Southern Storm (59 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

To: Commander of U.S. Navy Forces,

Vicinity of Savannah, Ga.

HEADQUARTERS DEPARTMENT OF ARMY OF TENNESSEE,

Near Savannah Canal, Georgia.

Sir: We have met with perfect success thus far. Troops in fine spirits and near by.

Respectfully,

O. O. Howard

Major-General, Commanding

Captain Duncan states that our forces were in contact with the rebels a few miles outside of Savannah. He says they are not in want of anything.

Perhaps no event could give greater satisfaction to the country than that which I announce, and I beg leave to congratulate the United States Government on its occurrence.

It may, perhaps, be exceeding my province, but I can not refrain from expressing the hope that the Department will commend Captain Duncan and his companions to the honorable Secretary of War for some mark of approbation for the success in establishing communications between General Sherman and the fleet.

It was an enterprise that required both skill and courage.

I have the honor to be, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J.A. Dahlgren,

Rear-Admiral, Comdg, South Atlantic Blockading Squadron

Declared a member of the admiral’s staff: “The excitement, the exhilaration, ay the rapture, created by this arrival, will never be forgotten by the officers and crews of the Federal vessels who saw the beginning of the end of the war.” Dahlgren’s covering note, along with Howard’s brief communication, was immediately put aboard a fast ship headed north. An officer on board later told a reporter that the entire fleet was firing a salute as they departed, “and the vessels were decorated with flags.”

Along the U.S. lines outside Savannah, “the Corps and Division Commanders are getting their troops gradually in front of the rebel lines as far as yet known,” recorded Major Hitchcock at Sherman’s headquarters. Most were cautious probes, but one division commander, Brigadier General John W. Geary in the Twentieth Corps, planned a two-brigade assault on a Confederate fortification in his front. The selected troops were roused at 2:30

A.M

., then moved into a swamp bordering the objective preparatory to the charge. Apprehensions went up several notches when word spread that the water in the front was nearly neck deep. Finally, at 4:30

A.M

., the attack orders were canceled. Sputtered one well-soaked Ohioan: “Ambitious Geary baffled again!!!”

For many of those not engaged in siege activities, the name of today’s game was “Find the food.” It wasn’t that the army was out of supplies, it was just that what was on hand was not appealing to men accustomed to the rich variety enjoyed during the march. For instance, there remained a sizable beef herd, but the quartermasters always killed the

most scrawny beasts first, leading one soldier to complain that they were getting “

dried beef on foot

.”

Some Wisconsin boys got an unexpected education in differing cultures when they visited a community of slaves recently arrived from Africa, where they were given rice cooked with a tangy meat. The soldiers’ pleasure was ruined when they learned that the distinct flavor came from chicken entrails—often the only portion of the bird allowed the blacks by their owners. Along the section of the line held by the 39th Ohio, the Buckeyes were taunted by Confederate pickets, who boasted that there was plenty of bacon in their camps. A Federal present recalled that “one of our boys replied if you have so much bacon why in hell dont you grease your britches and slide back into the union?”

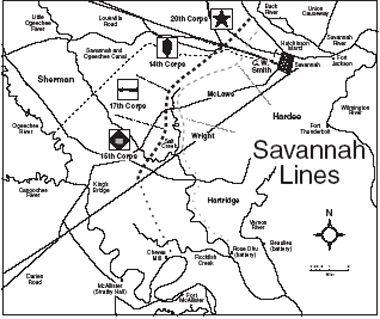

Since the various corps had approached the main line of resistance in something of a pell-mell fashion as their differing routes of march converged, some readjustment of positions was necessary to tidy up the deployments. The late-arriving Fourteenth Corps today occupied a section previously held by the Seventeenth, which slid to the right.

One group of Major General Blair’s infantry and artillery had to choose either a long roundabout march out of range of the enemy’s guns, or a shorter path across their sights. The officers opted to wait for nightfall to risk the direct passage.

Those involved described the experience as either running the “blockade” or the “gauntlet.” “As soon as it was nearly dark we moved out,” recollected an Ohio infantryman, “making as little noise as possible and just before merging into the open plain we were ordered to carry our arms muzzle downwards so they could not be seen and not to speak above a whisper lest the Rebel battery should open up.” The infantry went first, followed by the artillery. “You may judge of our feelings as we he[a]rd time and again of the strength of the [rebel] fort and that it was near to our rout[e],” said a member of the 1st Minnesota Light Artillery. “We pass at a quick walk and they only fired 5 times at us and did not hurt one of us. But you ought to see the heads bow, when we saw the flash of the guns.”

On the far left of the Union siege lines, the tedious process of getting the 3rd Wisconsin transferred onto Argyle Island was further slowed by dramatic events. A short distance above where the dogged Midwesterners were about to resume crossing twenty at a time, a Federal battery had taken a position on the river bluff, supported by the 22nd Wisconsin. It was still before dawn when infantry lieutenant W. H. Morse made his way about a mile north of the camp to check on an outpost. Once there he “spied a light some distance up the river which appeared and disappeared several times. I waited and watched and soon I saw smoke, and, daylight approaching, I saw the vessels.”

The boats in question, part of Savannah’s ad hoc naval squadron, consisted of the gunboats

Sampson

and

Macon,

accompanied by the tender

Resolute

. They had initially been ordered up the river from the city to protect the Charleston and Savannah rail bridge, but once it became evident that Sherman’s men were astride the line, new orders came to destroy the span. With that mission completed, Lieutenant General Hardee had recalled the craft to Savannah in order to add their firepower to the city’s defenses.

