Southern Storm (28 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

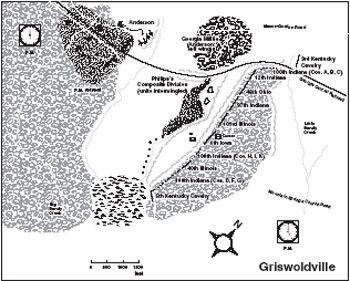

From his position along the tree line, Brigadier General Philips watched his center units advancing “in fine style under a heavy and galling fire.” The two local defense battalions on the right flank, which were slow getting started, lagged behind the State Line troops, who were moving apace with a militia brigade on their left. A shallow gully was encountered where the Confederate line steadied to deliver a volley at the

distant foe. Then the advance resumed, the lashing of bullets coming from the enemy position showing no diminution.

After what seemed an eternity, the first line reached a large gully carrying one of the branches

*

feeding Big Sandy Creek. This deeper trench offered protection from the lead hail spitting in their faces, and for many participants this would be their high-water mark. The advance did force the enemy skirmishers to abandon their forward posts in the farmhouse ruins and scamper into the main position. Within minutes, the second and third lines had pushed into the first, jostling for cover among the gall bushes, scrub pines, and reed cane. Also coming forward was the reserve militia brigade, which was so confused and rattled by the inferno that its first volley was loosed into the backs of some of the Georgia State Line.

A Yankee soldier standing in the ranks of the 103rd Illinois later termed this encounter “quite a hard fight.” The enemy infantry, recalled a member of the 97th Indiana, “came at us with force and fury,” while a comrade in the nearby 100th Indiana wrote that the Georgians “charged us and fought furiously.” “We kept on loading and firing till the smoke got so thick it almost blinded us,” added another Hoosier, “and our guns got so hot they burned our hands.”

Soon after sliding into the deep gully wriggling roughly parallel to the Federal line (at distances varying from 45 to 100 yards), determined Confederate officers began concentrating on overwhelming the Union right flank. To meet this threat, Brigadier General Walcutt started thinning his left to reinforce his right. He shifted the 46th Ohio from one end of his line to the other, and made two calls on the 100th Indiana—one for three companies to plug the gap created by the withdrawal of Arndt’s cannon, and the other to screen the extreme right. Because of these moves, three Hoosier companies had to now cover the frontage previously held by one and two-thirds regiments, but fortunately most Rebel effort seemed directed against Walcutt’s right.

Even though Anderson’s gunners were operating virtually unopposed,

the proximity of the Georgians to the Yankee line forced the artillerymen to choose their targets with care. The abandoned Duncan farmhouse was an obvious mark, with the added bonus of its being Brigadier General Walcutt’s headquarters. One of Anderson’s well-placed rounds exploded near the brigadier, driving a shell shard into the lower part of his right calf, causing a painful and incapacitating wound. The officer was carried off to the field hospital in the rear, near Mountain Springs Church. Command devolved to the senior regimental commander, Colonel Robert F. Catterson of the 97th Indiana.

Making a quick assessment of the situation, Catterson was not happy with what he found. Several units were reporting low stocks of ammunition, and the enemy was continuing to press him hard on the right. “As I had already disposed of every available man in the brigade, and my [thinned] left being so strongly pressed that not a man could be spared from it, I sent to the general commanding the division for two regiments.”

Incredibly, the Confederate militia, local defense, and State Line soldiers maintained their position in the forward gully for nearly two hours. “The firing was incessant,” reported the State Line commander. A man in his ranks remembered that “the boys fell one after another.” When the man was himself hit, he made himself small behind a tree stump while enemy “bullets…cut the ground on either side.”

For his part, Brigadier General Philips lost all control of events once contact was made and remained at the tree line. An effort to get Major Cook’s local defense battalions to flank the enemy’s left “(from some cause of which I am not aware)…was never carried out,” Philips complained afterward. Also, without any order from him, the militia brigade standing in reserve advanced into the field to join the others in the far gully.

From the few extant reports and accounts of this action, Philips played no role once the engagement was under way. Perhaps overwhelmed by the spectacle of what he had initiated but was unable to manage, the militia officer became a spectator. There would be rumors afterward (but no actual accusation) of alcohol abuse, but this is often a ready excuse to explain errors of judgment. No charges of drunken

ness against Brigadier General Pleasant J. Philips are found in any contemporary account from knowledgeable sources.

Of the men filling that broad gully, only bits and pieces of a picture emerge. That there was confusion is attested to by at least one report. Someone must have maintained a firing line near the gully lip to discourage any enemy forays against the position, although Federal sources indicate that their aim was poor, with most shots passing harmlessly overhead. Other officers rallied units together time and again in an effort to drive the invaders away. According to some accounts, at least three and perhaps as many as seven separate assaults lurched out of the gully, only to be beaten down by the torrent of gunfire. The last took place near the end of the engagement, when the left wing of Brigadier General Charles D. Anderson’s brigade, which had gotten separated from the other wing, tried to turn the Federal right flank.

By the time of the battle’s close, no less than three of the unit commanders—Brigadier General Anderson and colonels James N. Mann

and Beverly D. Evans—had been hit. What kept the Georgians trying for so long had little to do with strategy or even tactics. In a telling comment from the battle’s aftermath, a mortally wounded militiaman told his captors: “My neighborhood is ruined, these people are all my neighbors.”

The Union soldiers were confident but not cocky. “I never saw our boys fight better than they did then,” declared a member of the 100th Indiana. “Once when we were so hard pressed that it seemed as though they were going to run over us by sheer force of numbers our boys put on their bayonets resolved to hold their ground at any cost.” “At one time it seemed that they would overcome our thin line, as our ammunition [was] nearly exhausted and none was nearer than two miles,” reported the commander of the 103rd Illinois, “but fortunately a sufficient amount was procured, and our boys kept up a continual fire.”

