Stonehenge a New Understanding (54 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Silbury Hill has been excavated twice in modern times, by Atkinson in 1968–1970, and by English Heritage in 2007–2008. It dates to 2490–2340 BCE, broadly contemporary with Stage 3 at Stonehenge.

Just how important Stonehenge remained for the rest of prehistory is debatable. There’s no doubt that people visited it throughout the

following millennia, judging by the shards of pottery from the Bronze Age, Iron Age, and later. Just over a mile to the east, the construction of a hillfort called Vespasian’s Camp (though it has absolutely nothing to do with Claudius’s general Vespasian, who invaded Britain in CE 43) shows that this landscape was occupied and farmed in the Iron Age (750 BC–CE 43). Durrington Walls, too, was being used at this time, being the site of a large agricultural settlement during the Iron Age. This brings us to another disputed interpretation of Stonehenge: that it was internationally renowned during the Iron Age.

In the first century BC, the Roman historian Diodorus Siculus (Diodorus of Sicily) recorded in Book II of his

Library of History

that, on an island in the far north of Europe, in the land of the Hyperboreans, there was a temple where the god Apollo was said to reside during the summer months, returning to his temple at Delphi for the rest of the year. The Hyperborean temple was associated, he said, with the vernal equinox and the Pleiades constellation. He obtained this story from a late-fourth-century BC writer Hecateus of Abdera, who, in turn, had found it in the writings of the Greek seafarer and explorer Pytheas of Marseilles. Diodorus described this building as “a temple of a spherical form,” which has been taken to mean a round temple.

Even if we discount the possibility that Diodorus was referring to one of any number of circular Iron Age wooden structures in Britain or Ireland—and we have no idea how many might still remain to be discovered—the prehistorian Aubrey Burl has highlighted an important reason why this temple could not have been Stonehenge. According to Diodorus, the moon as viewed from the island in question appears closer to the earth.

11

Burl points out that, if this was an attempt to describe a particular astronomical phenomenon, it cannot be a description of southern Britain. Rather, Diodorus may be describing a lunar phenomenon that can only be seen much further north, at 58 degrees north, at least 500 miles from Salisbury Plain. Burl thinks that the temple in question is the Neolithic stone circle at Calanais on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides.

If we discount Diodorus’s story as having nothing to do with Stonehenge, as I think we should, Stonehenge’s first appearance in written records was in CE 1129. In his Historia Anglorum, Henry of Huntingdon, archdeacon of Huntingdon in the diocese of Lincoln,

described Stonehenge as one of four wonders of Britain. Of it, he wrote, “no one has been able to discover by what mechanism such vast masses of stone were elevated, nor for what purpose they were designed.”

12

For nearly nine hundred years, people have puzzled over the same questions. Stonehenge still keeps many of its secrets, but we now know a little more about when, how, and why it was built. Although further excavation at Stonehenge itself is unlikely in the near future, new survey and excavation projects in the area—some already under way—will continue to add to our knowledge in years to come. It seems perverse that Stonehenge has become a focus of conflict and disagreement when the purpose of its construction was to symbolize social unity and cultural cohesion.

__________

Our 2008 excavation of Aubrey Hole 7 recovered the cremated bones of about sixty people buried within Stonehenge more than four thousand years ago.

The 26.6 square kilometers of the Stonehenge World Heritage Site, including Durrington Walls, Stonehenge, and other Neolithic sites. Clusters of Early Bronze Age barrows encircle Stonehenge.

Stonehenge without the tourists.

Sunset through sarsen stones 1 and 30. These form the northeast entrance to Stonehenge, leading to and from the Avenue.

Reconstruction of Stonehenge Stage 1.

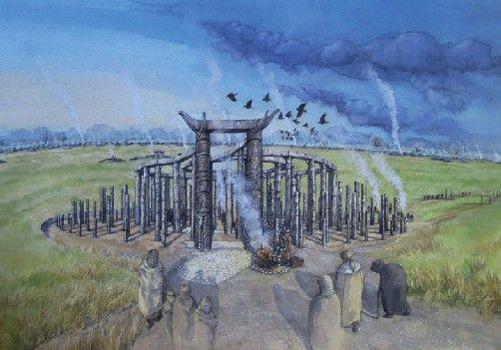

Reconstruction of Stonehenge Stage 3.

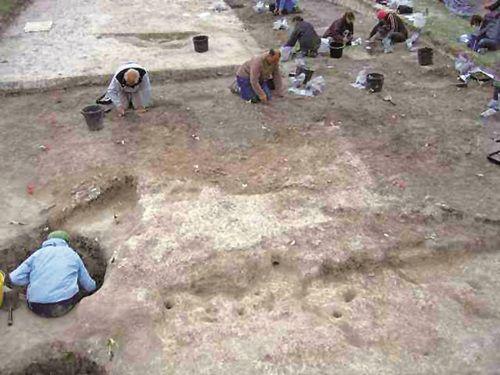

Colin Richards (center top) excavating one of the Neolithic houses at Durrington Walls.

Trenches around the east entrance of Durrington Walls revealed Neolithic houses (foreground) and the avenue running to the river (visible in the far trench).

The Durrington Walls Avenue had a surface of broken flint (darker area in center), flanked by chalk banks.