Sons (41 page)

Authors: Evan Hunter

You could buy pot on any street corner in Saigon; the stuff grew wild in the countryside and even the school kids were selling it for five dollars a bag. This wasn’t the same nickel bag you got back home, though; here it contained about two ounces of the stuff, enough for maybe ten or twelve cigarettes. In a bar on Tu Do Street, Pete and I bought a bag from a girl who kept insisting she’d be fired if her boss knew she was peddling grass on the side. We told her we wouldn’t tell him if she didn’t, and then bought her another glass of Saigon tea for a hundred and fifty pee, which seemed to mollify her for a little while at least. There was a jukebox going in the bar, stacked with records that were a month or two behind what was being played in the States, all rock, country-western, and blues, old hits like The Dave Clark Five’s “Over and Over” and Herman’s Hermits’ “A Must to Avoid.” The bar was crowded with young guys in civilian clothes, most or all of them serviceman, I guessed — Negroes, whites, a few Koreans. (

Pete

told me they were Koreans; I thought they were Vietnamese.) A Negro standing alongside of us was very proud of the United States Army jungle boots he had bought in the black market on Le Loi Street, and kept showing them off the way a newly engaged girl shows off her diamond. They had cost him ten thousand pee, about eighty-five American dollars, but he was expecting to be transferred out to the boonies any day now, and he had heard of guys waiting six to eight weeks to get boots issued while meanwhile they were walking around in the paddies all day and getting seven kinds of jungle rot. It had been a hell of a lot easier to buy them on Le Loi Street, the Negro said, and then asked Pete and me if we thought he’d made a mistake. The girl draped on his shoulder said, “You no makee mistake, Lloyd, them Number One boots.”

Pete

told me they were Koreans; I thought they were Vietnamese.) A Negro standing alongside of us was very proud of the United States Army jungle boots he had bought in the black market on Le Loi Street, and kept showing them off the way a newly engaged girl shows off her diamond. They had cost him ten thousand pee, about eighty-five American dollars, but he was expecting to be transferred out to the boonies any day now, and he had heard of guys waiting six to eight weeks to get boots issued while meanwhile they were walking around in the paddies all day and getting seven kinds of jungle rot. It had been a hell of a lot easier to buy them on Le Loi Street, the Negro said, and then asked Pete and me if we thought he’d made a mistake. The girl draped on his shoulder said, “You no makee mistake, Lloyd, them Number One boots.”

“You think so, Annie?” Lloyd said.

“You jus’ lookee them line boots,” Annie said. “Hey, mistah, you tell Lloyd here them Number One boots.”

“Those are sure Number One boots,” I said.

The girl who’d sold us the grass came over just then and said, “Hey, Cheap Charlie, alia girls

soooo

thirsty, you wanna talk some?”

soooo

thirsty, you wanna talk some?”

“He wants to

fuck

some,” Lloyd said, and Annie burst into tinkling laughter and buried her face in her hands.

fuck

some,” Lloyd said, and Annie burst into tinkling laughter and buried her face in her hands.

“No talkee fuck,” the grass-girl said. “Alla girls

soooo

thirsty here, my goo’ness, le’s drink some nice tea, okay?”

soooo

thirsty here, my goo’ness, le’s drink some nice tea, okay?”

“It’s getting awful,” Pete said. “You used to be able to go into any Saigon bar and work your points with these girls for the price of, oh, three, four glasses of tea — but then the tea only cost about eighty pee. What you were doing, you know, was trying to get yourself a steady shack, buying for the same girl every time you came in, hoping you could get to take her home one night. There’s an eleven o’clock curfew here, Wat, so most of these joints close around ten-thirty, quarter to eleven, and if you’re lucky and you get to take one of them home, why you can maybe get something good going, you know? You can rent places for these girls for about thirty bucks a month, and then all you got to do is, you know, bring home the usual crap, some C-rations every now and then, cigarettes, fans, goodies from the PX, and that way you got yourself a great thing going, a relationship, you know? I mean, you can always get laid in Saigon, there’s a hundred short-timers working this street, they’ll give you a quick one on a mattress out back for three or four hundred pee, but what a man needs is a

relationship,

Wat, that’s what he needs.”

relationship,

Wat, that’s what he needs.”

