Southern Storm (27 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

Although Brigadier General Philips had authority over the militia and State Line, the local defense battalions reported to another chain of command, which soon created a problem. Once Griswoldville had been swept clear, Philips was informed by Major Cook that his orders (direct from Lieutenant General Hardee) were to proceed along the tracks to pick up transportation to Augusta, which he intended to do. Lacking any plan of his own, Philips agreed to move everyone through the town. They would march together as far as Griswoldville’s east side, where he would halt to seek fresh instructions from Macon.

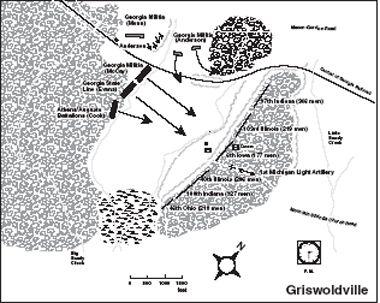

The slight ridge along which Walcutt’s brigade deployed was bisected by a road stretching east to Mountain Springs Church. Walcutt had used the passageway to split his brigade, placing three regiments south of it (left to right: 46th Ohio, 100th Indiana, 40th Illinois) and three on the north side (left to right: 6th Iowa, 103rd Illinois, 97th Indiana).

*

A two-gun section from the 1st Michigan Light Artillery, Battery B (Captain Albert F. R. Arndt commanding a pair of smooth-bore Napoleons), was posted along the lane, tucked into a hastily constructed lunette. Walcutt established his headquarters in an abandoned farmhouse located just north of the cannon. Although owned by Samuel Griswold, the property was known locally as the Duncan farm after a previous resident.

Some Union skirmishers spooked by Philips’s advance scooted out of the far woods to scamper across the broad open field to where Walcutt’s brigade was resting. Major General Osterhaus’s injunction to erect defensive works had been halfheartedly implemented at best. Word that a sizable body of Rebel infantry was approaching Griswoldville provided much-needed motivation. “We gathered rails, logs and anything we could get for protection,” recalled an Iowan. “We were getting dinner, not dreaming of a fight,” seconded an Illinoisan.

The skirmishing gunfire crescendoed in the timber; after a few minutes the field was abruptly dotted with scurrying, hunching figures as the rest of the Federal skirmishers broke cover to skitter toward the Duncan Farm ridge. Now the barricade-building got going in earnest. Said a private in the 103rd Illinois: “We used everything that would check a ball.”

The passage of the Georgia state troops through Griswoldville presented the men with disquieting images of the shape of things to come. At its peak of operation, the neat village was something of a showcase for the South’s future. Beside the cotton gin manufacturing plant converted to revolver production, the town had boasted brick, soap, and candle factories, a saw-and gristmill, and various shops and quarters for white and black workers. Of the forty-odd structures, now only the two-story wood-frame Griswold mansion and a few other dwellings remained intact. All the others were burned or wrecked to a significant degree. It was a sobering vision of what might happen to Georgians’ homes if the Yankee marauders were allowed to operate unchallenged.

There was gunfire near the head of his column, causing Brigadier General Philips to ride forward to meet once more with Major Cook, who informed him that his men had bumped into another line of Yankee skirmishers. These too had been easily driven, chased through the woods across a large fallow field into what looked like a defensive position. The officers and their staffs eased up to the timber’s edge, where Cook pointed off to the east. Philips saw, as he later reported, “the enemy posted on the opposite eminence in line of battle behind some temporary intrenchments and fortifications.” The militia brigadier decided to bring his command up in battle formation. Counting everyone—militia, State Line, local defense units, and artillery—he had 2,300 to 2,400 men on hand.

Major Cook’s battalions of local defense troops, at the head of the column, formed the right flank. In the center Philips put his steadiest infantry, the two Georgia State Line regiments. A pair of militia brigades made up the left flank, with a third held in reserve. The four-gun battery (Captain Ruel W. Anderson in charge of 130 men, with Lieutenant Henry Greaves handling the cannon) was sent to “an eligible

site on the railroad on the north side.” Almost immediately after getting into position, the veteran gunners began shelling some Yankee cannon they could see on the far side of the fallow field, where the road reentered the woods.

