Sexology of the Vaginal Orgasm (3 page)

Read Sexology of the Vaginal Orgasm Online

Authors: Karl F. Stifter

There are a few basic requirements for this free play and the imaginative use of all registers of pleasure. It is in reality much like playing an organ. Organ and organism have the same linguistic root (gr.

organon = tool

). It is not just a coincidence that the German word “orgeln” (playing the organ) was once used as a vulgar expression for coitus. Today this word is still used by hunters to describe the sounds pro- duced by a stag while rutting. Just as dexterity alone is not enough to be a good organist, it is also not enough for the sought-after player of love. For both, virtuosity consists in

an almost trance-like merging of sexual sensations, accom- panied by the gentle stroke of finger tips. With growing intensity the salvation of the finale happens by itself. Orga- nist and lovers are both passionately in love with their play. It is an exception when they approach their goal head- on. Rather, they lose their way in imaginative fugues, by making variants of diverse lips, tongues and membranes vibrate.

Real virtuousi don’t need notes to play. They can dispense with them and can also afford to stop thinking in the free play. This way both are able to rise up like on a cloud of sounds and be carried away. One allows oneself an end, which does not have to have a certain outcome, and thus allows for anything to happen.

One of the most common causes of anorgasmia is the obses- sive, stubborn concentration on sexual sensations which are assumed to immediately precede orgasm. Such and similar forms of sceptical self-observation have a fateful conse- quence in the dual sense of the word. First, attention chan- nelled in this direction leads to a disillusioning flattening of pleasure and second, orgasm is a reflex which like all other reflexes subject to voluntary control is inhibited by much more intensive attention. However, one must also bear in mind that reflexes show a range of variations in terms of inhibition. This means that in some persons a reflex muscu- lar twitching can be triggered off by a light tap of the knee, while others only react following a strong smack on the patellar tendon below the knee cap. Both are perfectly normal, i.e., the neuronal apparatus conveying the reflex is intact. Just as there is a normal range of the patellar reflex threshold, there is also such in triggering an orgasm. The reflex thresholds are generally influenced by other factors

as well, such as psychological inhibitions, drugs and emo- tional states.

1.5. Reasons for the Female Orgasm

It is said that nature does nothing futilely. While we are more than happy that mother nature has given us the orgasm as a gift of pleasure, it is still a mystery why she has done so. We don’t really need it to ensure the survival of the species. And we all know that we can easily become pregnant with- out it. So why does it exist at all?

One of the most traditional answers of behavioral research is its function in partner bonds. The experience of orgasmic pleasure creates a psychological bond between the partners. (Eibl-Eibesfeldt, 184). There is certainly something true about this hypothesis, but this answer is not entirely con- vincing. If its sole function were to strengthen the couple’s bond then such a great variation in the likelihood of an orgasm should not be expected. Instead, each coitus should culminate in a temporally well coordinated orgasm that is as psychologically gratifying as possible. Unfortunately, this is not always the case.

More recent studies see the female orgasm as an evolutio- nary mechanism for women to influence the likelihood of their pregnancy. The orgasmic contractions of the uterus and the related dipping of the neck of the uterus in the “puddle of ejaculate” functions as a sort of “suction cap” which facilitates insemination. According to this hypothe- sis the likelihood of female orgasm must not just depend on the male’s quality as a lover but also on his bringing “biological quality” in the sense of “good genes” so as to en-

sure the greatest possible success in procreation. A sign of “biological quality” which is apparently assessed by all women according to the same standards is attractiveness. Studies have shown that the more attractive men are seen by women the more frequently they engage in extramarital relationships and the shorter the period of courting preced- ing the first intercourse. So far so good, but this does not really require any sophisticated studies. This is part of everyday experience. A “hotter” insight in connection with our subject matter is that male attractiveness influences the likelihood of a partner experiencing an orgasm when making love. (Thornbill et al., 1995)

This finding, which was confirmed by a survey conducted with 388 American and German women, created a big stir. (Shakelford, 2000) This explanatory model has certainly some validity. Yet in my view it is overestimated in terms of the conception-promoting effect of orgasmic movements of the uterus. As an argument, I’d like to refer to the research findings of Devendra Singh (et al., 1998), for example, that show that even a strong desire to have children does not have any effect on promoting orgasm. If there is any socio-biological explanation for sexual climax, then I believe it to be a sophisticated “pleasure premium” to stimulate women to continue having sex with an attractive man, so as to ensure genetic benefits for their offspring. (Stifter, 1993) In connection with a holistic and reciprocal erotiza- tion, attractiveness plays such a significant, multi-faceted role, thus meriting a detailed analysis in a separate chapter. Related detailed knowledge is indispensable since biologi- cal influences on our behavior are met with a lot of resis- tance in terms of world view. There is profound suspicion when it comes to using innate behavior as an excuse for role clichés. By way of illustration and elucidation I would like

to cite the science journalist Nuber: “If the ability of a woman to reach orgasm is not just dependent on the man’s sexual intuitive power but also on the quality of his genet- ic makeup, then he doesn’t have to worry about it when she cannot come. And if female orgasm has nothing to do with love, then he doesn’t have to have any doubts about her feelings when she doesn’t experience one.” (Nuber, 1996; p. 28)

2.

