Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (17 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

One more picture did the trick. This portrait, titled

Mosa,

shows a Mojave girl in early adolescence. She is a face-painted beauty with a careless

gaze, skin as smooth as a bar of soap—just the jewel for Morgan the collector. He

loved the picture, and it sealed the deal. Very well:

“I will lend financial assistance for the publication of a set of books illustrated

with photographs such as these,” Morgan said. Yes? More Mosa, in other words. Curtis

assured him there were many more Mosas where that came from. Now, had Curtis heard

him right? A deal was done, just like that? Indeed he had. “My staff will take care

of the financial arrangements.”

Morgan agreed to the $75,000, spread over five years—for fieldwork only. The money

for publication, the printing and binding, would have to come from those willing to

pay the subscription for the complete twenty-volume set. And $5,000 was too much to

ask. How about $3,000 for a set printed on thick etching stock, and $3,850 for Japanese

tissue? And instead of one hundred sets, why not try to sell five hundred sets? A

superb idea! The books must be bound in lustrous leather. Of course! Beautiful to

behold, a thing of great artistry. Done! There remained one quibble about the text.

Rather than hire some eminent scholar for the prose narrative, or a ghostwriter with

many books already published, why not have Curtis write it himself? After all, who

better knows the Indians? He had promised in his outline to produce “interesting reading,”

had he not?

“You are the one to write it,” Morgan said. “You know the Indians and how they live

and what they are thinking.”

They shook hands. The photographer gathered up his material, closed his portfolio,

turned to leave. “Mr. Curtis,” Morgan said in closing, “I like a man who attempts

the impossible.” By then, Curtis had forgotten about the nose.

For days, Curtis strolled on air. No January looked so good. No city so great as New

York. No man so wonderful as J. Pierpont Morgan. “I walked from his presence in a

daze,” he said. Yes, $75,000 was a trifle compared to the nearly ten times that amount

Morgan had spent on the musty book collection of a Brit. But to Curtis it was everything—his

life work, his future. Clara was with him, getting a rare chance to share a triumph

with her husband. For the moment, he did not care about the details of selling individual

sets, on spec, for an amount equal to three times the annual wage of an average American.

Nor did he seem concerned that he had cut himself out of a salary. What he rejoiced

at was the assurance of $15,000 a year, enough to bring the Big Idea home and establish

himself among the greats who strived to capture human images for posterity.

MORGAN MONEY TO KEEP INDIANS FROM OBLIVION

Morgan got the kind of press he wished for, the historic irony lost on the daily papers.

But before the headlines, Curtis told Roosevelt of his triumph.

“I congratulate you with all my heart,” the president replied in a short note. “That

is a mighty fine deed of Mr. Morgan.” And to this Roosevelt added a surprising request.

His daughter Alice, the most celebrated young woman in America, would be marrying

shortly. Yes, Curtis knew: it was in the press every day, the upcoming nuptials between

a handsome congressman, Nicholas Longsworth, and Princess Alice. Roosevelt asked Curtis

if he would photograph the event. Everyone in the country would want a look, and what

they would see would be filtered through the lens of the Shadow Catcher.

Near the end of the summer, after Morgan’s first check had been cashed, after the

wedding pictures of the first family had gone out to wide acclaim, after Curtis had

put together a staff of top-drawer talent, the photographer wrote Roosevelt to ask

a favor of his own. He was deep in Indian country, composing a note from the Hopi

homeland. The work had gone very well, he reported: he expected to publish the first

two volumes within a year. He’d made a major breakthrough with the Apache. He was

closer than ever to the Hopi. And he felt he knew enough about the Navajo to tell

a word-and-picture story without precedent. He was fascinated by the Zuni; the pueblos

of New Mexico Territory were a photographer’s dream. He wondered if the president

would be willing to write an introduction to the work, something along the lines of

the earlier letter of endorsement Curtis had circulated while looking for a benefactor.

“Pardon my crude way of saying it,” Curtis wrote, “but you as the greatest man in

America owe it to your people to do this.” Such nerve. But Roosevelt couldn’t resist.

He replied from Sagamore Hill, saying he was honored that Curtis had asked him to

pen a few words on his behalf.

“Now I so thoroughly sympathize with you in your work that I am inclined to write

the introduction you desire,” Roosevelt wrote. “But how long do you wish it to be

and when do you wish me to have it ready for you?”