“Hey, what you say, Cheap Charlie?” the grass-girl said.

“Fuck off, sister,” Pete answered. “We’re busy talking, can’t you see?”

The Buddhists came into the streets as flares filled the nighttime sky over the city. They had rallied outside Saigon’s brightly lighted Buddhist Institute, the Vien Hoa Dao, and now they marched in flowing white robes, followed by shouting citizens carrying hand-lettered banners and the saffron, red-striped flags of South Vietnam. There had been unrest in the streets ever since President Johnson’s February meeting with Premier Ky in Honolulu, at which time it had seemed to the Vietnamese that our wily Senate cloakroom negotiator had tucked their man into his vest pocket. But three days ago, on March 10, Ky had dismissed a Buddhist-supported general from his ten-man military Directory, and now the priests were out in force to demand the overthrow of his government. Riot policemen in Army fatigues and helmets flanked the route of march, expecting trouble, expecting perhaps the same kind of big trouble they had known on June 11, 1963. On that day, at the intersection of Le Van Duyet and Phan Ding Phung Streets, at nine o’clock in the morning, the Venerable Thich Quang Duc, a member of the Buddhist clergy, had set fire to himself, thereby giving undeniably visual form to the flaring anger of the priests, who claimed that the Catholic President Ngo Dinh Diem was discriminating against the country’s sizable number of Buddhists, variously estimated as between fifty and seventy per cent of the population. Being an American raised in the Judaeo-Christian tradition (as it was euphemistically called, forgetting for the moment the centuries of strife behind that handy twentieth-century label) I had no idea what a Buddhist believed. There had once been a Buddha, true; very good, Wat Tyler. There had also once been a Confucius, and his teachings formed the basis of yet another Vietnamese religion. But it was there that beliefs such as Cao Dai, and Hoa Hao, and Taoism entered the picture and caused a Westerner like myself to become hopelessly mired in a culture as deep and as resistant as the muddy rice paddies through which we pursued our war, a culture that surely included the throngs of Buddhists and their followers who demonstrated in the streets now against the very government we were supporting.

A Mercedes-Benz convertible, ten thousand dollars on the hoof, was being rolled over, and someone ran up to it with a flaming torch, right arm back, wrist slightly bent, left arm out for balance like a tennis player coming in to return a powerful serve, swinging the firebrand in a wide arc and then releasing it and allowing it to sail through the open window of the overturned car. The convertible top caught, there was an expectant hush as the crowd awaited the inevitable, and then pulled back and ducked and ran as the explosion came and flames billowed up toward the sky. The riot policemen charged into the group of demonstrators, gas masks pulled down over their faces, wicker shields hooked over their arms and thrust forward to deflect the stones and tin cans being hurled at them. There was a hiss, a puff, a cloud of tear gas erupted in the middle of the street, and the crowd screamed, barefoot school children wearing shorts and white shirts, older youths in Army trousers and American sneakers, plastic bags appearing here and there among the crowd, pulled over heads in defense against the gas, had no one ever told these people about the Great American Plastic Bag Scare? There were television cameramen shooting footage for news programs to precede “The Tonight Show starring Johnny Carson,” another explosion as a motorbike burst into flame. And then a slender Buddhist monk, pate shaved, raised his white-robed arms and strode on floating sandals into the crowd of dispersing followers while behind him a riot policeman approached with upraised club. “Behind you!” I shouted, and Pete grabbed my arm and said, “For Christ’s sake, Wat, keep out of it! This is gook business!” The club fell, a bright red gash appeared across the top of the priest’s head. He dropped to the sidewalk running blood, his white robe glowing eerily in the light of the flames from the motorbike nearby.

I had told my father during our unsuccessful Judge Hardy chat in the living room of our house last November that I was going to appeal my classification and ask to enter the Army as a noncombatant, but that was before I knew what was actually involved. I had thought it was merely a matter of running over to my local draft board the next day, showing them my classification notice, and saying, “I know I’m classified 1-A, but I’d like to change that now if it’s ail right with you. I’d like to be put in 1-A-O, which as you know means I object to taking up arms against an enemy, but I don’t object to military service in a noncombatant status. So will you please make the necessary changes?”

