Teutonic Knights (3 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

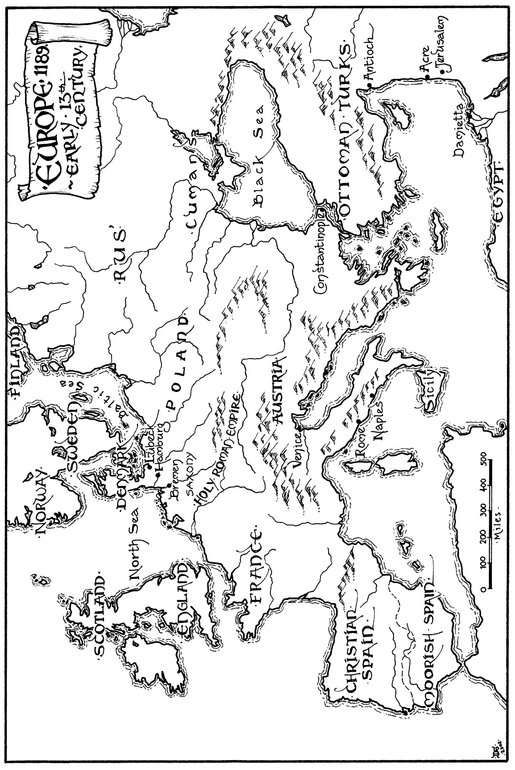

By the mid-eleventh century it was well recognised that enemies of Christianity and Christendom existed outside the Holy Land. Spaniards and Portuguese had no trouble identifying their long struggle against Moslem foes as analogous to the crusades, and soon they had persuaded the Church to offer volunteers similar spiritual benefits as were promised to those who went to defend Jerusalem. Germans and Danes, inspired by St Bernard of Clairvaux, attacked ancient enemies east of the Elbe River. This Wendish Crusade of 1147 overran a bastion of Slavic paganism and piracy and opened the way for eastward migration and expansion.

Poles were soon aware of the potential of employing the crusading spirit in their own eastward and northward expansion. The Prussians, however, were more difficult to defeat than the Wends had been, and they had no leaders who could be persuaded of the benefits of conversion, as the dukes along the southern Baltic coastline in Mecklenburg, Pomerania and Pomerellia had been. Instead, after initial successes in the early thirteenth century, especially in Culm at the bend of the Vistula River, their garrisons fled before the pagan counterattacks.

Technically speaking, the Polish invasions of Prussia were not crusades. They had not been authorised by the popes nor preached throughout Europe by the clergy. But that was a technicality that the Teutonic Knights would correct when, in the late 1220s, Duke Conrad of Masovia and his relatives invited Grand Master Hermann von Salza to send a contingent of his Teutonic Knights to assist in defending Polish lands against Prussian paganism. There was never much thought given to defence, of course. The Poles had planned all along to conquer Prussia. They only needed a little help. Temporarily, they thought.

The Foundation of the Teutonic Order

Germans had expected the Third Crusade (1189 – 91) to be the most glorious triumph that Christian arms had ever achieved. The indomitable red-bearded Hohenstaufen emperor, Friedrich Barbarossa (1152 – 90), had brought his immense army intact across the Balkans and Asia Minor, had smashed the Turkish forces that had blocked the land route east from Constantinople for a century, and had crossed the difficult Cilician mountain passes leading into Syria, whence his forces could pass easily into the Holy Land. There he was expected to lead the combined armies of the Holy Roman Empire, France and England to recover the lost ports on the Mediterranean Sea, opening the way for trade and reinforcements, after which he would lead the Christian host on to the liberation of Jerusalem. Instead, he drowned in a small mountain stream. His vassals dispersed, some hurrying back to Germany because their presence was required at the election of Friedrich’s successor, his son Heinrich VI; others because they anticipated a civil war in which they might lose their lands. Only a few great nobles and prelates honoured their vows by continuing their journey to Acre, which was under siege by crusader armies from France and England.

