Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher (19 page)

Read Short Nights of the Shadow Catcher Online

Authors: Timothy Egan

Curtis tried a preemptive move: he used his influence with Francis Leupp, the commissioner

of Indian affairs, to arrange letters of transit, sent by telegram. Once these documents

arrived, Charlie Day and the Curtis party moved down into the thirty-mile-long Canyon

de Chelly for an extensive field session. Day had been appointed by the U.S. Department

of the Interior as a guardian of Anasazi treasures, and knew every wrinkle of the

canyon. Vandals and thieves were actively chiseling away the centuries of life left

behind in the cliffs. The stone apartments cut from the rock, so well preserved by

the protective canyon walls, looked as if their inhabitants had gone only days ago.

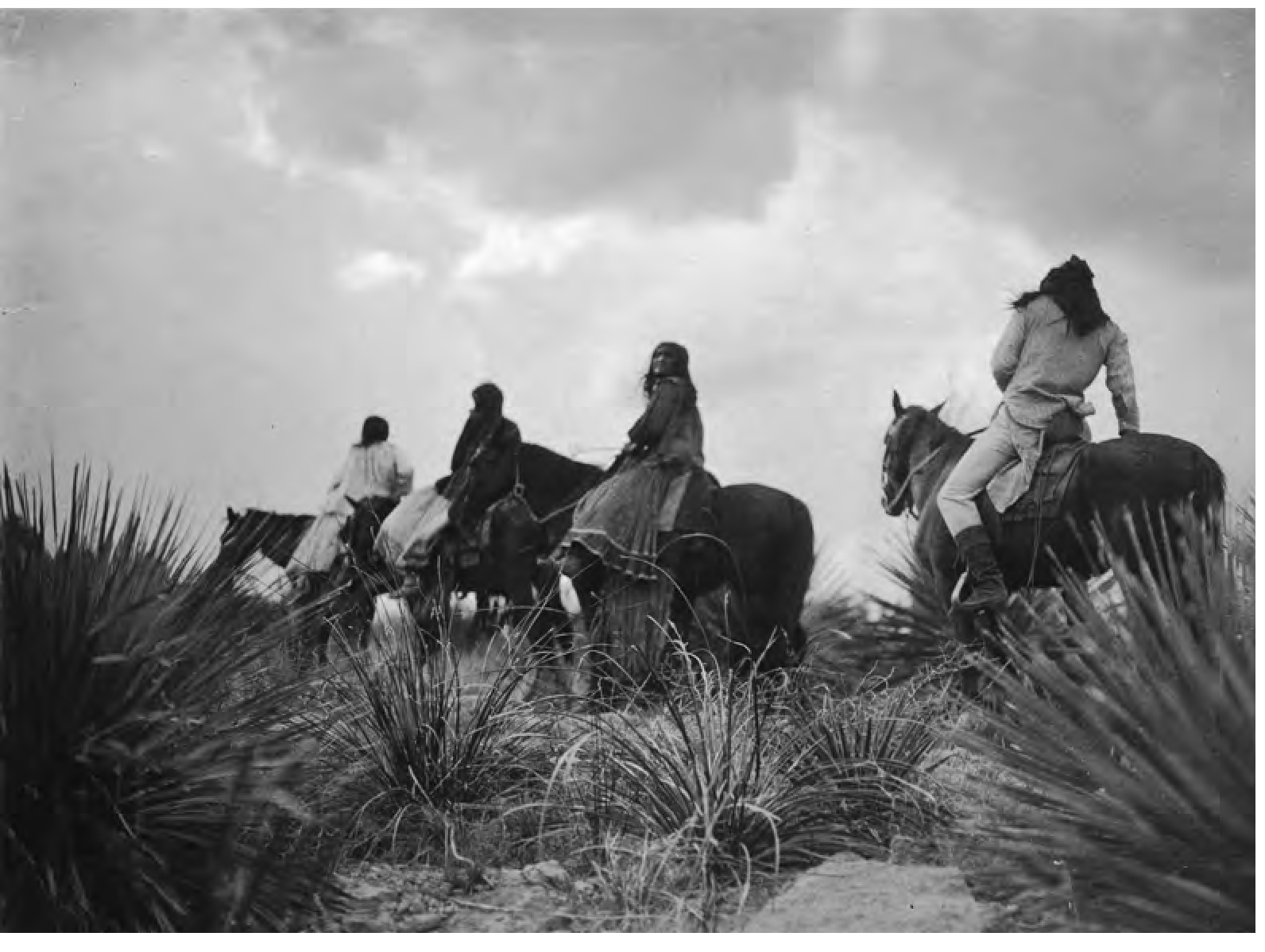

Curtis already had much of the material he needed for the Navajo section of Volume

I; a picture he had taken of Indians moving through the canyon two years earlier was

being hailed as a masterpiece. When John Ford went to Monument Valley some thirty

years later to shoot the first of his greatest westerns, he was building on the images

Curtis had produced in the Navajo living room: people dwarfed by cloud-piercing rock

walls and spires in the open West. On the 1906 trip, Curtis was looking for just enough

to fill out the rest of the first book, with Day helping to find subjects. “We made

camp in an oasis under cottonwood trees,” Curtis wrote, and then cast about in search

of faces that matched the terrain.