It was at this critical juncture that a staff officer carrying dispatches from Macon found Brigadier General Philips. The first message, from Major General Smith’s chief of staff, after alerting him that Wheeler’s cavalry had departed the area, instructed Philips to “avoid a fight with a superior force.” A second dispatch, from Smith himself, had been added after Major Cook’s first sighting report had reached Macon. “If pressed by a superior force, fall back upon this place without bringing on a serious engagement, if you can do so,” Smith advised.

In what remained of Griswoldville, the Macon staff officer composed a situation report for delivery to Major General Smith: “GENERAL: The whole division, including Cook’s battalion, is one mile in advance of this place on the Central railroad, in line of battle, with the State Line troops thrown out in front skirmishing with the enemy. Anderson’s battery opened upon them just as I rode up to the line, the enemy’s battery replying. General Philips does not know what their force is, and, on receiving your instructions, concluded not to advance farther. On the movements of the enemy depends whether or not he will fall back to this place or remain where he now is.”

Brigadier General Walcutt waved over Captain Albert Arndt, commander of the 1st Michigan Light Artillery, Battery B, whose two-gun section was assigned to this expedition. Walcutt indicated a party of enemy soldiers visible at the edge of the woods to the right of a log house and told the gunner to do something about it. Arndt rode the short distance back to his guns, where he ordered the section commander, Lieutenant William Ernst, to target the group. Ernst called out the commands, aimed the two cannon at the distant figures, and yanked the lanyard. The shells landed close enough to cause the enemy soldiers to melt back into the woods, so Arndt ordered a ceasefire.

Their appearance provided the officer with a point of reference for the enemy’s possible advance, and he realized that he should shift one of the guns more to the right to set up a crossfire. Another quick visit to Brigadier General Walcutt secured the necessary permission, but

even as the captain returned to reposition his artillery, the equation was changing. Four Rebel cannon emerged from the woods, expertly swung into firing positions, then opened on his pair. An Iowa soldier crouching nearby was impressed as the enemy’s initial round smashed into one of two caissons carrying munitions, resulting in an explosion that destroyed about half of Arndt’s immediate supply.

The first enemy volley also accounted for the Union battery commander. One moment Arndt was assessing the situation, the next he was flat on his back, “lying behind a [tree] stump with one of my men leaning over me unbuttoning my clothes.” Stunned by the nearby explosion and believing himself to be fatally wounded, Arndt told the gunner to leave him and help his battery mates. Even as the officer felt himself growing woozy, the air around him was filled with the sharp crack of explosives and the vicious hiss of shrapnel as enemy rounds continued to pummel the Michigan cannon.

Confederate brigadier Pleasant J. Philips now faced one of the most difficult and controversial decisions of his military career. Even as the various regiments and companies making up his composite division moved into places along the tree line, Philips had to decide whether or not to attack. While he had assured Major General Smith’s aide that he had no intention of going over to the offensive, Smith’s orders had provided the option of doing just that as long as he wasn’t being “pressed by a superior force.” He wasn’t. The Federal infantry blocking his way had made no aggressive moves save for the feeble effort of two Yankee cannon, smothered by the counterbattery blast from Captain Anderson’s iron quartet. The open field his men would have to cross was far from flat and level; in fact, two small branches of Big Sandy Creek wriggled north to south, providing sheltered resting places for any advancing line of battle. Its relative openness would also make it easy for the militia units to maneuver, since most had been trained in farm fields such as these.

Philips doubted that the enemy would make a stand here. So far, the U.S. soldiers had demonstrated a marked disinclination to fight, preferring to fall back when pressed, especially as they had done at Griffin and Forsyth. Philips knew from Hardee’s assessment that the Federals, no longer targeting Macon, were likely moving toward Milledge

ville, so the thin line of enemy infantry across his path was probably a rear guard that would fade away at first push.

