Simply Complexity (24 page)

Authors: Neil Johnson

They then tracked who is in a relationship with whom, how long the relationship lasts, and for how long these people are then single before meeting someone else. In other words, they were

able to measure

all

the things we might secretly want to know about relationships, but have been afraid to ask.

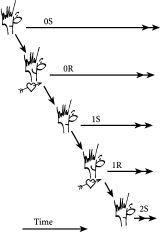

How long a given relationship lasts is determined by how closely the two preference lists coincide. The fact that relationships might then break up, and people may consequently have multiple consecutive relationships, means that every person’s romantic history can be condensed into a simple label such as “two previous relationships and currently single”. In other words, any person – male or female – can be labelled as follows:

0S if they have never been in a relationship and are currently single

0R if they are currently in their first relationship

1S if they have had one previous relationship and are currently single

1R if they have had one previous relationship and are currently in another one

2S if they have had two previous relationships and are currently single

and so on. Hence the label “NS” would mean that the person has had N previous relationships and is currently single, while “NR” means that they have had N previous relationships and are currently in a new one, the (N + 1)’th one. In short, anyone’s romantic life can be simply represented by a sequence of these labels, 0S 0R

0R 1S

1S 1R

1R 2S etc., stopping at whichever label describes their current state. Not only does this apply to the software men and women in the virtual dating simulation, but it also describes each one of us. It is strange to think of us as all that way, but it is true for real life as well. So next time you assess your love life, it may be somewhat sobering to see what your label is, following this scheme as sketched in

2S etc., stopping at whichever label describes their current state. Not only does this apply to the software men and women in the virtual dating simulation, but it also describes each one of us. It is strange to think of us as all that way, but it is true for real life as well. So next time you assess your love life, it may be somewhat sobering to see what your label is, following this scheme as sketched in

figure 8.1

.

What is interesting is the fact that this is also exactly how physicists label atoms which are going through successive stages of

radioactive decay. In particular, a radioactive atom starts off without having released any smaller pieces through decay. In other words, it is in state 0S. Then the atom starts decaying – in dating terms, it enters a relationship and hence is in state 0R. Then the atom stops decaying, and is hence described as the single state 1S and so on. In this way, Richard Ecob and David Smith were able to describe what happened to the people in their dating model using the language and mathematics of nuclear physics.

Figure 8.1

The ladder of love. We all start off with zero prior relationships, and single. Hence we start off as “0S”. This either lasts forever, or we enter into a relationship and hence change our label from 0S to 0R. If this relationship breaks up, we then have one prior relationship and are single again – in other words, we now have a label 1S. Then if we find a new relationship, we will be 1R and so on.

Using their simulation and this unlikely mathematics from nuclear physics, Richard and David were then able to build up an intuitive picture of how the ratio of singles to non-singles varies as the conditions change. In particular, they looked at the ratio of singles to non-singles in the long-time limit in order to understand what the eventual mix of the population would be. They could then use this ratio as a measure of how effective multiple-dating

actually is. In other words, they could see if the majority of the population eventually became paired off or not. Among the surprising things that they found was the fact that the sophistication of the men and women – in other words, the actual number of preferences in the list of personal preferences – has little effect on the singles-to-non-singles ratio in a large population. Suppose the criterion for forming a relationship is that at least half the preferences should be the same. Even if we double the number of items in the list, in other words the sophistication, a large population will always have a similar fraction of possible matches.

Hence Richard and David were able to show that in this relatively simple set-up it doesn’t really matter that we are all becoming more sophisticated by having ever longer lists of preferences. We can still find someone with whom we can form a relationship as long as the lengthening of our preference lists is not accompanied by an increase in our pickiness. In other words, if we tend to form a relationship with people who match at least half of our preference criteria, then lengthening or shortening everybody’s list has little effect on whether we will be single on average in the long run. So in this sense, the doom merchants who claim that increased sophistication will lead to a society with an increased number of single people have got it wrong.

By contrast, the average number of agents per site and the way in which these sites are connected together can play a very important role in determining the population’s dynamics. Increasing the average number of agents per site and/or the connectivity of the sites has the effect of making multiple dating more efficient. In a real-world context, this corresponds to increasing the rate at which we each meet other people on the network. This can either arise by you moving through the social network yourself or by sitting still and waiting for others to pass onto your social site. The key to the latter in terms of finding a good partner is to sit still at an important place – e.g. near a hub – on the social network.

Let’s talk through a particular set of their results, which can be thought of as applying to a set of people who start off dating for the first time as teenagers and then eventually pass through to mature adulthood. We start out with a completely random population of equal numbers of men and women, but with randomly

chosen preferences so as to mimic the diversity in a real population. Initially no one is in a relationship, nor have they had any previous relationships. Everyone therefore has the label 0S, and everyone is allowed to move around freely on the social network. Richard and David then allowed the relationships to start forming. The men and women start entering into relationships whose duration depends on how closely matched their preference lists are. Since most of the matches are not perfect, these pairs then start breaking up. Just as in real life, the variation in the length of relationships can be quite large. For example, it turned out that a few couples were indeed so well matched that their relationship lasted a very long time – but these really were the lucky few. The men and women coming out of this first relationship then took on label 1S, until they found someone else who would be suitable to date based on the similarity of the preference lists. And so the whole process went on with everyone heading down the road from 0S to 0R, to 1S etc. at different rates. How far they got down that road in the allotted time depended on whether they had been fortunate enough to come across people with sufficiently similar preferences. But on average, the whole population gradually moved along the same road – slowly but surely as time evolved.

In the long-time limit – in other words, as the teenagers moved though adulthood – the population eventually settled down to have a constant fraction who were in relationships, and some who

were single. But just as in real life, it was not always the same people who are single. The population wasn’t made up of spinster-types, and married-types. Instead, everybody had their moments of being in a relationship and their moments of being single.

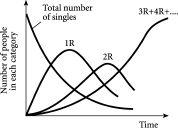

Figure 8.2

Socializing in the City. It turns out that if the number of people per site in the social network is large enough, such as in a lively city, then the number of people in a relationship will eventually tend to become larger than the number of singles.

Going further, they found that as long as the average number of people per site is sufficiently high – such as in a lively city with plenty of social life – then the practice of multiple consecutive relationships as in

figure 8.1

leads to more people being in a relationship at any one time than the number not in a relationship. These results are summarized in

figure 8.2

. The implications are that in a lively city repeated dating is a very good thing in that it leads to a population where there are more people in a relationship than single. Although there is intense competition for the right partner, a lively city effectively has a large supply of resources – in other words, a large supply of potential partners in easy-to-access places. Hence the population as a whole tends to do well if the individuals make pairs relatively frequently. By contrast, in a situation such as a rural setting where there is a low number of people per site in the social network, multiple dating actually leads to more people who are single at a given moment in time than in a relationship. This corresponds to the situation of a limited resource – hence the population as a whole does better by

not

making pairs too frequently. Interestingly, these two results for high and low levels of resource mimic what we had discussed in

chapter 5

in an entirely different context. There we found that for a competitive population with low resources, making connections was not beneficial. For the situation of high resources, by contrast, making some connections turned out to be beneficial for the population as a whole. So it is essentially the same result – but in a completely different context.