Stonehenge a New Understanding (38 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

We now had a quite unexpected new interpretation of Stonehenge, and an explanation for why it was positioned here. At some point in the very distant past, around ten thousand years ago, hunters in search of

game on the grasslands of Salisbury Plain came across a series of ridges and stripes in the ground. Perhaps they already had an understanding of the sun’s annual movements and realized that, in this particular place, the axis of midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset was tracked by ancient marks in the land. Here, heaven and earth were unified by some supernatural force. Around it, they camped, dug pits, and erected pine-tree posts, marking the direction of the highest hill on the horizon.

Perhaps the traditions associated with this place continued, though it’s more likely that they died out and people forgot. In the intervening millennia, between the end of the Early Mesolithic and the building of Stonehenge around 3000 BC, this location seems not to have attracted interest. Early Neolithic monuments of the fourth millennium BC—long barrows, cursuses, and a causewayed enclosure—were built on nearby spots but not here. Rather than there being any continuity of meaning and memory between the Mesolithic posts and the building of Stonehenge five thousand years later, it is more probable that Neolithic people rediscovered this curious geological phenomenon around 3000 BC, perhaps ascribing it to the actions of supernatural beings or a world creator. They might have noticed the prominence that we call Newall’s Mound. The large sarsen that we call the Heel Stone was probably lying recumbent at the south end of the stripes in the ground. There, facing the midwinter sunset, they constructed a circular enclosure, whose roundness echoed that of the sun and moon, with a circle of Welsh bluestones and a burial ground for the most illustrious of their dead.

If these natural features were the first phase of the avenue, when were its ditches and banks constructed? Four radiocarbon dates have been obtained from antler picks and a cattle bone found in or near the ditch bottom during previous excavations; but, because the ditches were emptied out at some point in prehistory, and thus all the built-up silt and soil inside them removed, it’s difficult to tell whether these picks and bones ended up in the ditch the first or second time that it was dug out.

As we excavated beneath the shallow banks of the avenue, we discovered that the Neolithic ground surface had been protected underneath them. It was littered with chippings of sarsen and bluestone. The presence beneath the banks of this stone-dressing waste means that Stonehenge’s stones were shaped and put up before the avenue’s ditch

and bank were constructed. The avenue banks must therefore date to after 2500 BC, confirmed by radiocarbon dates of antler picks on the ditch bottom dating to 2500–2270 BC.

About 70 meters west of our avenue trench, Colin was digging a small square trench just five meters across. He was hoping to find evidence for the shaping and dressing of the stones before they were taken the last few hundred yards to the stone circle. His enthusiasm for molehills, generated all those years ago as an evening-class student, has never left him. Every time we stroll around this field in front of Stonehenge, he gets everybody to look in the small heaps of loose soil. Immediately east of the visitor center, Colin had found sarsen chippings brought to the surface by those moles. When he returned year after year he was able to see that a very extensive area in front of Stonehenge was producing chippings from the stones. The density of chippings is greatest on the field’s west side, where it was plowed during the 1970s.

Colin consulted the records of the parking-lot and visitor-center excavations in 1935 and 1967. Although they had dug carefully, Young and Newall, and the Vatchers had found very few stone chippings—though it’s clear from their records that they had been looking for them.

13

In contrast, Mike Pitts had found loads in his cable-trench excavation in 1980 on the other side of the road.

14

Kate Welham carried out a resistivity survey in the molehill field, the results of which were great. We could see a skirt-shaped zone of high resistance stretching westward from the beginning of the avenue to the area plowed in the 1970s, close to the visitor center. We were sure that this high resistance was being caused by a pavement-like spread of broken stone. We could hear the crunch of metal hitting sarsen as Mike Allen cored a series of auger holes across the spread, from which we picked out tiny chips.

We were sure that we’d found the stone-dressing area where the sarsens were worked. They must have been dragged here from the quarries, already roughly shaped but awaiting their final smoothing. Perhaps they were also lined up on their wooden cradles and their dimensions checked, to make sure that lintels would fit on top of uprights. Then they would have been hauled on their sledges through the wide northeast entrance into Stonehenge. To demonstrate beyond doubt that this was a stone-dressing area, we needed to put a trench here.

We proposed a 15 meter by 10 meter area for the trench. This would be just big enough to reveal the silhouette left by the stone debris lying around the edges of at least one sarsen. But the National Trust wasn’t having it: It would allow only a much smaller hole five meters by five meters. We had no choice—and at least we’d been given permission to open a trench here at all. This was the only completely new area in the avenue field we were allowed to dig; all our other trenches reopened old excavations.

Beneath the turf in Colin’s trench, he came down on to a classic worm-sorted topsoil. This had not been plowed in thousands of years, if ever. Beneath it was a small piece of the Stonehenge Neolithic landscape that had survived the ravages of erosion for four or five millennia. Just as Colin had predicted, there was a carpet of sarsen chippings across the surface of the chalk bedrock. To Mike and Charly’s satisfaction, the periglacial stripes here were very narrow and shallow, confirming that the oversized stripes beneath the avenue are unique.

