Signor Marconi's Magic Box (13 page)

Read Signor Marconi's Magic Box Online

Authors: Gavin Weightman

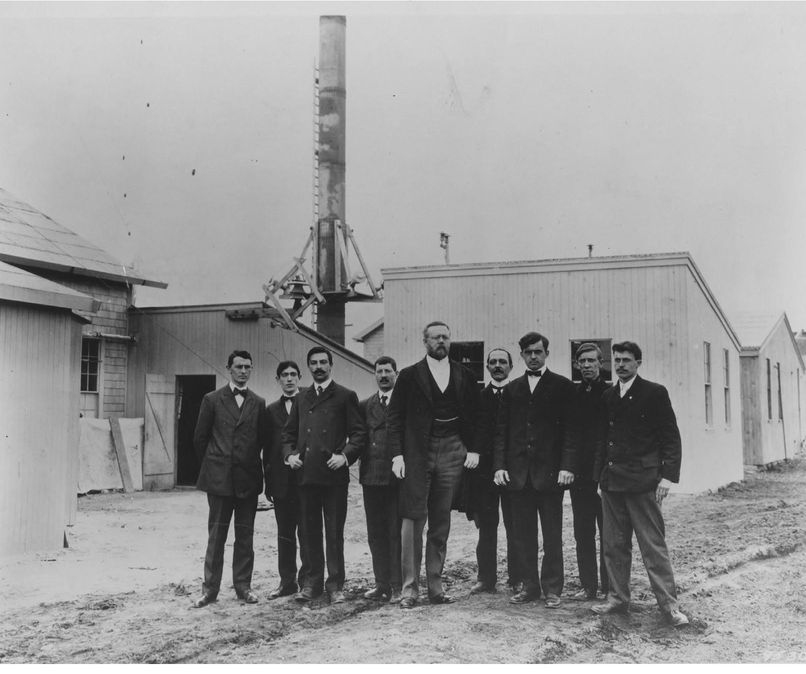

One of Marconi’s most talented rivals, the Canadian Reginald Fessenden (centre, with spectacles and watch chain), towering above his assistants at his remote research station at Brant Rock, Massachusetts. It was from here at Christmas 1906 that Fessenden, backed by American financiers, made the first-ever voice broadcasts by wireless. He was disheartened when nobody took any interest in his achievement.

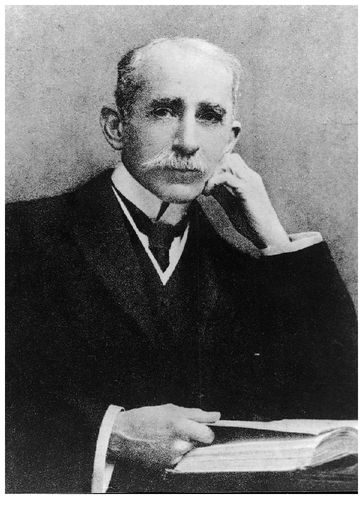

Ambrose Fleming, the diminutive and slightly deaf London University Professor who was employed by Marconi’s company as a consultant during the crucial years when the first wireless signals were sent across the Atlantic. Fleming’s expertise was needed to build the powerful transmitter, and in 1903 he invented the first primitive radio ‘valve’, adapted from a vacuum lightbulb.

George Kemp had salvaged a small station from the east coast of England and brought it to within a few miles of Poldhu, at the southern tip of the Lizard peninsula. Marconi carried out tests to discover whether the signals from the much more powerful Poldhu transmitter would interfere with those at the Lizard if the two were tuned to different wavelengths. There appeared to be no problem, and while Poldhu was being tested the little Lizard station began to set new distance records, making wireless contact with a second Marconi station on the Isle of Wight at Niton, 186 miles away. Only occasionally did the locals take any interest in what was going on at Poldhu. On 30 May the

Royal Cornwall Gazette

carried a paragraph: ‘Mr Marconi accompanied by his private secretary Prof Fleming and several other gentlemen connected with the wireless telegraphy company are staying at Poldhu Hotel, Mullion . . . and from the activity shown it is believed that important experiments are contemplated.’ The notion that a distinguished London University Professor was Marconi’s ‘private secretary’ would have caused amusement in the academic world.

