Stonehenge a New Understanding (53 page)

Read Stonehenge a New Understanding Online

Authors: Mike Parker Pearson

Tags: #Social Science, #Archaeology

Elsewhere in Britain, some monuments were modified. One example of such remodeling is a long barrow at Skendleby in north Lincolnshire, whose ditches were re-dug in this period, many hundreds of years after the barrow was first constructed, and its mound rebuilt.

4

Otherwise, there was no great funerary monument-building. The early Beaker burials were not marked by round barrows; these did not appear until after the start of the Bronze Age, in 2200 BC.

Britain was open to new influences from the Continent. Things were done differently there—no overlords told the people how much earth to move or how many stones to lift. Personal identity was emphasized and expressed through the wearing of ornaments by both men and women. The dead were still treated with ceremony, but in ways that quickly removed them from the living; they were no longer a constant presence. The old regime was in danger of being undermined and, ultimately, it would fall. Rather like Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, the greatest monumental spectacles preceded the regime’s demise. Silbury Hill was that last great monument. After that, no one had the will or ability to work for the authorities on any grand scale.

By 2000 BC the world of Stonehenge had changed. The avenue ditches had been cleaned out and the bluestones rearranged in an outer bluestone circle and an inner bluestone oval. This would be the last time that any stones were moved until stone-robbers came to dismantle the structure. Activities had largely ceased on the other Wessex henges. At Mount Pleasant, however, the henge’s interior was enclosed within a huge palisade wall of timber posts around 2100 BC.

5

Whether the single entrance through this palisade led into a ceremonial space, or whether this was a fortification is unknown. One or more of the West

Kennet palisaded enclosures might also have been occupied around this time.

By now, monument-building had picked up but in a quite different form. From 2200 BC, round barrows started to appear across the landscapes of Britain. Particular concentrations have been noted around the great henges of Wessex, and today more than 350 of these Bronze Age burial mounds are protected within the Stonehenge World Heritage Site alone. Between 2200 and 1500 BC, both sides of the River Avon, in an area centered on Durrington Walls, were covered with more than 1,000 round barrows. The only locations left empty were the “envelope” around Stonehenge (though not entirely so), and the ridge of hills that includes Beacon Hill. Whether these were too sacred to occupy is anyone’s guess.

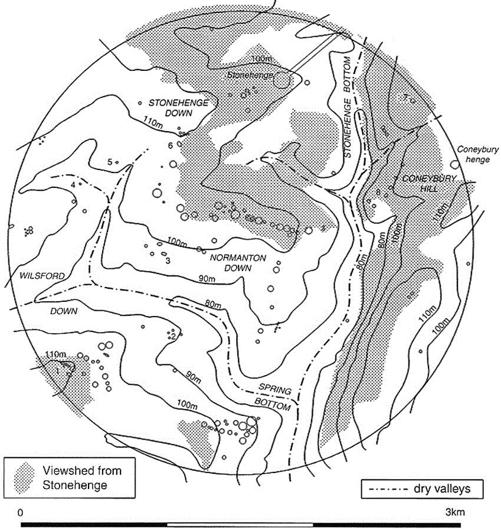

Visible from Stonehenge to its south are the Early Bronze Age round barrows on Normanton Down, including the rich burial under Bush Barrow. A viewshed is those areas of landscape visible from any particular point, in this case Stonehenge.

These round barrows were monuments on a much more personal scale. People were now building only for their own family’s ancestors. To construct an average-sized round barrow would have needed only the labor of the extended family of a small lineage. If any one of us were to assemble all the descendants of one great-grandfather, such a group would be easily big enough to build a round barrow. Even so, the work would have been hard and must have taken months. During one of our excavation seasons, we took a day off to visit a team from Bournemouth University excavating a round barrow near Cranborne Chase. Using a team of around twenty diggers over three summer seasons, their director John Gale has meticulously unpicked the entire

construction sequence.

6

To put it in “rewind” gives us some idea of the scale of the process.

John Gale’s team of Bournemouth University students excavating a round barrow at High Lea Farm, Dorset, in 2008. The central baulk preserves the last remnants of the turf that once formed the mound, capped by chalk from the ditch.

The building of this Cranborne Chase barrow began with the erection of a circular wooden fence around the chosen spot for the grave. Other fences were erected around this in a series of concentric rings. Then the grave was dug out and the cremated bones were buried within a Collared Urn. John Gale has so far found no trace of the site of the funeral pyre itself. The grave was filled in, but some or all of the soil for this was brought from elsewhere, leaving the chalk that originally came from the hole lying around it on the surface.

The hardest job of all then began. Turfs were cut from surrounding grassland, presumably with antler picks, and then piled up to form a mound 30 meters in diameter, centered on the grave. This tedious and difficult labor must have hurt, physically, emotionally, and economically. Perfectly good grassland for the herds was being removed; the area of ground stripped of its turf was thereby taken out of productive use for years afterward. Some of the denuded area could later have been plowed up, but no evidence has been found for this.