The sky was alive on those summer days. Afternoon temperatures of 105 degrees were

broken by electric storms and flash floods, the warm-season monsoons of the Southwest.

For the Curtis family of five, together at last in common purpose, the hours went

by at a pleasant pace. Florence was impressed by her father the cook, who would procure

fresh-butchered lamb from the Navajo and grill chops and corn over an open fire. With

this meal he usually served squaw bread made by people in the canyon. On days when

Justo wasn’t up to it, Curtis would prepare a big feast from scratch for the entire

team, including any natives who happened to be around. Their camp was always full

of Navajos, the women in rippling skirts and blouses made of velvet, the men with

bright scarves and thick, buckskin-soled shoes. “The Indians laughed inside and out,”

Curtis said, reflecting the joy he felt. Several hundred people lived full-time in

the canyon, tending to gardens watered by freshets from the thunderstorms, while others

moved through seasonally, in search of forage for sheep.

The Curtis children were fascinated by the turquoise jewelry makers, the rug weavers,

the sheepherders, the storytellers, the colors and sounds of the canyon, with its

sun-burnished walls of stone, the flanks streaked ocher and rust from the mineral-rich

water. The girls wore sun hats and frocks; Hal was dressed like a cowboy. They rode

mules and horses, collected horned frogs and small lizards, chased jackrabbits. They

climbed the cliffs with Charlie Day and their father to get a peek at those haunted

stone neighborhoods which had been abandoned eight hundred years earlier, and tried

to decipher petroglyphs, some dating back nearly three millennia. In their eyes, the

Shadow Catcher was the field general of all human activity in Canyon de Chelly. He

worked the audio recording machine, with Myers taking shorthand. Songs, legends, words

were catalogued. Curtis spoke enough of the language to force a smile from an old

native. As a horseman and a cliff climber, he was a springy athlete. And the things

that went on in the heat of the afternoon inside the tent—a makeshift studio—were

magical.

He took pictures not just in the low-angled light of dawn and dusk, when “nearly right”

was easy enough. Each hour of the sun could produce a different effect. He waited

for opportune weather. And he never used a flash, at least not in the Southwest. “Conditions

cannot be changed,” Curtis explained. “I must fit myself to them.”

One day in August, the canyon suddenly emptied of Indians, and a stillness fell over

the big crack in the earth. Charlie Day told the family to stay close to camp and

await his word. At night, the children heard chants bouncing along the thousand-foot-high

walls around them. The chants lasted till dawn, though they saw no people. Curtis

was at a loss to explain. When Day returned late at night, he said they were in trouble—they,

the Anglos. A woman was trying to give birth not far from the Curtis encampment, but

it was going badly. She was deep in labor, in terrible pain, bleeding profusely, but

the infant would not emerge. Medicine men were summoned. They tried traditional remedies,

to no avail. Then the Indians diagnosed the problem: it was the presence in the canyon

of white people taking pictures. Curtis immediately woke his family and started heaving

gear into the wagon. He told them they must leave immediately.

Groggy children snuggled in the wagon, their mumbled questions met by a shush from

their father. Horses were hitched in the dark as the chanting continued.

Flee,

Charlie Day ordered—quickly and quietly, and do not make contact with anyone along

the way.

“Pray the baby will live,” said Day. “There is no power on earth that will save you

and your family if it should die.”

He was exaggerating, surely, but as a cautionary measure. For the first time in nearly

eight years of concerted forays into Indian country, Curtis felt helpless and afraid,

at the mercy of his photo subjects. The family rode out of the canyon, a long, tremulous

climb, and made their way to Chinle, where word came through Day’s contacts that the

baby had lived. But what had started so blissfully for the family now broke down in

a prolonged spat between Curtis and his wife. The children’s lives had been put at

risk. How could he have done that? Great Mystery indeed. What did he really know about

these people? Curtis had no answers; it was a freakish thing, forget it. They would

reassemble again in another part of Indian country, next year, and the year after.

Let’s not let this one episode ruin the good days. But Clara was adamant: never again

would the entire family travel to Indian land. With the start of school approaching,

Clara and the children left for Seattle. Curtis stayed behind.

“Everything has to be kept on the move,” he said.

On to Third Mesa, in the Hopi Nation, where Curtis was in search of the Snake Society

once more. Crossing scabbed and pockmarked tableland in late summer was full of peril.

Washes, often bone-dry, could fill with red water in a flash, enough to float the

wagon. Coming from the maritime Northwest, where rain fell as soft and persistent

mist, Curtis was not used to such muscular meteorological mood changes. “The rain

pours down,” he said. “What was an arid desert when you made your evening camp is

soon a lake . . . And then comes the sand storm. No horse can travel against it. If

en route you can but turn your wagon to one side to furnish as much of a wind break

as possible, throw a blanket over your head and wait for its passing. It may be two

hours and it may be ten.” Overall, though, joy outweighed the misery. And when he

arrived at Old Oraibi, after a half-dozen previous visits, Curtis was greeted with

smiles from familiar faces—and a major piece of good news. On an earlier trip he had

been allowed to film the Snake Dance from a rooftop. Now Sikyaletstiwa agreed to let

him participate in that most important, extended prayer for water. He could go with

the priests to the fields to gather diamondback rattlesnakes, bring them to a kiva

and tend them, and be a part of the culminating dance.

