So Many Roads (37 page)

Authors: David Browne

The sessions also revealed the Dead's personalities and how they'd changedâor, in some cases, notâover a decade. Lesh was the chattiest and most technical, calling out chord changes and chord names. Kreutzmann wisecracked the most, and Weir remained the most relentlessly earnest, talking in his slightly halting way about local loggers versus the Sierra Club or the

Wide World of Sports

TV show. When he was at the sessions, Hart kept a low profile and didn't talk much, reflecting the ways he was slowly working his way back into the fold. “I just hung out,” Hart recalls. “I had a great feeling from everyone every day. You couldn't move in Bobby's tiny studio. It was really tight. But it felt the same. My relations with the guy was always the same. You didn't have to talk about these things.” (People like Parish and Swanson felt that Hart seemed to be more tentative at this point, careful not to overassert himself as a way of mending fences and re-insinuating himself into the Dead.) A far more mysterious and fleeting presence was Keith Godchaux.

When Garcia spoke, everyone else would quiet down and listen. Even if he was just discussing a Don Reno and Chubby Weiss bluegrass show he'd attended, Garcia remained the unquestioned center of attention. He mentioned that the band had received an offer to play in the Middle East. Just a few weeks later, on March 25, Faisal would be assassinated, and the resulting album,

Blues for Allah

, would be named in his honor.

They needed a rock 'n' roll tune, and late one evening Garcia volunteered, reminding everyone that “Loose Lucy,” the slinky rocker off

From the Mars Hotel

, had taken him all of twenty minutes to write. But conventional rock 'n' roll, even in the Dead's loose definition of that phrase, wasn't what anyone had in mind as the days and weeks at Ace's

gradually unfolded. Garcia wanted the band to sound fresh, to blow away all the musical and financial headaches of the last few years, and the solution was having

no

new material at allâto come up with it on the spot. A song might start with Lesh strumming chords on an acoustic guitar (or humming the melody to what would eventually transform into a song, “Equinox,” that the band wouldn't attempt to record until their next album). It might launch with Lesh, Weir, and Garcia all playing simultaneously, sometimes for hours, trying to find the right new tone or direction.

Or, as it did on the night of February 26, it might start with Garcia playing a few, well-chosen guitar chords. When they found something, Hunter would show up and write lyrics along with the music, an atypical approach even for him. “It was comfortable being in Weir's house,” says Candelario. “That was generally the mood in those days. They got along with each other. It was fun to hang out. Making records wasn't one of their professions, but that album was totally different.” The less stressful atmosphere would be easily heard in the more relaxed, elastic song structures and rhythms in songs like “Help on the Way/Slipknot!” (which Lesh would later call “one of our finest exploratory vehicles”), the reggae sway of “Crazy Fingers,” and the breezy “Franklin's Tower,” partly inspired by the “doo-da-doo” chorus on Lou Reed's “Walk on the Wild Side.”

As the weeks at Weir's studio continued, it became obvious that their enforced hiatus wasn't about taking a break from each other as much as it was from the overwhelming industry of the Dead. Even when the band was frittering away time, the experience at Weir's studio reinforced that music could still be their bond. Despite all the personal and business headaches swirling around the band, they could still come together in a small space, pick up their instruments, and continue the sonic journey they'd begun a decade before. In a heartbeat or something close to it, they could return to those days at Dana Morgan's

music studio in Palo Alto, or the Acid Test nights, or the long days ensconced in professional studios creating

Aoxomoxoa

or

Anthem of the Sun

. And even better, they could still

enjoy

it.

Late the night of March 5, after almost a month of tossing around ideas and trying to invent a new sound, they began hitting on that mysterious, intangible new approach. Garcia suggested playing in unison, either a chord or just a note. The others guffawed or chuckled, as if in disbelief, but he continued: how about holding one note for two bars, then having two of the players shift to the third bar? The idea was to all play octaves simultaneously and musically hop around each other. It was an audacious thought, and they decided to go for it.

To demonstrate, Garcia played an F on his electric guitar; Weir and Lesh followed suit with the same chord, and finally Kreutzmann joined in. The result was a mammoth drone, a Wall of Sound in the studio, and everyone was palpably excited by it. They kept working on a pieceâwhat would eventually come to be known as “Unusual Occurrences in the Desert”âand Garcia was thrilled, telling them he felt like he wanted to keep playing it forever. Even when the band would stop playing, Garcia rarely would; his guitar, that ambrosial sweet sound, would continue reverberating around the walls of the studio.

When would they complete the material, and when would they perform any of it live and work it up onstage? Those questions were still unanswered. As it was, they'd already committed to one show, a Bill Grahamâorganized benefit for SNACK (Students Need Athletics, Culture, and Kicks, a nonprofit founded by Graham) at Kezar Stadium. “Even though the band wasn't playing and everybody needed some breathing room, there was a large sense of family that never went away,” says Debbie Gold, then working in the Garcia office with Loren. “They were around each other, and there were family events. It was a small community of people, but everybody needed some breathing room. Bill [Graham] willed that to happen. He said, âI want the

Dead to play.' He was so passionate and determined and would not take no for an answer.”