Royal Cornwall Gazette

carried a paragraph: ‘Mr Marconi accompanied by his private secretary Prof Fleming and several other gentlemen connected with the wireless telegraphy company are staying at Poldhu Hotel, Mullion . . . and from the activity shown it is believed that important experiments are contemplated.’ The notion that a distinguished London University Professor was Marconi’s ‘private secretary’ would have caused amusement in the academic world.

If asked, the engineers at Poldhu would say that their ‘important experiments’ were entirely to do with contacting ships at sea which had been fitted with wireless cabins. The same answer was given to any inquisitive visitors to the station at Cape Cod, and it made perfect sense: there would have to be shore stations on both sides of the Atlantic to make contact with liners if the range of wireless was indeed limited to a couple of hundred miles. It was believed that only very long wireless waves could travel great distances, and that for a signal to cross the Atlantic a charge to the tall aerial

towers had to be delivered by a giant version of Marconi’s early spark transmitters. By the summer of 1901 Professor Fleming was generating huge sparks at Poldhu that produced thunderclaps which rolled along the Cornish cliffs and echoed in the coves.

towers had to be delivered by a giant version of Marconi’s early spark transmitters. By the summer of 1901 Professor Fleming was generating huge sparks at Poldhu that produced thunderclaps which rolled along the Cornish cliffs and echoed in the coves.

After his return from Cape Cod, Marconi spent most of the summer experimenting at Poldhu, while Kemp continued to struggle with the aerial. There was little time for relaxation, and Josephine Holman was beginning to indicate in her letters that her fiancé’s long absences and silences were troubling her. An anecdotal story, told years later to Marconi’s daughter Degna, has Marconi taking part in a local cricket match at Mullion, perhaps as a member of one of the scratch teams sometimes put together by the guests at the Poldhu Hotel. Sadly the scoresheet is lost, and there is no record of how Marconi, in all other respects the perfect English gentleman, fared with the unfamiliar willow bat and red leather ball.

On Sunday, 15 September George Kemp had a day off, and walked the short distance along the coast to Gunwalloe church for the service. The next day the strong winds and rain made outside work difficult, and Kemp recorded in his diary that he had struggled to keep the masts upright. On Tuesday, 17 September a gale blew in the morning while they were testing different methods of creating sparks. The wind had been from the south-west, but at one o’clock in the afternoon it veered to the north-west, and a sudden squall ripped at the rigging, tore out the supports of one of the masts, and the whole lot collapsed. It was fortunate that nobody was injured. Surveying the wreckage, Marconi asked Kemp to start rebuilding, but to a less complex model. He then took the horse-bus to Helston station and returned to London. He needed to persuade the board members that his plans would have to change. The replacement Poldhu mast would be more robust, but would not have the power of the one that had collapsed. Cape Cod was too far away, and a point on the North American coast closer to Cornwall would have to be found. Wherever that was to be, there would be no time to build a transmitter or even much of a receiving

station if Marconi were to achieve his ambition before the end of the year.

station if Marconi were to achieve his ambition before the end of the year.

To get around the steep, narrow lanes of Cornwall and to speed up his frequent trips to Helston station from the Poldhu Hotel, Marconi had delivered from London a new-fangled machine, a motorbike with an engine mounted over the front wheel. It arrived in kit form, and Kemp helped him assemble it. The sense of urgency at Poldhu was growing every day, as Marconi feared that one morning the newspapers would announce that some other ‘wireless wizard’ had outdistanced him and stolen his thunder.