There was some calculation on the Hopi side. It had been a summer of unrest, with

missionaries stepping up pressure to end the ritual and send Hopi children to a Christian

school. As it was, the Tewa and Hopi people who lived on the reservation felt overwhelmed—and

certainly surrounded—by the much larger Navajo population. Enlisting Curtis, at the

height of his influence, could help the cause of the traditionalists. During his visit

in 1905, Curtis had heard that members of the tiny Havasupai band to the north were

dying of hunger. He promptly sent word to Commissioner Leupp in Washington, and starvation

was averted (though tribal members continued to die from measles).

Curtis agreed to meet all requirements, and to perform his duties without balking.

First came days of fasting, to purify himself. Then the priests stripped and painted

their bodies in preparation for the snake hunt, which lasted four days. Those early

hours in the field, Curtis faced a trial that would reveal the depth of his dedication.

As the new priest, Curtis was told that he had a special task: to wrap the first captured

snake around his neck. It was tradition, or so they told Curtis. The Indians picked

up a big rattler and extended it to him. The snake hissed and bared its fangs, the

scaly skin touching the sun-bronzed neck of Curtis. He remained motionless, steeling

himself for the tightening around his throat, trying not to scare the rattler into

biting him. After a few long minutes, the snake uncoiled and was removed from his

neck. Curtis had passed his first test.

What he knew already was that the actual nine-day ceremony wasn’t so much a dance,

as it had been advertised by outfitters and the rail lines that brought tourists to

witness the public part of the spectacle, but “a dramatized prayer,” in Curtis’s words.

To the Hopi, snakes were messengers to the divine. The priests of the Snake Dance

order were the facilitators. In the kiva, the curling and hissing rattlers were washed

to make them clean for the Hopi prayer. For nine nights, Curtis slept within a few

feet of the snakes, either in the kiva or on the rim of the dugout home. On the day

of the big dance, a congregant smeared paint on his cheeks, his forehead, his neck,

chest and back. He removed all his clothes and dressed in a simple cloth covering

his genitals. Crowds massed along the edge of the village, tourists and natives, ten

deep in places. The snakes were lifted from the kiva to a central place. The crowd

moved in tighter. Priests began to dance, picking snakes as partners, singing prayers

and incantations. Curtis, waiting in the wings, held back, hiding from view. At the

last moment, he balked. He knew the audience was stocked with missionaries and government

agents; he could tell by looking at them, taking notes for possible prosecution. He

recognized Anglo faces. His presence, the great Shadow Catcher, the first white man

ever allowed to participate as a priest in the Snake Dance order, would be widely

disparaged in official circles and reported in the popular press. After six visits,

over six years, studying and photographing every part of the ceremony, getting to

know the religious leaders and then becoming a priest himself—at this culmination

of his quest he worried that, should he take the final step, he might undermine the

most significant event of the Hopi religion.

“I was fortunate enough to be able to go through the whole snake ceremony,” he wrote

his editor Hodge, “. . . in fact doing everything that a Snake man would do except

take part in the Snake dance. The only reason I did not do this was because I feared

newspaper publicity and missionary criticism.” He was also troubled by the earlier

events of the summer. What had happened to Goshonné, the Apache medicine man, after

he had spilled the secrets of the tribe’s creation myths, and the scare of the last

day in Canyon de Chelly, had told Curtis much about the balancing act of his work.

He had gone deep into the culture of a people that Americans had never understood,

deep enough to realize—even at this moment of triumph—that there were places where

he did not belong.

1906. In the arid high country of Arizona Territory, Curtis spent many months trying

to capture Apache moments. Told the Apache had no religion, he was determined to prove

otherwise.

1907

C

URTIS WINCED AT

the stabbing questions of a writer facing the most terrifying of prospects: a blank

page. Where to begin? How to tell the story? What exactly was he trying to say? Had

his sole job been the photographer assembling an epic of images, it would have been

much simpler. But words were something else. He’d been published in

Scribner’s,

yes, and a handful of other magazines, and had given enough lectures to be confident

he could hold an audience rapt. With the first book, he had to reach for something

sturdy and authoritative, and that realization brought on writer’s block. As Morgan

had said, he was best suited to put down the words; he was the “photo-historian,”

so called by the newspapers, a dual responsibility—too much, perhaps. He forced pen

to paper now under the lengthening shadows of thick oaks in Arizona, late in a season

that had taken him from the Apache homes in the White Mountains to the Jicarilla Apache

communities in New Mexico, with numerous other stops in between.

THE NORTH AMERICAN INDIAN

Being a series of volumes picturing and describing

the Indians of the United States and Alaska, written,

illustrated and published by Edward S. Curtis.