The Dead had agreed to participate, but not without chewing it over at Weir's studio. Weir wondered whether they would have time for a soundcheck before they went on, and Garcia assured him the pressure would be off given that the other scheduled acts included Bob Dylan, Santana, Neil Young, and Jefferson Starship. Plus, Garcia added, they'd only have to play an hour. The band cracked up. At last they could laugh about something, and more important, they could laugh about it together.

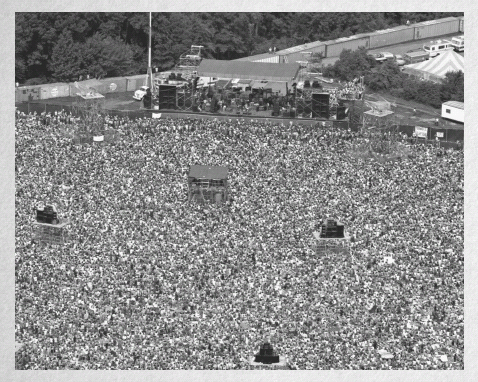

The new era, arising: The vast crowd and empty boxcars at Englishtown.

PHOTO: HARRY HAMBURG/NY

DAILY NEWS

/GETTY IMAGES

ENGLISHTOWN, NEW JERSEY, SEPTEMBER 3, 1977

As their helicopter whirly-birded toward the grounds, Garcia, wearing one of his customary black T-shirts, and Richard Loren, their manager of nearly three years, weren't sure what to expect. No one was. Along with John Scher, the gregarious, Jersey-based promoter who had started booking their east-of-the-Mississippi shows, both men knew that the corridor between Washington, DC, and Boston had been teeming with Deadheads. In 1970 alone the band played seemingly nonstop in the New York area and built up one of their most rabid followings.

But today's concert in Englishtown would nonetheless be a test and a gamble. The nearby raceway, its name immediately recognizable to anyone who'd grown up in Jersey and heard its ubiquitous “RRRRaceway . . .

Park!

” radio ads, could hold up to ninety thousand people. Aside from their participation in festivals, the Dead rarely if ever played to that many paying customers, and no one was 100 percent sure whether that many

would

pay. The weather was another miserable

factor: by the time all the members of the Dead began arriving in Englishtown the Jersey Shore's notoriously humid summer heat had blanketed Raceway Park.

The tickets had begun selling briskly, a positive sign for the Dead but bad news for local municipalities, who were horrified at the thought of tens of thousands of unruly rock fans descending upon their suburbs. Scher told authorities he'd be lucky to sell fifty thousand tickets, but that didn't mollify the politicians. “We were still in an era,” he says, “where anything that smelled, hinted, or suggested Woodstock scared people.” The towns sued to shut down the concert; when that failed, mysterious construction jobs on all the major roads leading to Englishtown suddenly materialized a day or two before the concert. Luckily for Scher, a judge ordered the towns to fill in the holes they'd already dug in the highways.

Not every Deadhead heard about the ruling, and starting the night before the show, many simply ditched their cars as close to Raceway Park as they could and began walking. To prevent gate-crashing, Scher devised a complicated but ingenious security planârenting empty boxcars from local rail yards in Newark and connecting them in a large circle around the park. (The Dead's crew jokingly referred to the sight as the “Polish Railroad”â“it looked like a train, but didn't go anywhere,” chuckles a friend who was there.) Fans couldn't squeeze in between the cars, nor could they climb up its slippery surfaces; if they did, they'd be greeted by security guards patrolling atop the boxcars. One fan managed to slip in, holding massive wire cutters, and was stunned to discover there was no fence to slice open even if he wanted to do it. Working to set up the stage throughout the day, Steve Parish and other members of the crew took in the spectacle. “From the side of the stage we watched the security guards repelling people all day long who were climbing up those things,” Parish says. “It was just bursting at the seams.”

But nothingânot highway snafus nor the oppressive summer weather that would normally drive East Coasters indoorsâwas keeping the cult away. As their helicopter made its way over Raceway Park, all Garcia and Loren saw was an enormous, swirling mass of bodies extending as far as they could see. “Oh, my God!” Loren said, turning to Garcia. “What a fan base we've got!”

At was his custom, Scher walked out onto the stageâwith its massive Cyclops-with-a-skull backdropâas the band was about to go on and introduced them, one by one. The Dead didn't ask him to do that, but Scher did it anyway, in part because he assumed most of the fans probably didn't know anyone's name other than Garcia's. Then he walked off, they started up “Promised Land,” and the time came to see what would happen when the Dead tried to hold the attention of close to one hundred thousand people on the other side of the country from home.