Also part of his calculation was the mood of his men. Many had been marching constantly since the campaign opened, abandoning swaths of territory for the enemy to ravage. There were companies in the gray ranks drawn from many nearby areas—Jones, Wilkinson, and Bibb counties, as well as Macon itself—with others from farther away—the towns of Athens and Augusta, as well as Montgomery County, toward Savannah. While not exactly itching for a fight, they were determined to defend their state, tired of those who challenged their courage. According to one Confederate officer, the militiamen dreaded the “jeers and sneers they must encounter…more than they do the bullets of the Yankees.”

Philips came to the conclusion that the circumstances justified an attack, though he would never share his precise reasoning or proffer any justification for the decision. The plan he settled on was big on simple and direct; his flanks would turn the enemy flanks, while his center would tackle the Federal center. In the only report he would write of this day’s actions, his sole comment was that “an advance was ordered.”

Recollected an Iowa foot soldier across the way: “The enemy’s forces marched out of the timber into the open field with three lines of infantry, either one of which more than covered the brigade front. Their lines were pushed boldly forward, with colors flying and loud cheering by the men, presenting a battle array calculated to appall the stoutest hearts.” The martial panoply might have had the desired psychological impact had the opposition been raw troops, but it was a wasted gesture given the nature of these soldiers. “The enemy advanced in three columns,” remembered another Iowan, “but the boys who had fought so many battles with Sherman were not frightened at superiority of numbers.”

Captain Anderson’s Georgia gunners had wreaked havoc on the two Michigan cannon opposing them, clearing the way for the infantry attack. By the time Captain Arndt realized that he wasn’t mortally wounded (the fragment that hit him had been deflected by his saber belt plate, leaving him bruised but otherwise okay), his battery had been savaged. His fourteen men paid a terrible price for sticking with

their guns—two lost legs, one an arm, and four more were wounded to various degrees. Even as the still dazed officer watched, one of his gunners, William Plumb, gamely continued to perform his duty even “after the sponge and rammer had been shot to pieces.” Although Arndt later reported that he had maintained his position until “the last round of ammunition was fired,” evidence suggests that he ordered his tubes out well before the Rebel battle line came within killing range. With six of his horses also down, Arndt’s men had to haul the cannon away by means of ropes harnessed to human backs.

Freed of their only real threat, the Rebel cannoneers now ranged freely along the Union line. The Georgia artillerymen, noted an Illinoisan, “made the rails and logs fly pretty lively.” “The enemy’s well served artillery continued to do serious damage along the entire line of the brigade,” seconded a member of the 6th Iowa. “A single shell that struck and exploded in the rail and log barricade at the point where the regimental colors were waving [killed a member of the color guard]…blowing the top of his head off and saturating the colors with his blood.”

As the first, then the second, and finally the third lines of battle emerged from the woods, they were greeted only by the spattering fire from Yankee skirmishers who had holed up in the ruins of some farm buildings located outside the main line of resistance. The militiamen, State Line soldiers, and local defensemen moved steadily, finding comfort in the close presence of neighbors and friends. “The rebel infantry approached…at shoulder arms, in good order, as if on parade,” recorded one admiring Federal. The Union main line was ominously quiet. “We charged them but were ignorant of their numbers and advantage,” declared a member of the Georgia State Line. This state of affairs lasted until the first line was about midway across the field. Then the Yankee position began blinking with gunfire. The time was about 2:30

P.M

.

“The music of shot and shell soon began,” wrote an Indiana soldier. “As soon as they came in range of our muskets a most terrific fire was poured into their ranks, doing fearful execution,” reported the commander of the 103rd Illinois. This first volley, fired at 250 yards, recorded another member of the regiment, “was most terrible; literally mowing down the first line, which halted, wavered, and seemed amazed.” Although the majority of Federals were armed with standard single-shot muzzle-loading Springfield rifles, within each Union regiment were special squads of picked men carrying rapid-firing breech-loading rifles. This, allowed an Indiana soldier, “enabled us to keep up a continuous fire.” According to a rifleman in the ranks of the 6th Iowa, “we ‘shot low and to kill.’”