13

An American Forecast

W

hile Marconi was enjoying international fame in 1900, a more seasoned but lesser-known inventor had set up a primitive research station on Cobb Island in the Potomac River, Maryland. Reginald Fessenden, his wife Helen and young son lived a very simple life on the island. With meagre funds, they could not afford the luxurious hotel accommodation Marconi enjoyed. The Fessenden family and their researchers had no running water, and their greatest culinary delicacy was the occasional delivery of oysters brought by a local sea captain. Their remote research station was plagued by insects in summer, which did nothing to soothe Fessenden’s notorious fits of temper when his attempts to develop his system of wireless telegraphy were frustrated.

hile Marconi was enjoying international fame in 1900, a more seasoned but lesser-known inventor had set up a primitive research station on Cobb Island in the Potomac River, Maryland. Reginald Fessenden, his wife Helen and young son lived a very simple life on the island. With meagre funds, they could not afford the luxurious hotel accommodation Marconi enjoyed. The Fessenden family and their researchers had no running water, and their greatest culinary delicacy was the occasional delivery of oysters brought by a local sea captain. Their remote research station was plagued by insects in summer, which did nothing to soothe Fessenden’s notorious fits of temper when his attempts to develop his system of wireless telegraphy were frustrated.

Fessenden was eight years older than Marconi, and a much more experienced experimenter. Born in 1866, the son of a Canadian Anglican minister, he had spent much of his youth close to Niagara Falls at the time when it had first been used for the generation of electricity. He studied mathematics and sciences, but did not finish any course which would have given him a formal qualification. As a teenager he took a job as a teacher in Canada, and when he was only seventeen he moved to Bermuda, where he was the lone teacher in a small educational outfit called the Whitney Institute. While he was there he kept up his interest in electricity, reading the technical magazines. He also met and married his wife Helen.

Determined to play some part in the new electrical industry, he left Bermuda for New York in 1885, and knocked on the door of Thomas Edison. He was turned down several times because of his lack of qualifications, but was eventually taken on to work on the laying of electricity cables, and later as a researcher at Edison’s Menlo Park.

Determined to play some part in the new electrical industry, he left Bermuda for New York in 1885, and knocked on the door of Thomas Edison. He was turned down several times because of his lack of qualifications, but was eventually taken on to work on the laying of electricity cables, and later as a researcher at Edison’s Menlo Park.

Most of Fessenden’s work was with chemistry rather than electricity, although the two were closely interconnected. He created a new form of insulating material, and in time became Edison’s most senior chemist. He might have gone on to work on Hertzian waves and wireless, but the burgeoning industry of electricity generation for lighting dominated Edison’s interest, and the new developments in electro-magnetism were put to one side. In 1890 Fessenden left Edison’s General Electric Company and over the next few years moved from one job to another, all the time adding to his inventions and building up his knowledge of electricity generation and its uses. This was an era when the patenting of new devices and inventions had become frenetic in the United States, and Fessenden had many to his name. He also spent some time in England, where he studied British developments and visited James Clerk Maxwell’s famous laboratory in Cambridge.

By 1892 Fessenden had a sufficient reputation to be offered the post of Professor of Electrical Engineering at Purdue University in Indiana. It was here that he began to experiment with Hertzian waves. After a year he moved on to Pittsburgh, where he was offered generous grants by Westinghouse, Edison’s great rival. When Roentgen’s discovery of X-rays was publicised in 1896 Fessenden, like many other scientists, took a great interest in them, and it was some time before he became intrigued by the possibilities of wireless. He claimed it was he who had suggested Marconi to the

New York Herald

as the man to cover the America’s Cup in 1899, turning down the job himself. In 1900, however, he accepted an offer from the US Weather Bureau which would enable him to set up a wireless research station, which was how he came to be on Cobb Island.

New York Herald

as the man to cover the America’s Cup in 1899, turning down the job himself. In 1900, however, he accepted an offer from the US Weather Bureau which would enable him to set up a wireless research station, which was how he came to be on Cobb Island.