The year closed with Curtis at his happiest. He not only had the patronage of the

most powerful banker on the planet, but the president of the United States was working

for him as well. For free.

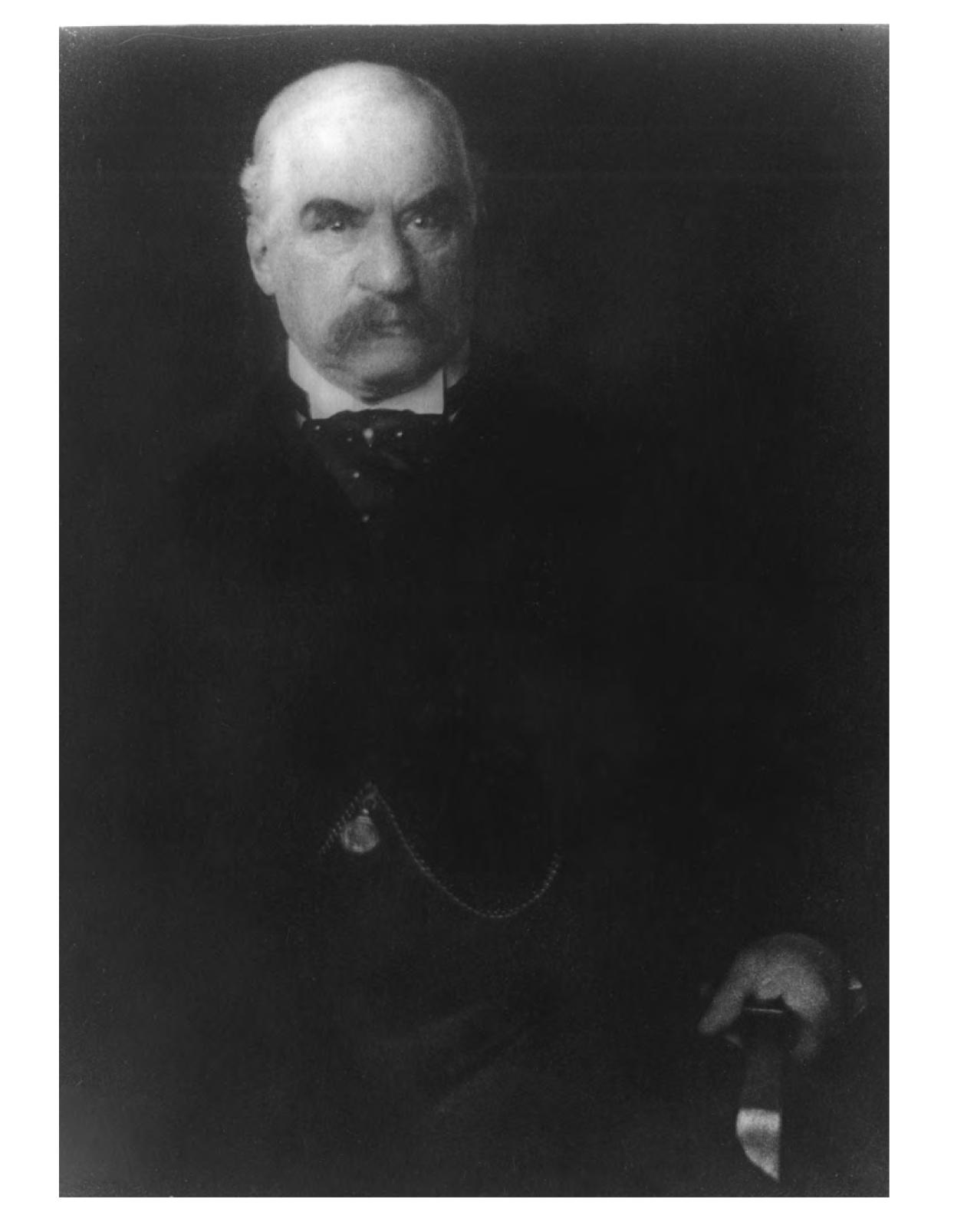

richest banker in the United States, taken three years before Morgan agreed to back

the Curtis project. The light glinting off the armrest was seen by many viewers as

a knife.

1903. This is the picture that won over Morgan, who at first was reluctant to help

Curtis.

kept her personal life secret, shedding one racial identity for another.