The Basic Features of Erotic Attraction

Darwin (1874) was impressed by the various notions and preferences held by different cultures for beauty: “

It is certainly not true that there is in the mind of man any universal standard of beauty with respect to the human body

” (cited in: Grammer, 1974)

If Darwin is right, and there are no general criteria for asses- sing beauty, then beauty lies wholly in the eyes of the behol- der. Aesthetics would then be a matter of individual taste. One of the few cultural-comparative studies contradicts this hypothesis. Morse (et al. 1978) conducted assessments of attractiveness in the U.S.A. and in South Africa. Both of the cultural circles studied showed a high degree of concor- dance in assessing the attractiveness of people. Apparent- ly, within a given culture men and women used the same standards to describe physical attractiveness (Grammer, 1994; p. 151).

One of the first studies on this subject carried out by Iliffe (1960) speaks in favour of assuming a general notion of beau- ty. Under the motto “Who is the most beautiful in all the land?” he had the readers of an English journal assess twelve pictures of young women. He obtained 4,355 answers and concluded that one and the same portrait of a woman was deemed the most beautiful in different parts of the country and by individuals from different professional groups. There is thus a general understanding of beauty, at least with regard to faces. The existence of such a general notion of beauty has been confirmed by Henss (1987 and 1988) (Grammer, 1994; p. 150). Beauty is universal and interna-

tional. It makes an impression regardless of race, ethnic group or skin color.

As soon as physical attractiveness plays a role in a couple finding each other, the laws of the “free marriage market” come to bear. One’s own value on this market depends not only on self-assessment but also on the assessment of others. It is only possible to be assessed by others when there is a standard of attractiveness shared by others within a popu- lation. The high concordance found by men when it comes to assessing women can be explained by the fact that men obviously use these general criteria of selection for orienta- tion. This, of course, automatically results in a competition for women considered desirable.

Henss (1991) has divided the assessment of attractiveness in three criteria. He ascertained that men and women use the same standards in assessing beauty, sexual attraction and sympathy. Those who were seen as being attractive are also those who are regarded as beautiful and sexually desirable. According to Henss, these findings confirm the conventio- nal stereotype of attractiveness. Whoever is beautiful is also considered to be nice. By contrast, whoever is seen as ugly and unerotic, is neither nice. (Grammer, 1994; p. 151)

- The Female Face

In assessing female attractiveness the face plays a crucial role. No one would dispute this fact. But is there a precise formula for a beautiful face? How does one explain that in all cultures there is a consensus on whether these features are attractive or not? A few years ago, the ethologist Karl Grammer, who teaches in Vienna, was able to contribute to

clarifying these questions with an ambitious study (Gram- mer & Thornhill, 1993). He randomly selected sixteen por- traits of women from the composite computer image used by the police. (fig. 2) By superimposing these digitalized images he was able to compute an average face. (fig. 3)

In an experiment this prototype face was the one selected by most men and women as the most attractive face. It was even seen as being more beautiful than the most beautiful individual face. Since the images were superimposed, all individual features and irregularities vanished. Another factor is that the average face is more symmetric than the individual shots were. Thus the regularity and ‘averageness’ of facial features are what account for beauty. This study also revealed that it is mainly symmetry that determines wheth- er as face is seen as “erotic” or not.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

“Individual faces” “Average face”

In order to measure facial symmetry certain measurement lines were defined linking symmetric points on both sides. For example, the outer and inner corners of the eyes, the cor- ners of the mouth, the sides of the nose at its broadest point, the two cheek bones and the width of the cheek at the height

of the mouth corners. If a face is completely symmetric, there are no differences in the symmetric axes of these six measurement lines. In this case the axis would be a straight line. It is now possible to obtain a standard for asymmetry by determining the differences between the center points of the measurement line and the axis of sym-

metry and adding them. To make the individual faces comparable the result- ing figures must ultimately refer to the width of the face.

The red line in fig. 4 connects the central points of the measurement lines and shows the deviation from the axis of symmetry. (Grammer, 1994; p. 180)

- The Eyes

Fig. 4

The middle-point line

In addition to these standards relating to the face, there is literally a visual standard that has a bearing on attractiveness.