It was growing dark before the reinforcement Catterson had requested reached the scene of the action. There were three regiments: two cavalry and one infantry. A mounted unit was sent to the left, the others further bolstering the right. Also back was Major General Osterhaus, whose meeting in Gordon with Major General Howard had been interrupted by “a rather severe cannonade in the direction of Griswold[ville].” Osterhaus arrived “soon enough to witness the last efforts and entire rout of the enemy.”

There was nothing dramatic about the end of the battle. It was almost as if the men and officers on both sides decided that enough was enough. Some of the militiamen called it quits on their own. Private William Bedford Langford recollected heading across the clearing in the rear toward the woods with a friend. “Just about half way across,” he often told his daughters, Yankees began firing at them, about twenty or twenty-five bullets hitting around them, but neither of them was shot. He said neither he nor his companion ran until they reached the woods and then “they surely did run.”

Most withdrew under positive commands to do so. One of the Confederate officers in the gully wrote that night came “and, ammunition being well-nigh exhausted, the commands retired in good order.” That

latter description was repeated in all the Southern after-action reports, suggesting a weary but unpanicked withdrawal, though not without some bitter recrimination from the ranks. A militiaman complained in a letter home of their “leaving some of our killed and wounded on the field exposed to the severities of a very cold night.”

Brigadier General Philips claimed his intention was to halt in Griswoldville so he could send out detachments to haul in the wounded, but orders were waiting there for him to return his command to Macon. Thanks to some aggressive track repair, the bone-tired soldiers had to march only two and a half miles from Griswoldville to where trains—and medical assistance—were waiting.

The men began arriving back in Macon at 2:00

A.M

., to streets that were as dark and empty as when they had departed. For the citizen-soldiers who had fought with determination but without success, it was a very long and very terrible day.

The volume of fire coming from the Rebel-held gully diminished noticeably after sunset, soon petering out altogether. Federal officers huddled, and at the sound of a bugle, skirmishers from at least four regiments nosed cautiously forward. “The scenes of death, pain, and desolation seen on the field will never be erased from the memory of those who witnessed it,” attested an Iowan. “It was a harvest of death,” wrote a somber soldier in the 100th Indiana. “We moved a few bodies, and there was a boy with a broken arm and leg—just a boy 14 years old; and beside him, cold in death, lay his Father, two Brothers, and an Uncle.” “I was never so affected at the sight of wounded and dead before,” added a man in the ranks of the 103rd Illinois. “Old gray haired and weakly looking men and little boys, not over 15 years old, lay dead or writhing in pain.”

“I could not help but pity them as they lay on the ground pleading for help but we could not help them as we were scarce of transportation,” explained an Indiana soldier to his wife. “The field was almost covered with dead and wounded,” contributed a member of the 100th Indiana, “some crying for water, some for an end to their misery.” “We took all inside our skirmish line that could bear moving,” said an infantryman in the 103rd Illinois, “and covered the rest with the blankets of the dead.” Other squads broke up captured arms or brought in

uninjured prisoners. “They were badly mixed up in age, ranging all the way from 14 to 65 years,” said an Iowan. Among them were several black slave-servants.

Top priority for the Yankees was taking care of their own, as there were both wounded and killed in Union blue. Among the latter was Corporal Aaron Wolford, an older man in the ranks of the 100th Illinois, whom the younger soldiers had fondly called “Uncle.” Wolford, who had expressed a premonition of his death the night before, fell early in the combat, shot through the head. His comrades fashioned a rude coffin out of a hollow sycamore log to lay him to rest. Another officer present noted that his men buried their dead, placed the wounded in ambulances, and marched that same night. By midnight only Georgians remained alive on the field east of Griswoldville. One of the last Union soldiers to depart remembered the “mournful sighing of the wind among the pines and the pitiable moans of the wounded and dying.”

When the time came to set down the history of this encounter, both sides put their spin on the story, even though most of those who had been through the ordeal fully understood what had happened. Wrote a Confederate participant: “The Militia has been in a very hard fight and got badly whipped.” Yet Southern writers, beginning with newspaper reports published within days, stressed that Philips withdrew from the enemy without challenge, that the part-time soldiers had acted with “distinguished gallantry,” and that “both sides suffered severely.” Northern historians doubled and tripled the size of Philips’s force, applying a similar multiplier to his casualties, which, in some estimates, approached 2,000. Federal record keeping was fairly thorough, so Walcutt’s losses can be stated with a certain confidence at 13 killed and 86 wounded. Confederate tabulations were much less comprehensive, so here the losses are estimates only: about 50 killed and 500 wounded.

Over the next few weeks, a number of local newspapers dutifully printed letters from some participants containing lists of the injured and dead. The doleful registers filled column after column, often providing the only notification that families or loved ones would receive. In one such column, readers of the

Macon Daily Telegraph and Confederate

learned on November 24 of the battle’s impact on the 7th Georgia Militia Regiment, whose commander had been killed. Among the

forty-eight individuals listed: T. G. King and J. C. McLeans were dead, William Evans had a slight foot wound, Sergeant D. H. Henly had serious wounds in the thigh and leg, Jack Bussey was hit in the shoulder, William F. Williams in the breast, and M. K. Wilcox was severely wounded “and supposed killed.”

Brigadier General Philips remained convinced that had his orders to assail both Union flanks been properly executed, “it would have resulted in dislodging and probably routing the enemy.” Although in public Major General Smith praised Brigadier General Philips for his “success in driving before you the enemies of your country,” in his official report he complained that the entire fight happened despite his orders “to avoid an engagement at that place and time,” and that all things considered, “the troops were very fortunate in being withdrawn without disaster.”