So Many Roads (41 page)

Authors: David Browne

After the encore, an eleven-minute run-through of “Terrapin Station Part 1,” they couldn't wait to return to their air-conditioned Manhattan hotel rooms. But everyone came away with one clear lesson: they could dismantle the band for a while. They could return, as they had the year before, without a new studio album to promote. They could make an album that would leave the fans ambivalent. They could force their fans to walk miles in the heat and then wait hours in the body-fluid-depleting sun to see them play. And when they did perform, as at Raceway Park, they could do it with two of their members physically incapacitated, hampering the music along the way.

Onstage and off, they could screw up as much as they wanted, yet none of it seemed to matter. The fans still adored them and would cut them enormous amounts of slack merely for the opportunity to see them play. The experience, the gathering, was as much the point as the performance. Just after Raceway Park Arista ran an ad in

Rolling Stone

with photos from the show and the copy, “A New Dead Era Is Upon Us.” Even if they didn't realize it at the time, the era arrived with many new lessons.

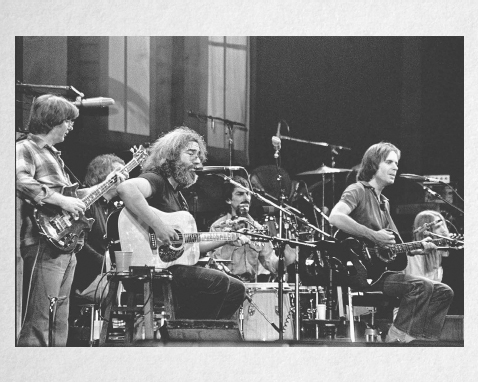

Unplugged at Radio City Music Hall in New York, with Brent Mydland, far right.

© BOB MINKIN

NEW YORK CITY, OCTOBER 31, 1980

Even the union workers agreed: part of the wall had to go. After all, the Dead had a slew of shows about to begin, and their damn recording consoles had to be installed. If it meant a portion of a stairwell had to be removedâin a building that had just been given landmark status by the city of New Yorkâso be it. On the occasion of the Dead's fifteenth anniversary, nothing and no one could stand in their way, not even Radio City Music Hall.

Just over a week before, the load-in had begun for the Dead's eight-night stand at the six-thousand-seat venue. On many levels the sight would have been unimaginable several years before. The venerable midtown building had opened its doors nearly fifty years before, in 1932, and by 1980 any tourist who came through the city seemed to be legally required to attend Radio City Music Hall's Christmas and Easter shows with the Rockettes or see one of the family-themed movies it hosted. But by the late seventies, with New York City in fiscal freefall, Radio City's future was suddenly shaky; movie attendance dropped, and plans to convert it into an office building or parking lot loomed.

Thankfully the interior of the building was granted landmark status in 1978, and its famed art-deco lobby and other interior design elements were refreshed for $5 million. During talks to save the building the idea of booking pop acts came up, and by the fall of 1980 Radio City Music Hall had presented one major pop star, Linda Ronstadt. Now it would host an entirely different kind of beast, the Grateful Dead, who were about to settle in for eight nights, October 22 to 31 (with the nights of October 24 and 28 off).

The band's clout became evident right away, when Deadheads converged upon Rockefeller Center, some camping out, and snapped up almost thirty-six thousand tickets priced between $12.50 and $15.00. In an ambitious move that recalled the special screenings of

The Grateful Dead Movie

, the last night, Halloween, would be broadcast live by a closed-circuit feed to fourteen movie theaters around the country; in addition, all the anniversary shows, both at Radio City and preceding ones at the Warfield in San Francisco, would be recorded for a live album or two. The entire undertaking felt like an event, especially when word trickled out that the band would be playing its first acoustic set in a decade, complete with their fairly new keyboard player.

To accommodate the recording the Dead needed two hefty Neve recording consoles, one rented and the other shipped out from their Front Street home base. Both had to be hauled up a flight of stairs to reach Plaza Sound, the studio that sat atop Radio City (and where punk bands like Blondie and the Ramones had recorded). The Dead's office had sent paperwork ahead of time to make sure the consoles would be able to make it into the building, but when the time came to install them, a problem arose: the consoles couldn't quite clear the stairwell. After some head-scratching, one of the union workers at the venue, with Hart's urging, said, “Oh, fuck itâwe've gotta get this thing up here.” With that they grabbed a sledgehammer and took down a few inches of the stairwell wall.

Promoter John Scher had no idea the “renovation” was happening until he heard from Betty Cantor, who would be recording the shows, and the thought of physical damage to the interior of a New York landmark rattled even Scher, who thought he'd seen it all with the Dead. “I remember Betty telling me after they'd already done it, after the fact,” Scher says. “I was basically shitting in my pants until the shows were over.” It wouldn't be the first time the Dead would encounter some pushback in their career, but this victory was significant. “I had no second thoughts about that,” says Hart. “It was the thing to do. Nothing stops the Grateful Dead. Onward into the fog.” They'd already made it to fifteen years despite adversity, busts, deaths, and fallow periods, and no one was about to let a bit of concrete stand in their way.

