Stonehenge a New Understanding (35 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

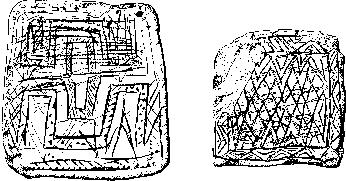

The chalk plaques found in a pit east of Stonehenge, during road widening in 1968. The small plaque is 56 millimeters across.

On the east side of King Barrow ridge, not far from the Stonehenge Avenue, Julian Richards found an area of pits and stakeholes that may be the remains of Neolithic houses, associated with lots of chisel arrowheads lying on the surface of the plowed field.

6

Radiocarbon dates from animal bones indicate that the area was in use around the same time as the cursuses (before the building of the village or henge at Durrington

Walls), though shards of Grooved Ware also hint at later activity, perhaps in the earlier third millennium BC. This area might have been a gathering place for people building the cursuses around 3500 BC and, perhaps, for building Bluestonehenge and the first stage of Stonehenge around 2950 BC.

One of the chalk plaque fragments from Durrington Walls. This was the most elaborately decorated artifact found in the Neolithic village.

One of the major lessons of finding Bluestonehenge was the realization that there are probably still plenty of sites around Stonehenge waiting to be found. Some, like a pit circle found by Wessex Archaeology off the west end of the Lesser Cursus in 2009, will turn up during conventional geophysical survey or aerial reconnaissance. To locate others will take some real detective work as well as luck, in much the same way as our own efforts eventually resulted in the discovery of this unknown henge.

Colin has plotted the distribution of bluestone chippings across the Stonehenge landscape and wonders if some relate to other lost stone

circles. As well as the concentration at Fargo, he has noted various pieces at Coneybury henge, and in the fields north of the Cursus, and at a site called North Kite. North Kite is very peculiar; it is a large three-sided enclosure built in the Beaker period (around 2400–2000 BC), about a mile southwest of Stonehenge.

7

When Julian Richards dug a trench through its west bank, he found three chips of spotted dolerite on its buried ground surface. Julian has never thought much of them, but Colin is not so sure that North Kite should be dismissed without a closer look. Any fragments of bluestone found in this landscape are of great importance: Since the bluestones came from Wales, and do not occur naturally on Salisbury Plain, such fragments indicate nearby prehistoric human activity.

Finding Bluestonehenge not only opened our eyes to the potential for future discoveries around Stonehenge, but also demonstrated that the Stonehenge Riverside Project was on the right track. It certainly justified the project’s title, and confirmed that any interpretation of Stonehenge must take into account the River Avon and its relationship to sites upstream, such as Durrington Walls and Woodhenge.

What was the purpose of Bluestonehenge? Was it just a stone circle where people gathered, or were other activities happening here? The almost complete absence of pottery and animal bones from the henge shows that this was not a place where people lived, despite its attractive location beside the river. Our excavations showed that erosion of the henge surface has left no buried ground intact from the time of its use, but there was one way of finding out what went on here when the stone circle was in use.

After the stones of the Bluestonehenge stone circle were extracted, the voids left behind then filled up with topsoil and turf, collapsing in from the uppermost edges of the stoneholes. As well as providing evidence for the riverside environment, this soil filling the stoneholes contains further clues about the activities performed on the ground surface among the stones. There is a lot of wood charcoal, from tiny pieces to a fist-sized lump: Fires must have been lit in the vicinity of the stones, perhaps inside the circle.

Perhaps the fires were pyres for cremating the corpses whose ashes were buried at Stonehenge—but we’ve found no cremated bones among

the charcoal. In one of the stoneholes we did find a fragment of an unburned pig humerus (bone from the upper front leg) dating to 2670–2470 BC. This is particularly interesting because it is from the same period as Durrington Walls village and the sarsen phase at Stonehenge. It probably fell into the hole from the ground surface where, by the look of the pitting and cracking of the bone’s surface, it must have been lying around for years if not decades.

Once upon a time, the site of Bluestonehenge was a settlement, but this was long before the people of the Neolithic came here. In the mud underneath where the henge bank had been, Jim and Bob found a dense spread of flints. These were all mixed together in a single layer, but they include microlithic flint blades from the Late Mesolithic and larger blades from the Early Mesolithic, the periods before the Neolithic. Thousands of years before Stonehenge, this riverside spot was a campsite for hunter-gatherers living off the resources of the river and its margins.

Today a spring rises north of the chalk promontory at West Amesbury, on which Mesolithic people once camped, and on which Bluestonehenge once stood. Back then, when the water table was higher, the springhead was probably much further up the valley—perhaps not far from the Neolithic settlement on the slope of King Barrow ridge—so a stream would have flowed here. On its north bank, our test pits found more Mesolithic flints. We had located one of the campsites that could have been used by the people who put up those pine posts nearly ten thousand years ago.

By the time our excavations finished in 2009, we had come a long way. After seven years of searching, we’d found out a lot about Stonehenge, mostly by looking at its context—its landscape—as well as by re-evaluating what had already been found within Stonehenge itself.

15

__________

One of the most incongruous aspects of Stonehenge today is the presence of a major road, the A303, running within 150 meters of its southern edge. At the point where it passes Stonehenge, this busy road has only a single lane in each direction, and on Fridays it is packed with long queues of drivers escaping London to spend the weekend in the southwest of England. And they must all come back again on Sunday night, for a second wait in the traffic jam.