Sampson

was leading the column, followed by the

Resolute

and the

Macon.

It had proven to be a sobering journey for the Confederate sailors. “As we went along we saw at the different places smoking ruins,” reported the squadron’s commander. Intelligence gathered from

civilians met on the way suggested that the Yankees had yet to establish any artillery positions along the riverbank.

In fact, the four rifled Parrott cannon guarded by the 22nd Wisconsin had been rolled into position on the Colerain plantation just the previous afternoon. The tubes represented Battery I of the 1st New York Light Artillery, Captain Charles E. Winegar commanding. On paper the Confederate squadron’s heavier-caliber guns seriously outmatched what the Federals had, but Winegar had picked a good spot for his cannoneers. They were positioned on a bluff in a bend of the river where the channel narrowed, forcing the enemy craft to approach head-on, significantly limiting how many of their weapons could bear on the target. Still, the Confederates knew their business. As the three vessels drew within range, the

Macon

swung out somewhat to starboard to unmask its forward piece. Captain Winegar, a Gettysburg veteran, opened fire at 2,700 yards, while the gunboats remained menacingly silent until within 800 yards.

Winegar’s opening shot was somewhat anticlimactic, bursting in the air well short of the targets. This brought some unsolicited advice from the Wisconsin colonel to the New York captain that he was cutting his fuses too short. Winegar retorted that he was using percussion shells, which exploded on impact, and guessed that a defective firing pin caused the premature detonation. The rest of the colonel’s boys were well under cover and enjoying the fireworks display. A member of the regiment recollected most of the enemy’s return fire “falling short, but some struck in the bank just under the battery, and some went high above us…. None of us were hurt in the least, for when we saw the white smoke from their guns, we either jumped down behind our breastworks or got behind the big trees near the shore.”

No one counted how many times the

Sampson

and

Macon

fired, but Captain Winegar logged 138 rounds from his guns. The fact that the Confederate craft, approaching head-on, were essentially stationary targets, simplified the firing solution for the Yankee cannoneers, who scored with 5 percent of their shells. The Rebels scored no hits, even though a midshipman aboard the

Sampson

recollected a “terrific fire” from both sides. As later reported by the Southern squadron commander,

Sampson

“was struck three times—on her hurricane deck, near machinery and steam drum, and once in her rudder…. C.S.S.

Macon

was struck twice, once under her bow and one shot passing

through [her] smokestack. C.S.S.

Resolute

[was] struck twice, one shot injuring her wheel so as to disable her.” Hoping to push through to Savannah before the Federals closed the river, the Confederates had instead run into a hornets’ nest. It was evident to the squadron commander that “we could not pass the batteries.”

Orders were given for the three ships to reverse course. Struggling to maneuver in the narrow channel while still under fire,

Sampson

collided with

Resolute,

“damaging both vessels.” Adding insult to injury, the

Macon

also sideswiped the tender making its U-turn. “The C.S.S.

Resolute

being unmanageable, drifted ashore [on Argyle Island],” continued the squadron commander’s report. “It being impossible to render her any assistance without endangering the safety of the other vessels from the fire of the enemy…, we were compelled to leave her, with orders for the crew to escape in their boats if it was impossible to get her off.”

The frantic efforts by the crew of the

Resolute

to lighten the craft by throwing every loose object overboard was observed with very great interest by some recently arrived spectators on the shore—Company F of the 3rd Wisconsin, which had hurried up Argyle Island from where the rest of the regiment was crossing from the Georgia side. The Wisconsin boys were enjoying the spectacle when the Rebel sailors signaled their intention to abandon ship by piling into two lifeboats. At this several riflemen waded into the shallows, parted the reeds, and called out: “Turn back, Cap, turn back.” When the captain of the

Resolute

ordered his men to continue rowing, he was shot in the shoulder for his trouble, which was enough to convince his men to surrender. A couple of overeager infantrymen waded into the neck-deep water to take possession. The Wisconsin colonel in charge later tallied five naval officers and nineteen sailors taken prisoner.

The

Macon

and

Sampson

successfully steamed the 200 miles to Augusta, though they were reduced to burning bacon in their boiler furnaces to finish the home stretch. The

Resolute

itself was repaired by its captors, and despite stories that it was burned shortly thereafter, actually remained in U.S. service throughout the siege, providing useful services transferring troops and supplies. Chatting afterward with Major Hitchcock, Captain Winegar bragged that this was “the first

naval

engagement he ever took part in, and that he wants more of the same sort.”

Just about all that Sherman could think about now was Fort McAllister; so, after seeing the Cuyler brothers on their way, he rode to Major General Howard’s headquarters to be closer to the action. Work on King’s Bridge was continuing, with Captain Reese expecting to be finished early on December 13. Security on the opposite bank was now courtesy of Brigadier General Kilpatrick’s First Brigade, which had crossed the Ogeechee higher upriver, followed by a crossing of the Canoochee on a hastily re-erected pontoon bridge to get there. His advance detachment had surprised Fort McAllister’s commander, Major Anderson, who was undertaking a scout of his own. “We were hotly pursued by their cavalry,” Anderson later reported; nevertheless, the detail accompanying him had time enough to burn two barns full of rice and a steam tug anchored three miles above the fort.