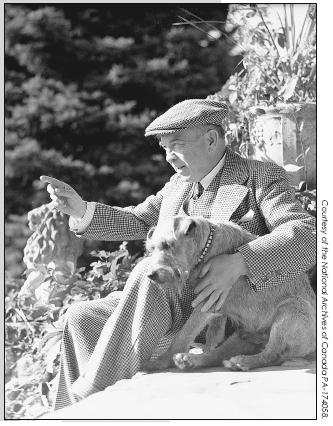

Mackenzie King

William Lyon Mackenzie King was Canada's longest-serving prime minister. The

grandson of William Lyon Mackenzie, leader of the Rebellion of 1837, King was

selected by the Liberal Party as the successor to Sir Wilfred Laurier in 1920, and was

elected prime minister in 1921. King had many years of experience in politics before

being elected prime minister, including serving as the minister of labour under the

Laurier government. He was a political science and law graduate from the University

of Toronto, and also held degrees from the universities of Harvard and Chicago.

When the Second World War began in Europe, the Canadian government did

not automatically commit itself to go to war on behalf of Great Britain. King was

adamant that only the Canadian Parliament could decide upon a declaration of

war. However, he felt that Canada did have an obligation to support Great Britain

and following a special session of Parliament, held on September 7, 1939, King

announced that “if this house will not support us in that policy, it will have to find

some other government to assume the responsibilities of the present.”

12

On September

10, 1939, after several days of debate in the House of Commons, Canada issued a

formal declaration of war against Germany.

The Rt. Hon.W.L. Mackenâzie King with his dog Pat at Moorside Cotâtage, August 21, 1940.

King was a staunch supporter of supplying

aid to Great Britain throughout the war. He also

provided a vital communications link between

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and

American President Franklin Roosevelt, until

the Americans formally entered the war in

1941. Throughout the war, King's government

ensured the steady flow of war materials to

Great Britain.

Mackenzie King was re-elected in 1945,

just after the end of the war in Europe. He

announced his retirement in 1948, having served

twenty-two years as prime minister. He died of

pneumonia on July 22, 1950, and is buried in

Toronto at Mount Pleasant Cemetery.

Mackenzie King was also a dog lover. In

July 1924, King was given an Irish Terrier

puppy by some close friends. He named the dog

Pat and the two became devoted companions.

Daily walks and evenings sharing cookies and

Ovaltine became part of the pair's regular

routine. Pat was so important to King that the little dog was mentioned in almost

every entry in his personal diary over the next seventeen years.

In due time, Pat became sick and died in July 1941, an event that caused King

much sorrow. In his December 31, 1941, diary entry, King wrote, “As I think it all

over tonight, the event that touched me most deeply of all was perhaps the death of little

Pat. Our years together, and particularly our months in the early spring and summer,

have been a true spiritual pilgrimage. That little dog has taught me how to live, and

how to look forward, without concern, to the arms that will be around me when I too,

pass away. We shall be together in the Beyond. Of that I am perfectly sure.”

12

Ferry Command

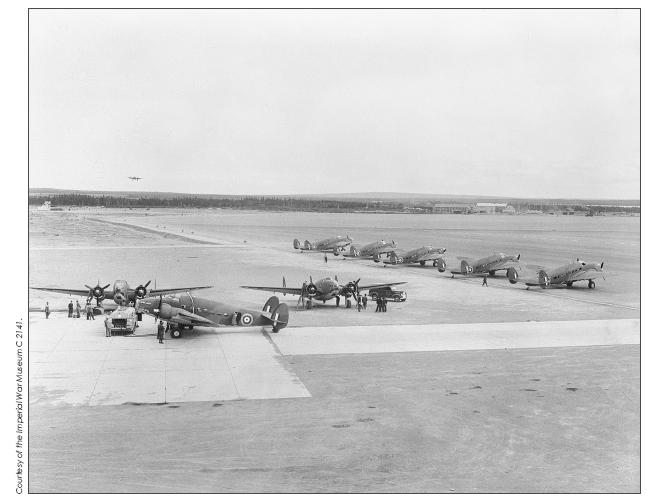

Ferry Command was created in response to the desperate need for airplanes to support the

British war effort. British airplane factories were obvious targets for German bombers.