Since 1992, the British government has been wondering what to do about this. As well as the economic cost of the traffic jams (there are formulas used to work such things out), this road is seen as a blight on one of the United Kingdom’s very few World Heritage Sites. New routes involving moving the road to the north or south of the monument have all been considered and all ultimately rejected. In the late 1990s, the Highways Agency proposed that the A303 beside Stonehenge should be hidden in a tunnel, constructed by the cut-and-cover method, in which a broad corridor of land would be stripped away and a tunnel created by covering a new, sunken roadway with a grassed-over concrete roof.

The cost of this method looked relatively inexpensive—much cheaper than boring a tunnel—but it would require a very large swath of land close to Stonehenge to be archaeologically excavated and then entirely removed in advance of construction. There was much opposition to the proposal, from a spectrum of interest groups ranging from local residents to those concerned with the wildlife of Salisbury Plain. Many archaeologists worldwide objected to the scheme because it would utterly

destroy a huge slice of archaeological remains within the World Heritage Site, over an area so large that it would make the 1968 new road cut through Durrington Walls look tiny.

The government backed down and agreed to pursue the less damaging but far more expensive option of a bored tunnel. In 2004, the Highways Agency presented its proposal at a public inquiry in Salisbury. Archaeologists and conservation bodies were divided in their views. English Heritage backed the scheme strongly but the National Trust and many others thought the planned tunnel was too short: The proposal on the table was for a 2.1-kilometer tunnel through the 5-kilometer-wide World Heritage Site, which would require long and deeply embanked approaches leading into it; in addition the ground level in Stonehenge Bottom would need to be artificially raised to accommodate its height. Feelings ran high among archaeologists: For some, this deal—albeit imperfect—was the best that Stonehenge would ever get; for others, it was a half-baked solution, and the road problem was best left alone until the job could be done properly.

In his report, the planning inspector gave the green light for the short tunnel. By that point, though, the cost of implementing the scheme had doubled, to around £500 million. A particular cause for concern was the state of the chalk deep below Stonehenge—it appeared to be unstable, and expensive techniques would be required for its safe removal. Even at the height of the early 2000s’ economic boom, the British government couldn’t afford it. For those who like to know the price of everything, this was more than Stonehenge’s scenery was worth. It is estimated that the government had to spend more than £30 million on consultants and lawyers’ fees for us all to end up exactly where we started. Fortunately, a tiny proportion of that money did go into something of lasting value.

As part of their proposal, the Highways Agency commissioned archaeological contractors to carry out field evaluations along the proposed road line. A huge strip of land immediately to the south of Stonehenge, from one end of the World Heritage Site to the other and even beyond, was given a magnetometer survey and also trial-trenched. Even though the long, thin, machine-dug trenches only represented about 2 percent of the proposed road corridor, the total area excavated by these two

hundred or so trenches was vast—the greatest area ever excavated within the World Heritage Site, except for the 1967 dig at Durrington Walls. The results were an almost total blank.

1

The only new prehistoric feature of any significance was one Beaker burial.

There is an absolute rule in archaeology that absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. There could once have been prehistoric remains here, since destroyed by plowing, for example. However, the absence of Neolithic, Copper Age, or Early Bronze Age pits—what we now know to have been integral to settlements such as Durrington Walls—makes it likely that nothing of importance was missed by these trial trenches. The excavators concluded that this area to the south of Stonehenge had been largely devoid of activities, monuments, or settlement sites in the fourth to second millennia BC.

Years before, archaeologists had noticed that Stonehenge sits at the center of an area, up to a mile across, that contains far fewer Bronze Age round barrows than the areas slightly further out from the stone circle. The round barrow cemeteries are concentrated in a wide, doughnut-shaped circle on the skyline around Stonehenge.

2

They sit on the edges of a central, empty envelope of visibility immediately around the stone circle, within which there are fewer than forty barrows. Since the trial trenches were within the envelope of visibility, their emptiness supports the existing evidence that this area closely encircling Stonehenge was deliberately avoided both by Neolithic and Copper Age inhabitants of the area, as well as by the Early Bronze Age builders of the round barrows.

As our own excavations at Durrington Walls came to an end, our next task was to look at the landscape west and north of Stonehenge for evidence in this area of settlements occupied at the time of Stonehenge. Julian Richards’s survey team had recovered lots of worked flints, including Neolithic arrowheads, from a large field on the rising ground immediately to the west of Stonehenge.

3

Here, in fact, was one of the two densest concentrations that he found in the entire survey area.

We also hoped to solve a mystery that had arisen when the visitor center was installed in 1967. Back then, Lance and Faith Vatcher had carried out a small dig and found the end of a long, straight ditch heading off from the parking lot area southward, past the west side of Stonehenge,

which had held a palisade of closely spaced timber posts.

4

The Vatchers found nothing to date the ditch or the palisade, but they knew that the timber posts were long decayed by the time that a man’s corpse was buried in the ditch terminal at some time in the period 780–410 BC (the Early Iron Age). There was a possibility that this timber palisade was part of a huge Neolithic enclosure, like the ones dug by Alasdair Whittle at West Kennet, near Avebury, in 1987 and 1990—Josh had been there, too, on the team as a student.

5

If this was a Neolithic enclosure, it could have contained a large settlement.