1906

W

HEN HE RETURNED

to the White Mountain reservation in late spring of 1906, Curtis was determined to

stay until he could decipher the inner lives of the Apache. He had with him a paid

crew this time, and enough cash to be a bargaining force among people who had shunned

him earlier. He would not leave, he insisted, until the Great Mystery was evident

in his pictures and understandable in his words. Three days out of Seattle, he arrived

at the rail stop of Holbrook, a dust-choked trading town along the anemic Puerco River,

just downslope from the Apache homeland in the mountains of eastern Arizona Territory.

Though the days were long under the glare of an unblinking sun, winter still had a

grip on snow-covered peaks of ten thousand feet or more. Roads were half built, washed

out in places, mere rumors in others. Six years before Arizona became a state, portions

of it were terra incognita to the outside world. In advance of the trip, Curtis had

written the Smithsonian wondering if someone could send him “an available map there

in Washington which gives a good detail of that country.”

Upward the Curtis party marched, a dust cloud around a wagon pulled by four horses,

upward to piñon-covered prickly ground, through an area known as the Petrified Forest,

winding and stumbling in search of faces to fill Volume I of the series that would

soon be formalized under the title

The North American Indian,

with an office (for selling subscriptions) in New York, at 437 Fifth Avenue. For

the first book, Curtis had chosen the Navajo and the Apache, two tribes that had most

enchanted, and eluded, him.

Curtis did not lack internal fuel: he wanted to show Morgan and Roosevelt that he

could live up to their trust, but he also wanted to prove to the credentialed Indian

experts that their ignorance was stupefying.

“You are going to get something that does not exist,” an Indian scholar had told Curtis

in Washington, D.C., a few months earlier. “The Apache have no religion.”

“How do you know they have no religion?” Curtis replied.

“I spent considerable time among them, I asked them, and they told me . . . You’re

wasting your time.”

The money from J. P. Morgan allowed the photographer to stock his project with a first-rate

posse, building his team one at a time in the months after leaving Manhattan. His

closest aide was an ex–newspaperman of multiple talents, William E. Myers, who was

twenty-eight years old when he fell under the spell of the Shadow Catcher in 1906.

Like his boss, Myers grew up in the Midwest; unlike him, he had a pedigreed education,

majoring in Greek on his way to graduating with honors from Northwestern University.

He spoke several languages, and had been raised in a middle-class family that valued

learning. An uncanny linguist, Myers had an ear for the nuances of speech and dialect,

which was vital to the groundbreaking work that Curtis aspired to do. In addition,

his swift shorthand proved invaluable in taking down words for the dictionary-like

glossaries Curtis was pulling together of languages that were falling out of use.

Myers had taught school in the Midwest, then worked at the

Seattle Star,

a gritty daily, before signing on with the open-ended adventure of Edward S. Curtis.

“To the Indians, his skill in phonetics was awesome magic,” Curtis wrote of Myers.

“In spelling, he was a second Webster.” Equally important, he had the stamina and

stable personality for a project that would allow no room for a private life, let

alone sleep.

Myers was two years older than Bill Phillips, who had been working for Curtis since

his student days at the University of Washington. Now twenty-six, Phillips had become

a jack-of-all-trades for the Indian enterprise. He would find translators, arrange

for food and transport, set up portrait sessions and locations for outdoor shoots,

smooth disagreements and take copious notes. Phillips was in awe of Curtis, impressed

by the audacity of his leaps to the upper reaches of American society and by the vision

of the Big Idea. Rounding out the traveling crew was at least one translator, depending

on the tribal band, and a steady cook named Justo, who had the added skill of being

a horse wrangler.

Outside the field team, Curtis made one other hire that year, a plum for him: Frederick

Webb Hodge, a Smithsonian ethnologist and scholar of American Indians. Curtis had

been courting him for three years. English born, Hodge was trained as an anthropologist

and historian but did his best work applying authoritative polish to other people’s

words. He was forty-one when he agreed to become the long-term editor for Curtis,

at $7 per thousand words. He would also keep his day job at the Smithsonian, where

he was overseeing

The Handbook of American Indians,

considered the definitive guide in the field. Unlike other Washington experts, Hodge

had visited tribal lands—Acoma, the Navajo reservation, the Zuni Nation—many times.

To have the prose of a self-educated photographer acquire the imprimatur of Hodge

assured Curtis that the most ambitious literary undertaking of the new century would

not be easily dismissed in learned circles.