In an effort to ensure a continuous supply of aircraft with which to defend itself, Britain

looked to Canada and the United States to keep the Royal Air Force supplied. Recognizing

that surface shipping over the Atlantic Ocean was very slow and very vulnerable to

attack, the idea of having pilots “ferry” the planes across the ocean was developed.

However, the plan found little support among RAF commanders, who felt that

the distance across the Atlantic was too far, and the weather too unpredictable for the

idea to be worthwhile in practice. Moreover, the RAF couldn't spare any pilots to ferry

the aircraft. Lord Beaverbrook, senior cabinet minister in Britain's government,

ignored the RAF's concerns and set up an all-civilian organization to implement

the operation. The ferrying program experienced success throughout the 1940s and

early 1941, and by July 1941 it was taken over by the Royal Air Force. At that point,

Air Chief Marshall Sir Frederick Bowhill was placed in charge of Ferry Command,

and its primary function was to fly newly constructed aircraft from Canadian and

American factories to operational units in Great Britain.

Its pilots were a mixed lot â crop dusters, barnstormers, bush pilots, and stunt pilots;

Americans, Canadians, and a variety of Europeans. Few of the pilots had any trans-

Atlantic experience, but all of them shared the courage to give it a try. The civilian

ranks were often supplemented by recent graduates from the British Commonwealth

Air Training Plan,

14

made up of pilots, navigators, wireless operators who wanted

to gain some transatlantic flight experience, and experienced Royal Canadian Air

Force pilots who were en route to assignments overseas. Gander Airport was used as the

refuelling stop on the first ferry route. The success of the program meant that further

routes were added. Smaller range planes could refuel in Goose Bay (Labrador),

Greenland, and Iceland. There was also a South Route that linked the United States

to Egypt. In March 1943, Ferry Command was subsumed into Transport Command,

which had a global, as opposed to merely trans-Atlantic, operational area. Throughout

the course of the war over 9,000 aircraft were ferried across the Atlantic.

Royal Air Force Ferry Command, October 1941. Lockheed Hudson Mark IIIs are prepared for their trans-Atlantic ferry flights.

2: Sergeant Gander, Royal Rifles of Canada

Mobilized at Quebec City, in July 1940, the Royal Rifles of Canada drew most of their recruits from eastern Quebec and western New Brunswick. It was an English-speaking unit, but almost one quarter of the recruits were bilingual French Canadians. In the fall of 1940, the Royal Rifles were transferred to Sussex, New Brunswick, for further training, and by November they had been moved to Newfoundland. Their primary task there was to protect Gander Airport from German attack. They had been performing guard duty, combined with some training, for about six months when they acquired their regimental mascot, Sergeant Gander. As George MacDonell remembers, “â¦the regiment was presented with a purebred Newfoundland dog. He was jet black and looked more like a small pony than a dog. He was named Gander, after the airport. Gander was the biggest dog I had ever seen. He had a heavy, furry coat and webs between his toes, and could swim in the cold Atlantic like a walrus.”

The Royal Rifles adored their new recruit. A handler, Fred Kelly, was assigned to Gander. Each day Kelly fed him, brushed him, and gave him a shower. Although Gander loved his daily shower, Kelly needed to be quick on his feet, because once Gander was finished, one big shake of his body was all that was needed to leave his handler soaking wet. Another one of Gander's tricks was to bolt outside after his shower and roll in the sand, leaving himself a filthy mess. Therefore, every effort was made to keep Gander inside until his coat had dried. Fred Kelly recalls, “Gander was no problem to look after. I had dogs all my life and we kind of took to each other right away. He ate anything and everything but had a particular taste for beer which he would drink out of the sink. He was a very playful dog and would often stop me in my tracks by resting his front paws on my shoulders.”