By then the bright memories of 1977 were starting to dim. Beginning the following year, the self-control and efficiency that had marked the previous year was beginning to slip out of the Dead's grasp, and the grind of touring was starting to wear them down. “When I first came along people were doing a little bit of everything,” says Courtenay Pollock, the tie-dye artist now fully immersed in the Dead world on and off the road. “But with the demands of these tours, people started jacking themselves to keep up the pace.”

Culturally the Dead were also now out of sorts. Thanks to the rise of punk rock and disco, the Dead, although only in their thirties, were now ensnared in what amounted to a sixties backlash; anything that even vaguely reeked of patchouli oil and weed was newly reviled or mocked. Even the country's hip, Dylan-quoting president, Jimmy Carterâwho'd been elected in 1976, the same year the Dead returned to the roadâwas beginning to stumble. In the next election, a month after the Radio City Music Hall shows would wrap up, the country would embrace Ronald Reagan, a symbolic gesture of political and cultural change.

Eager to simplify themselvesâand rejecting a return to the buffed sonics of

Terrapin Station

âthe Dead hired Lowell George of Little Feat to produce their next album. The hookup sounded ideal: George had his feet planted firmly in American roots music, and the band could relate to him (and his funky, cutting-razor slide guitar) more than they could Keith Olsen. For extra comfort, the sessions wouldn't be held in Los Angeles but at Front Street, the Dead's warehouse in San Rafael. Although the band had been renting it for a few years, Garcia had used Front Street the previous year to record his Jerry Garcia Band (or JGB) album

Cats Under the Stars

. Maria Muldaur, the sexy-voiced former jug-band singer who'd had a hit with “Midnight at the Oasis” in 1974, sang on several tracks on the album, thanks to her relationship with John Kahn, Garcia's buddy and favorite non-Dead bass player. “Jerry and John were like spiritual brothers,” says Muldaur. “It was musical, and it was something beyond that. Jerry respected John and the knowledge he had of other kinds of music. He liked his sensibility. They had this intuitive connection.”

Kahn and Muldaur had been a couple since 1974, and now, years later, Muldaur was witnessing the craziness at Front Street for herself: recording sessions that started after midnight and were fueled by coke and wine. (Because she had a young daughter and woke up early each day, Muldaur took to carting along an espresso machine to help keep her awake late at night: “I called it Italian cocaine.”) Yet Garcia's side band, which had started in 1975 during the Dead's hiatus and was now more or less known as the Jerry Garcia Band, was by now a legitimate and flourishing concern. With players that included Kahn, Elvis drummer Ron Tutt, and Keith and Donna Godchaux, with others to follow, the JGB allowed Garcia to revel in different rhythms and repertoire than the Dead. (

Don't Let Go

, a live album recorded in 1976 but released much later, was a prime example of the group's loose, funky Marin swing.) The sessions at Front Street for what would be Garcia's fourth

studio solo album were especially productive. From Garcia's biting guitar on the pumped “Rhapsody in Red” to the enchanting story-song “Rubin and Cherise,” about a love triangle set in New Orleans, the album featured some of Garcia's best outside-Dead work, and he would be justly proud of it for years after. Its lack of commercial success would also be devastating to him.

Months later at the same place, work on the Dead's new album,

Shakedown Street

, would prove far less satisfying. It was George's idea to tape the band at their rehearsal space, and with him they finally recorded “Good Lovin',” one of Pigpen's showcases, now with Weir singing lead. George did return the band to its dance-band roots with a modern twist; the title song leapt into a disco pool even more so than their cover of “Dancin' in the Streets” on

Terrapin Station

, and Weir and Barlow's “I Need a Miracle” roared in ways the Dead hadn't done in the studio before. With his white overalls, genial manner, and love of American music, George was seemingly a natural match for them. But the material was patchy, and the party atmosphere at Club Front wasn't helping; George was no stranger to cocaine, and he and some of the band members (and crew) indulged themselves regularly. “A lovely guy, but he was screaming on coke the whole time,” says Hart. “He was killing himself. And, again, it was a desperation move. Nobody in their right mind would want to be the producer of the Grateful Dead. It's a death sentence. No one can handle that. They always crack up.”

After school Justin Kreutzmann would show up to watch his dad work and, he says, “Everyone would still be up from the night before. Everyone was so unhealthy and the combination of Lowell and the Dead wasn't doing anyone any good.” Weir invited his old friend and former Kingfish partner Matthew Kelly to play harmonica on “I Need a Miracle”; when Kelly showed up, George immediately lectured him. “Lowell came up to me and said, âI don't allow any drugs at my

recording sessions,'” says Kelly. “Which was ironic and somewhat hypocritical. Everyone was using them.”

In the midst of that work one of their grandest adventures was taking shape. Thanks largely to their manager and booker, Richard Loren, they would be heading for Egypt for three nights of concerts in September 1978. The trip involved all manner of paperwork and diplomatic massaging, including trips by Loren, Lesh, and Alan Trist (now a longtime band employee) to Egypt and Washington, DC. Eventually they arranged it so the trip would be a fundraiser for two Egyptian charities (as opposed to a State Departmentâsanctioned trip that might raise eyebrows), and their dream of playing their most celestial music at the foot of the Pyramids became a reality.