“You mean you want to appeal your classification?”

“Yes, I’d like it changed to 1-A-O.”

“You’re asking for an exemption.”

“I’m asking for reclassification.”

“You’re appealing your present classification and asking for an exemption.”

“Okay, yes.”

“Fill out this form. Mail it back to us within ten days.”

“All I’m asking...”

“There are no automatic deferments or exemptions. Fill out this form. The Selective Service will decide whether to accept or reject your appeal.”

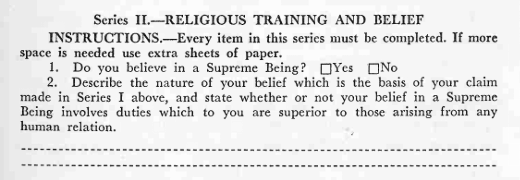

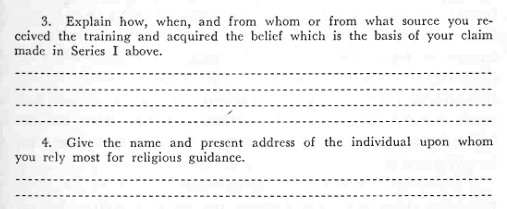

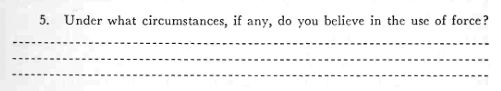

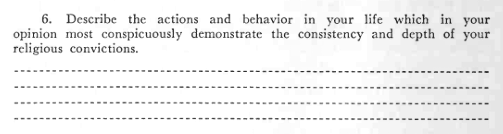

It occurred to me, as I looked over the form for the first time, that it would have made an excellent mid-term examination for a graduate student in theology. I visualized a bare-assed southern Baptist, dunked into a river at infancy and subsequently raised as a God-fearing citizen, trying to cope with the complexity of language in the form, and finally throwing up his hands in despair — fuck it, I’d druther go fight. My own situation was not too dissimilar. To begin with, I knew beforehand that a Supreme Court decision in March 1965 had broadened the legal interpretation of the first question in Series II. RELIGIOUS TRAINING AND BELIEF, so that belief in a supreme being did not necessarily have to mean belief in God, but could instead mean “belief in and devotion to goodness and virtue for their own sakes, and a religious faith in a purely ethical creed.” I knew all about the Seeger case, and I knew about the decision, and I was therefore surprised to discover, as late as November 30 of that year, that the question “Do you believe in a Supreme Being?” was still on the form. I recognized, of course, that I could answer “No” to the question if I so chose, supposedly without prejudicing my appeal, but I was honestly unprepared for the emphasis on religion throughout the remainder of the form. I was not a religious person. Oh yes, I had been in and out of the First Congregational Church every Christmas Eve as part of the ritual of singing carols around the enormous firehouse tree, and then going over for midnight mass, and I had also been there for services on the day after President Kennedy got shot, but I could not be considered a “churchgoer” in any sense of the word, nor had there been any really strong religious influences in our home (though my mother did try to get me interested in Ethical Culture and took me to a meeting in Stamford one Sunday morning). My objections to the war in Vietnam were purely moral, and it seemed to me unfair that I was now being asked to justify those beliefs by pretending they were religious — in other words, by lying.

Other books

World of Suzie Wong : A Novel (9781101572399) by Mason, Richard

Red Bird's Song by Beth Trissel

The Bite That Binds (The Deep In Your Veins #2) by Wright, Suzanne

Calling the Play by Samantha Kane

Bumped by Megan McCafferty

Sadie Whyte: The Lust of my Life by HD HOTEP

Foreign Faction: Who Really Kidnapped JonBenet? by Kolar, A. James

Mail Order Rose (Mail Order Brides #1) by Cabot, Cara

Monte Cassino by Sven Hassel

Cyberella: Preyfinders Universe by Cari Silverwood