2

The Royal Rifles treated Gander like one of their own. Gander was given his own kitbag, just like the other soldiers, a kitbag that contained his blanket, brush, and food bowl. The soldiers even built Gander a doghouse, but he didn't like it very much. He howled and cried so much that Fred Kelly simply brought him inside the barracks and let him sleep on the floor beside his bed.

Gander appeared to be well aware of his importance in the regiment. Explains George MacDonell, “He was soon promoted to sergeant and wore his red stripes on a black leather harness with the regimental badge. He proudly strutted at the head of the band on church parades and ⦠refused all other canines entry to the barracks.”

3

In May 1941, the Royal Rifles were transferred to St. John's, Newfoundland, to perform garrison duty and receive further training. By September 1941, the Royal Rifles had been moved back to Canada, and were stationed at Saint John, New Brunswick. At that point, the director of military training, Colonel John Lawson, identified the Royal Rifles as “insufficiently trained and not recommended for operations.”

4

Despite his observation, a month later the Royal Rifles received their orders to prepare for overseas duty. Although their destination was unknown, the decision had been made that the Royal Rifles, along with the Winnipeg Grenadiers, would be sent to Hong Kong to help reinforce the British garrison against Japanese attack. The British had been hoping that the combination of Japan's military commitments in China, their fear of antagonizing the United States, and the threat of an attack by Soviet Russia on their northern borders, might deter Japan from attacking Britain's Asian colonies. However, when Japan signed a Neutrality Pact with the Soviet Union in April 1941, the British recognized the increased threat to their holdings in Asia. With Great Britain tied down defending their homeland from German attack, they needed all the help they could get to protect their colonies in other parts of the world.

The decision to reinforce the defences of Hong Kong was a contentious one. Both the British chiefs of staff and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill opposed any further strengthening of the colony. In August 1940, the chiefs of staff stated:

Hong Kong is not a vital interest and the garrison could not

withstand Japanese attack ⦠Even if we had a strong fleet in the

Far East, it is doubtful that Hong Kong could be held now that

the Japanese are firmly established on the mainland of China â¦

In the event of war, Hong Kong must be regarded as an outpost

and held as long as possible. We should resist the inevitably strong

pressure to reinforce Hong Kong and we should certainly be

unable to relieve it.

5

This sentiment was echoed by Churchill at the beginning of 1941, when he stated, “If Japan goes to war with us there is not the slightest chance of holding Hong Kong or relieving it. It is most unwise to increase the loss we shall suffer there. Instead of increasing the garrison it ought to be reduced to a symbolic scale ⦠We must avoid frittering away our resources on untenable positions. Japan will think long before declaring war on the British Empire and whether there are two or six battalions at Hong Kong will make no difference to her choice. I wish we had fewer troops there, but to move any of them would be noticeable and dangerous.”

6

Yet there was a faction, including Air Chief Marshall Sir Robert Brooke-Popham, Rear Admiral Sir Tom Phillips, and Major-General A.E. Grasett (commander of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Force), who believed that Hong Kong should be held. Grasett's appeal to the British War Office, suggesting that the Canadians might be willing to assist in the reinforcement of Hong Kong, found some receptive ears and in September 1941, a cable was sent to Ottawa, proposing that,

A small re-enforcement of the garrison of Hong Kong, e.g. by one

or two battalions, would be very fully justified. It would increase

the strength of the garrison out of all proportion to the actual

numbers involved and it would provide a very strong stimulus to

the garrison and to the Colony, it would further have a great moral

effect in the whole of the Far East and would reassure Chiang

Kai Shek as to the reality of our intent to hold the Island ⦠We

should therefore be most grateful if the Canadian Government

would consider whether one or two Canadian battalions could be

provided from Canada for this purposeâ¦.

7