The human pupils appear as a black point in the middle of the colored iris. The openings become larger or smaller depending on the changes in the incidence of light. In glis- tening sunlight they shrink almost to the size of a pin head. Their diameter then totals about two millimetres. At dusk they expand about a fourfold of this size. The size of the pupil, however, is not just influenced by the incidence of light but also by emotional impressions. They can change their size also when the light remains the same. The change in the diameter of the pupil can be likened to a barometer of mood. If we see something that makes us happy or

frightens us, our pupils expand more than would be expect- ed given the prevailing light conditions. If we see some- thing that we don’t like or that puts a damper on us emo- tionally, the pupils contract more. Since this is also largely something that evades our control, the pupil’s size also reflects our real feelings. (Morris, 1978; p. 252)

The pupil signals are not just “emanated” unconsciously. Their reception is also an unconscious process. Even though serious research on the subject of pupil signals has only been pursued ever since the 1950s, this signal had already been conscious- ly manipulated much earlier. Centuries ago the courtesans in Italy had dripped poisonous belladonna in their eyes to widen their pupils. This way they wanted to enhance their beauty. Consequently, this plant was also referred to as

Belladonna

which in Italian means

beautiful woman

. Someone was seen as a Belladonna, beautiful woman, when she had other facial fea- tures in addition to the larger pupils: larger eyes, fuller lips, a narrower nose and pronounced cheek bones. The face on the right-hand side in fig. 5, which most people see as more attrac- tive than the left one, was modified by the computer to where it reveals the features as previously cited. (Kneissler, 2001)Fig. 5

“Belladonna” comparison

- The Figure

- The Waist-Hip Proportion

Another important factor of attractiveness is the

curve index

, i.e., the waist-hip proportion. It is generally assumed a large bust accounts for sex appeal. However, an analysis which compared the dimensions of the average German woman with those of a pin-up girl in

Playboy

(Grammer, 1994; p. 248) showed that this is an unfounded bias. The unexpected result was that the bust size of the pin-up girls was only 0.4 cm larger, while they had a 7.2 cm smaller waist and a 4.2 cm smaller hip! The two groups of women compared here thus revealed striking differences in the curve index. This fact explains why slimness is so desired and women invest so much in trying to live up to this ideal. A slim figure makes the curve index more obvious, thus producing more noticeable erotic signals. - The Pelvic Tilt

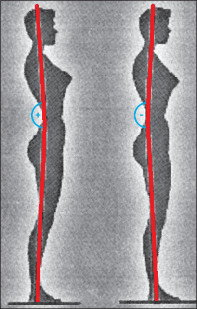

The factor that significantly influences the posture of women is the

pelvic tilt

, which is the tilt of the spine in the height of the promontorium towards the sacrum. From an anatomical perspective, the

promontorium

is the transition of the lumbar vertebra that juts forward into the pelvis at the upper edge of the sacrum. A change in this angle has two extraordinary results. On the one hand, it changes the entire muscular tension and thus the posture. Fashion capitalizes on this fact by offering shoes with high heels. When a woman wears high-heeled shoes the pelvic tilt becomes smaller towards the vertebralFig. 6

Pelvic tilt

column. As a conse- quence, the entire pos- ture becomes straighter which comes closer to an ideal of beauty than a “slouched” figure.

On the other hand, the result of a marked pelvic tilt is that the curvature of the body seen from the side is reinforced and is thus more conspicuous as an innate erotic signal. (Grammer, 1994; pp.

190-192)

- The Swaying of the Hips

Basically, we can say that each gender-typical difference can be turned into an erotic signal. One example is the gait, reflecting a different dynamic process in both man and woman.

Through human locomotion the woman’s buttocks become an erotic stimulus. The lateral swinging of the hips is seen as something typically female which men imitate when they want to emulate a woman or a “fay”. By contrast, men hard- ly show a swaying movement of the hips. (Grammer, 1994; p. 208)

- The Waist-Hip Proportion

- The Attractive Male Face

In the assessment of male attractiveness the face plays a somewhat different role. Grammer and Thornhill, who had already worked with images of women, randomly selected sixteen portraits of men from the composite image of a com- puter (fig. 7). By superposing these sixteen digitalized ima- ges they also computed an average face. (fig. 8) A study, however, showed that this average face was no longer select- ed as the most attractive one by both female and male test subjects. As a result of the superposition of the images all extreme features disappeared. The virtual face became well-proportioned and was thus seen as too “feminine”. (Grammer, 1994; p. 166)

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

“Individual faces” “Average face”

Through computer manipulation, the left and right picture of fig. 9 emerged from the average face in the middle. The authors of the study only expanded the lower jaw and extended the lower visceral skeleton in the right face. The opposite changes were performed with the left face. As a result of these manipulations the right face of the test sub- jects was assessed as being dominant, while the left one was

seen as subservient. (Grammer, 1994; p. 109)

Fig. 9

Comparison of male faces

The different facial forms have been used after Keating (et al., 1981) to assess a person as either superior (right) or infer- ior (left).

Other books

The Heat Is On (Boston Five Book 1) by Anderson, Poppy J.

A Hummingbird Dance by Garry Ryan

Rogue Dragon by Avram Davidson

the Plan (1995) by Cannell, Stephen

For Love Alone by Shirlee Busbee

Jason's Princess: A King Brothers Story by Elise Manion

Seduced by the Night by Robin T. Popp

Train's Clash (The Last Riders Book 9) by Jamie Begley

Fair Blows the Wind (1978) by L'amour, Louis - Talon-Chantry