She of the Mountains (7 page)

Read She of the Mountains Online

Authors: Vivek Shraya

In elementary school, he and his classmates drew the sun identicallyâan uneven circle in a top corner of the page with jagged triangles around the entire circumference, filled in with yellow crayon, and a smiley face drawn on it with an orange crayon. As she slept, he thought that, if he were to draw the sun now, it would be her face, not yellow but the colour of palaces in Jaipur. Her upturned lips that smiled even while she dreamed, not orange but the shade of eggplants, her crown of curly hair replacing the triangles, her eyes that were stars in their own right.

But why draw her face when I can look directly upon it?

he wondered. Instead, something about her face made him want to sing. This response was more concrete than melody; it was a lyric too. A melody that had not yet been sung and a lyric not yet written.

Quietly humming, he followed the lines of her neck down to her shoulders, clasped by his hand, his arm around her back, their bodies held together by her white sheets. If he squinted slightly, together they appeared to him like a sea of brown rolling over and under white clouds.

He remembered trying to figure out what kind of brown she was when they first met. The shape of her nose gave away her Muslimness, but he wondered what type of brown girl wore khakis and had a crush on Data from

Star Trek

. He took clues from her closest friends when they visited her at work. They were

Brown Girl

brown; their approach to style, acquired mostly from Dynamite, Garage, or Forever 21, involved showing various degrees of skin and yet always appearing business-casual,

as though they weren't able to completely shed their parents' traditionalism. They were professionals who dated only Muslim brown men and went to clubs that played hip hop music infused with some Bollywood. She really liked that one Nelly Furtado song.

He was in a brown category that was generally frowned upon by other brown people, especially other brown parents:

Alternative brown

. This meant he wore vintage clothing, had his ears pierced, had blond streaks, and hung out with non-browns.

In some ways, he was more brown than anyone he knew. When given the choice of restaurants to go to on his birthday, his craving for deep-fried cheese cubes mixed with peas trumped burgers or pizza. He listened to santoor on Saturdays when he cleaned his room and understood the complicated, often multi-storied significance behind most Hindu celebrations like Deepavali and Onam. He thought Sanskrit was the most beautiful language he had ever heard and found the constriction of English translations, which exposed the general apathy of English itself, deeply disappointing. “Prema” was so much more expansive and sacred than “love.”

And yet, brown in and of itself, had not yet registered as a real colour to him. Brown was unremarkable, a non-colour, akin to a shade of grey. For he had been blinded by another colour: white. White expanded limitlessly and drained every other colour out until all that could be seen was

whitefriendwhiteactorwhiteteacherwhiteneighbourwhiteinventorwhitestrangerwhiteactresswhitecoworkerwhitesingerwhiteprincipalwhitefriendwhiteactorwhiteteacherwhitecashierwhiteneighbourwhitestrangerwhiteserverwhitepostmanwhiteclassmatewhitebullywhiterockstarwhitefriendwhitefriendwhitekingwhitequeenwhiteteacherwhitemodelwhiteconquererwhitesaviourwhitewomanwhiteprimeministerwhitedoctorwhiterealestateagentwhiteneighbourwhitefriendwhiteprofessorwhitegodwhiteairstewardwhitemanwhitescientistwhitedentistwhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewwhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhitewhite

White was almost every interaction he had, and through this relentless exposure, he learned to value it, serve it, aspire to it, his white bedroom walls plastered with white famous faces. This was where the true power of white resided.

But something unexpected happened when he placed his brown next to hers, something that white worked so hard against.

whitewhitewhitewhite

Â

brownbrown

Â

whitewhitewhitewhite

In the absence of white, he could see colour.

Your brown has more of a pink base than mine,

he had observed the first time they held hands, still looking for answers to her origin in her skin.

It's true. And your brown has a yellowy tone to it,

she said.

I look jaundiced?

She laughed and shoved him gently.

No, no. You are golden.

I am also darker than you â¦

Your skin is perfect. Why would anyone want to be another colour?

She kissed his cheek.

Marvelling at her perfectly round chestnut cheeks, he couldn't

help but agree. Falling in love with her brown had unexpectedly given his own skin new value, a new sheen.