Finally, a circular ditch, just over 1.5 meters deep and 30 meters in diameter, was dug around the perimeter of the turf mound. This ditch was deep and wide enough to prevent any casual visitor from climbing on to the barrow, which was now capped with a layer of gleaming white chalk. This reversed world—in which grass lay beneath chalk—was separated from the everyday world by this ditch with no entrances.

Not everybody who died between 2200–1500 BC was buried under a round barrow, though it clearly became the fashionable style for those who had enough land to provide the turf, enough family to provide the labor, and a big enough food surplus to feed the numbers needed to build the mound and dig its ditch. There was a wealth divide, also apparent in the grave goods, and it started widening. By 1900 BC, some burials were lavishly equipped—notably those within the barrow cemetery of Normanton Down, overlooking Stonehenge from the south. The most dramatic of these rich burials is the man buried beneath Bush Barrow.

7

Other men and women buried in nearby barrows were also provided with ornaments of gold, amber, and jet.

Similarly rich graves have been found all over Wessex. In 1938, Stuart Piggott declared them to be the Wessex Culture, a group of aristocratic burials centered on Wessex, but with outliers in East Anglia, and also occurring elsewhere in England, Wales, Scotland, and Brittany.

8

The name has stuck and these barrows appear to have been a first wave of fancy burials. As a result they are known as “Wessex I,” to distinguish them from a later sequence of burials (around 1700–1500 BC) known as “Wessex II.” We have recently obtained the first radiocarbon date for a Wessex I burial, and it confirms the date as being around 1900 BC.

9

By now, Stonehenge’s stones had received their final modification.

We will never know just how much gold was owned by the families burying these individuals in the Wessex I barrows but, given the amounts that they could evidently afford to leave in the ground with the corpse, it is likely to have been a lot. To get an idea of the quantities of gold in circulation by this time, it’s worth visiting the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. Five minutes in the “gold hall,” packed with Bronze Age gold ornaments, is enough to get an impression of the sheer scale of Bronze Age bling.

With no Bronze Age banks or safety-deposit boxes, this jewelery must have been worn more frequently than just on special occasions. These people wanted to show off their wealth. Burying this amount of goldwork with a dead relative was an extraordinarily ostentatious thing to do; the people who arranged these funerals were able to show that they were so rich that they could easily spare large quantities of gold.

Overall, the picture we have of Stonehenge’s decline suggests a gradual process. It appears to have ended not with a bang but with a whimper. Even though the main construction work had finished by the time that the Amesbury Archer and his fellow immigrants arrived in Britain, Stonehenge remained a focus for them, as demonstrated by the hundreds of Beaker pottery shards from in and around the monument. Yet the area in which it stood was now treated very differently. The hitherto empty space on all sides of Stonehenge, especially north of the stone circle and south of the Cursus, started to fill with burials and settlements. Beaker shards from small temporary settlements have been found in many areas around Stonehenge, particularly the enigmatic Beaker-period North Kite enclosure, and further north next to the Fargo bluestone scatter.

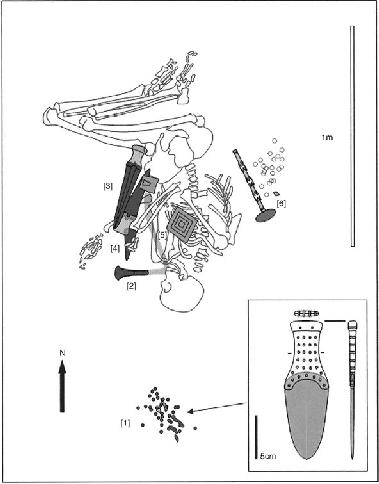

Bush Barrow was excavated by Richard Colt Hoare in 1808. A plan of this Early Bronze Age grave, dating to about 1900 BCE, has been reconstructed by Stuart Needham and colleagues from Hoare’s description of where the many grave goods lay in relation to the skeleton. The objects include bronze studs from the handle of a dagger or knife (1), a bronze ax (2), a pair of bronze daggers and a gold belt buckle (3), a small bronze dagger (4), a gold lozenge (5), and a stone macehead, and its bone and gold fittings (6).

As communal public works projects tailed off in Wessex, ceasing with the construction of Silbury Hill around 2400 BC, Stonehenge was no longer at the center of the people’s world—or, rather, their afterworld. The dead remained just as important as they ever were, except that the

focus was now on family and close kin. By 2000 BC the fashion for monument-building had returned, but it was now channeled toward the family-sized round barrows. Perhaps nobody could recruit the labor any more for building on the scale of Stonehenge or Silbury Hill, or perhaps nobody wanted to. By 1900 BC, there were some very wealthy and powerful families, but their wealth, generated by cattle and other agricultural produce, was directed toward personal adornment and family burial monuments.

By 1500 BC that world too had gone. Southern Britain was parceled up by land boundaries dividing the communal grazing grounds into plots.

10

Intensive arable farming and sedentary farmsteads were now a feature of economic life. Disputes were settled not with bows and arrows but in face-to-face combat using bronze rapiers, leather shields, and body armor. Economically, Wessex was out-matched for soil fertility, and thus cereal production, by the farmlands of eastern England in the lower Thames valley, East Anglia, and the east Midlands. The center of wealth and power shifted, and Stonehenge was left high and dry.