Though Marconi enjoyed popular acclaim in America, US government departments were reluctant to deal with his company. Britain already dominated the world cable network, and there was a strong desire in America that the same thing should not happen with wireless. Both the Navy and the Weather Bureau wanted to encourage the development of home-grown talent, and Fessenden more or less fitted the bill, though he was Canadian. His task was to create a wireless system which would help the Weather Bureau track and forecast dramatic events such as hurricanes, and he was free to evolve whatever technology he liked, provided it was of some practical value. Marconi’s system of spark transmitters and coherer receivers would have done the job reasonably well, with a series of relay stations a hundred miles apart. His great achievement had been to show that wireless waves could travel at least that far, and there was no point in Fessenden repeating that experiment. There was, however, the potential problem of the infringement of Marconi’s patents which were being applied for in the United States. Fessenden recognised that, but it did not worry him much. He greatly admired Marconi for his youthful achievements, but felt that the spark- coherer system had done its job, and was in any case fatally flawed: it would never be able to send Morse signals at any great speed, and there was no prospect of it sending and receiving speech.

With scant concern for the expectations of his paymasters, Fessenden turned Cobb Island into something like a pure research station. He devised a new kind of receiver, in which a metal plate was immersed in liquid. This ‘barreter’, as he called it, was much more sensitive than the coherer, and could receive Morse at much greater speeds. Instead of the intermittent bursts of the spark transmitter, Fessenden wanted one which could generate something like a continuous wave of impulses. He did not care how far his signals would travel: he was intent on quality, not distance. Edison - who called him ‘Fessie’ - had told him that there was as much chance of transmitting speech as ‘jumping over the moon’. But in 1900, with a transmitter that sent out a high-speed stream of sparks and

his barreter, Fessenden did manage to send a spoken message to one of his assistants: ‘One, two, three, four, is it snowing there, Mr Thiessen? If it is, telegraph me back.’ The words were barely audible in the roar of static which the barreter picked up, but it was the first wireless telephone message ever sent.

his barreter, Fessenden did manage to send a spoken message to one of his assistants: ‘One, two, three, four, is it snowing there, Mr Thiessen? If it is, telegraph me back.’ The words were barely audible in the roar of static which the barreter picked up, but it was the first wireless telephone message ever sent.

Unfortunately for Fessenden, neither the US Weather Bureau nor anybody else showed the slightest interest in this achievement, and it was not widely publicised at the time. What possible use could there be for short-distance wireless telephony of such earsplittingly poor quality when there was already the telephone, and Morse for long-distance communication?

Marconi heard about Fessenden’s experiments towards the end of the summer of 1900, but they seemed to pose no immediate threat. Fessenden himself did not make any claims for his breakthrough, and continued to work for the Weather Bureau, which was sufficiently satisfied with his achievements in telegraphy to give him a new commission. He was to establish three new stations on the eastern seaboard, basing himself on Roanoke Island, North Carolina. This was where the first child of European settlers had been born in the sixteenth century, before the entire pioneer community had disappeared in mysterious circumstances.

Towards the end of 1900 the Cobb Island station was dismantled, loaded onto a schooner and shipped down to North Carolina. Two fifty-foot aerial masts were towed behind the ship, as they could not be loaded onto it. At the helm was the old sea-dog Captain Chiseltine, and among his passengers two of Fessenden’s young engineers. As they headed for Roanoke Island they hit rough seas. Fearing for the safety of his ship, the captain began to cut the tow ropes to the wireless masts free. He was restrained by the engineers, and luckily another ship came to the rescue. Fessenden’s equipment was saved, and his new station was set up in 1901.

Other books

Mystical Circles by S. C. Skillman

The Hundred and Ninety-Nine Steps by Michel Faber

The Templars' Last Days by David Scott

Girl Act by Shook, Kristina

Ladies' Man by Suzanne Brockmann

The Prodigal Girl by Grace Livingston Hill

Honeymoon from Hell IV by R.L. Mathewson

3 Ghosts of Our Fathers by Michael Richan

Wolf-Bound: Unfamiliar Territory by Rachel Bo