As they dug past the surface, they discovered their brownness was a map that only directed them closer, pointing to their abundance of commonalities and fascinating variations. She called lentils “dhar,” he called lentils “dhal.” His motherland was India; she was a child of the Ismaili diaspora. She couldn't do a brown accent; he sang her songs in Kannada. Through these travels, they created a whole new shade of brownâtheir shadeâone that beamed gloriously in the beauty of itself, one that hadn't been taught that it was anything less than extraordinary.

As she woke up to his face, she spoke softly in Khatchi:

Aau thoke bo arathi.

What do you like about me?

The question was unexpected. On its own, it implied an insecurity, forcing the other person to respond with a list of compliments:

You are intelligent,

Â

sexy,

Â

hilarious,

Â

adventurous,

Â

thoughtful

â¦

Fishing was not her style, but before he responded he found himself envious that he hadn't thought to ask the question himself.

Everything.

He put his hand over her hand.

That's not an answer.

She pulled her hand away.

But that's my answer.

He didn't know how to say in words that she was the first person he had ever liked outside of his needs. He didn't like her because she was another person whose approval he craved or merely

because she liked him back. He liked her for herself and everything she embodied.

But even more than thisâbefore her, he hadn't known how to trust love because he had always had to work for it. Every smile, phone call, birthday gift, he had fought for. Put out his neck for. Stood in the rain for. Earned with muscle and memory. He noticed the details no one else paid attention to, remembered the occasions that everyone else forgot, weathered rejection or no response at all, found a void, and then found a way to fill it.

So when someone had said

I need you

, it just meant he had been successful. If they didn't need him, he hadn't bent low enough, gotten on his knees, and his skin hadn't developed the right callouses.

When they said

I miss you,

it just meant that they were responding to the gaps between his carefully timed, repetitive appearances in their inbox or on their doorstep.

And when they said

I love you

, he wanted to respond:

You should

. And then walk away.

But not with her. With every step he had taken toward her, she had taken a step toward him.

His hand reached for her hand again.

No, really, what do you like about me?

she insisted.

Why?

I figure if I know, I can keep doing it to keep you for as long as I can.

The birth of my second son, Muruga, has healed our familial wound. He is a new beginning for us, a new and unsullied body at whom to direct our love, reflecting back the best in all of us. So content are we to be in each other's company that we seldom leave our abode.

Shall we play a game, boys?

Shiv asks.

Muruga jumps up.

Yes!

Okay. Whoever is the fastest to circle the earth three times will receive a special blessing from your mother and me

, Shiv says.

Shiv, you know we love our boys equally.

Muruga hops on his peacock vehicle and bolts off without hearing my admonishment.

I know Shiv has to be jesting about the reward, but Muruga has the advantage. Comparisons have been made between Muruga and Ganesh in the celestial and human worlds, and it is clear that Muruga is everyone's favourite. Is this because of Ganesh's now even larger physicality? Although he is perfection to me, I recognize that, of the main deities, he lacks an immediate prettiness. His skin isn't the colour of the sky. He can't be beautified (or hidden) by flower garlands. His presence is unabashedly what it is. Isn't that what divinity should be? The embodiment of truth?

I turn to Ganesh, who is slowly rising to his feet.

Your father is being silly. You don't have to play.

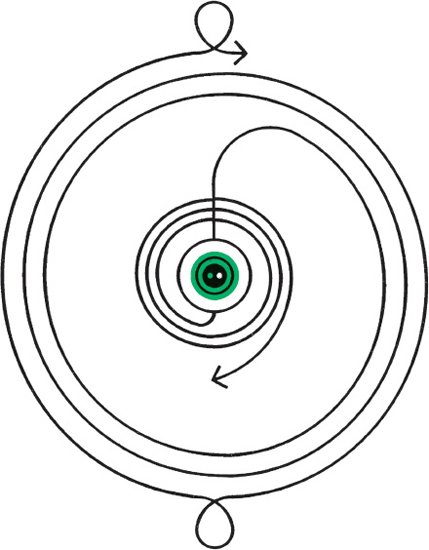

He doesn't respond. Instead, he walks solemnly toward where Shiv and I are seated, leaning on each other, and begins to circle us in silence.

Ganesh, what are you doing, son?

After three rounds, he finally responds, panting.

Dearest Uma and Pita ⦠you are my earth. You are my world.

I put my hand on my chest and sigh. Shiv stands to embrace Ganesh.

Oh, beloved son. You have demonstrated how a loving heart and a wise mind can surpass any physical prowess. From this day forward, no prayer or journey may commence without acquiring your blessing first. I name you Lord of the Lords.