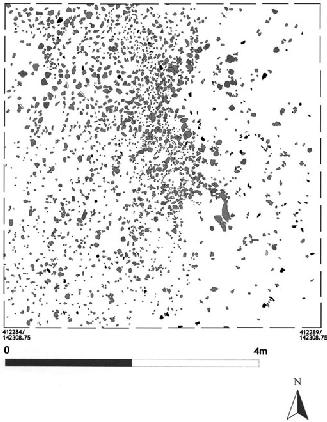

The shape and position of each stone chip as it lay in the ground was drawn on a detailed plan and then the chippings were lifted in half-meter squares for counting, weighing and careful analysis. We needed to establish that this was “primary refuse”—that the chips lay where they had fallen from the activities of stone-dressing, and that these stones had not been collected from somewhere else and dumped here in heaps at a later date.

Colin’s team included Ben Chan and Hugo Anderson-Whymark, who are experts in worked stone—whether flint or sarsen. With all the stone chips laid out across the floor of a giant agricultural barn, they found from patient trial and error that some of the pieces fit together. The pieces that fit were found lying close to each other, suggesting that they lay where they had fallen from the stone. One half of the trench had very few chippings in it, with a very obvious and straight north–south line dividing this area from the part of the trench with masses of chippings. We were looking at the silhouetted edge of a stone, where a sarsen had been laid on its back and all its surfaces, apart from its underside, pounded smooth. Had we been allowed a bigger trench, we could have seen the entire shape of the stone that had been dressed here.

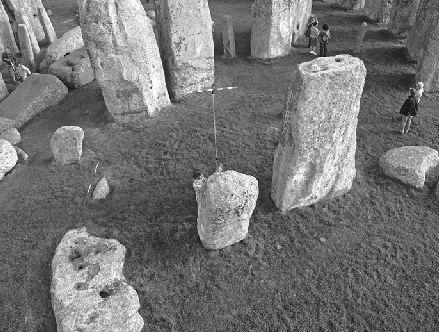

Computer specialists Lawrence Shaw and Mark Dover (standing right) visit Colin Richards’s trench immediately north of Stonehenge. Here the sarsen stones were dressed (shaped and finished) before they completed the last step of their journey.

Colin, Ben, and Hugo counted and weighed 6,500 sarsen chippings from this one trench. They also found fifty hammerstones, many of which were fractured and broken. These fist-sized hammers are made of hard quartzitic sarsen, in contrast to the generally softer stone of the uprights and lintels of the stone circle. Most of the hammerstones are round but some have been roughly flaked to make simple hand-axes, their edges battered from repeated contact with the rock. The process must have been exceedingly tedious and damaging: Anyone could have contributed to this sort of work—men, women and children—but hour upon hour of bashing hand-held rocks against the huge stones would surely have injured their wrists and fingers. Larger hammerstones, termed “mauls,” were also used in stone-dressing. Gowland, Hawley, and Atkinson all found examples of these used as packing around the bases of sarsen uprights. Perhaps these larger hammers were salvaged from the dressing zone when they were needed to pack the holes of the raised sarsens.

Colin Richards and his team plotted every stone chipping found in the trench. The distribution shows the straight edge where a sarsen once lay while it was being dressed.

Colin has spent a long time, during various visits inside Stonehenge, looking at the minute details of the finished product. Some surfaces of the sarsens have been hammered smooth, while others are speckled with tiny pockmark-like holes. Some stones have wide grooves separated by low ridges. No stone is dressed exactly the same as another.

A closer look also reveals that the inside faces of the stones, in both the outer circle and in the trilithon horseshoe, have been dressed, as have their thin sides, whereas their backs (facing outward) are either unmodified or have been dressed to about head height only. When the sarsens lay in the

dressing zone, the stone-dressers would have been unable to get at the stones’ undersides. The sarsens would have then been brought into the construction area, presumably on wooden sledges or cradles, and each maneuvered to the outside edge of its stonehole before being erected. They would have been raised from the outside of the circle toward the inside, like petals closing on a flower. The back of each stone (on which it had been lying) would have been inaccessible until the stone was raised; final dressing of the back could then be carried out, but only to head height.

This finally explains why the inner faces of the sarsen circle are better dressed than their outer faces, a feature first noted by Stukeley three hundred years ago.

15

It may also help to shed light on the curiously small size of one of the sarsens in the stone circle. Stone 11 stands upright but is not much larger than a lintel. It is far too short to have ever been a support for a continuous line of lintels from Stone 10 to Stone 12. In 2005, Mike Pitts was faced with the dilemma of how to reconstruct its lintels. The television company Channel 5 was building a full-sized replica of Stonehenge in polystyrene. Since Stones 10 and 12 have tenons (knobs that project from the top of the stone to fit the cup-shaped mortise holes of lintels), they were definitely designed to support lintels. A double-length stone lintel bridging the gap over Stone 11 would not have been stable but a wooden substitute might. Mike’s solution was to use a timber lintel over the top of Stone 11.

Looking again at the surfaces of Stone 11, I could see that its inner face never received the same dressing treatment as the other sarsen uprights. Perhaps this little shorty was not part of the main build. Maybe it was added later, taken from one of the stoneholes of the Station Stones or from one of the two stoneholes next to the Slaughter Stone. Perhaps there never were lintels here. Stone 11 lies on the axis of the south entrance to Stonehenge. Maybe the tenons on all the sarsen uprights were shaped in the quarry or the dressing area in a standardized production-line fashion, before anyone realized that the stones in this part of the circle would not need mortise-and-tenon joints. Interestingly, a former bluestone lintel lies close by (now mostly buried below ground)—perhaps this is the remnant of an entrance through the bluestone circle at this point. Only further excavation can reveal whether Stone 11 is part of the original build or a later addition to the sarsen circle.