The newly-arrived Germans suffered terrible agonies from heat and disease in Acre, but their psychological torment may have equalled their physical ailments. Richard the Lionheart (1189 – 99), the English king who was winning immortal fame by feats of valour, hated the Hohenstaufen vassals who had driven his Welf brother-in-law, Heinrich the Lion (1156 – 80), into exile a few years before; and he missed few opportunities to insult or humiliate his supposed allies. Eventually Richard recovered Acre, but he achieved little else. The French king, Phillip Augustus (1180 – 1223), furious at Richard’s repeated insults, went home in anger, and most Germans left too, determined to get revenge on Richard at the first opportunity – as the duke of Austria later did, by turning him over to the new Hohenstaufen emperor for ransom. All German nobles and prelates looked back on this crusading episode with bitter disappointment. Reflecting on the high hopes with which they had set out, they felt that they had been betrayed by everyone – by the English, by the Byzantines, by the Welfs, and by one another. They had but one worthwhile accomplishment to show for all their suffering, or so they thought later: the foundation of the Teutonic Order.

The establishment of the Teutonic Order was an act of desperation – desperation based not on a lack of fighting men, but on ineffective medical care. The crusading army besieging Acre in 1190 had been more than decimated by illness. The soldiers from Northern Europe were not accustomed to the heat, the water, or the food, and the sanitary conditions were completely unsatisfactory. Unable to bury their dead properly, they threw the bodies into the moat opposite the Accursed Tower with the rubble they were using to fill the obstacle. The stink from the corpses hung over the camp like a fog. Once taken by fever, the soldiers died like flies, their agony made worse by the innumerable insects that buzzed around them or swarmed over their bodies. The regular hospital units were overburdened and, moreover, the Hospitallers favoured their own nationals, the French and English (a distinction that few could make easily at the time, since King Richard possessed half of France and lusted after the rest). The Germans were left to their own devices.

The situation was intolerable and it appeared that it would last indefinitely – the siege showed no sign of ending soon, and no German monarch was coming east to demand that his subjects be better cared for by the established hospitals. Consequently some middle-class crusaders from Bremen and Lübeck decided to found a hospital order that would care for the German sick. This initiative was warmly seconded by the most prominent of the German nobles, Duke Friedrich of Hohenstaufen. He wrote to his brother, Heinrich VI, and also won over the patriarch of Jerusalem, the Hospitallers and the Templars to the idea. When they asked Pope Celestine III to approve the new monastic order, he did so quickly. The brothers were to do hospital work like the Hospitallers and to live under the Templar rule. The new foundation was to be named the Order of the Hospital of St Mary of the Germans in Jerusalem. Its shorter, more popular name, the German Order, implied a connection with an older establishment, one practically defunct. Later the members of the order avoided mentioning this possible connection, lest they fall under the control of the Hospitallers, who held supervisory rights over the older German hospital. Nevertheless, the new order does not seem to have discouraged visitors and crusaders from believing that their organisation had a more ancient lineage. Everyone valued tradition and antiquity. Since many religious houses indulged in pious frauds to assert a claim to a more illustrious foundation, it is easy to understand that the members of this new hospital order were tempted to do the same.

In 1197, when the next German crusading army arrived in the Holy Land, it found the hospital flourishing and rendering invaluable service to its fellow-countrymen. Not only did the brothers care for the ill, but they provided hostels for the new arrivals, and money and food for those whose resources had become exhausted, or who had been robbed, or who had lost everything in battle. A significant contingent of the new army came from Bremen, a swiftly growing port city on the North Sea that would soon be a founding member of the Hanseatic League. Those burghers lavished gifts upon the hospital they had helped to establish. As the visitors observed the relatively large number of brothers who had been trained as knights but who had been converted to a religious life while on crusade, they concluded that the hospital order could take on military duties similar to those of the Templars and Hospitallers.

The narrow strip of land that formed the crusader kingdom in the Holy Land was protected by a string of castles, but these were so weakly garrisoned that Christian leaders feared a sudden Turkish onslaught might overrun them before relief could be brought from Europe. The local knights supported by fiefs were far too few for effective defence, and the Italian merchants (the only significant middle-class residents committed to the Western Church) were fully occupied by the need to patrol the sealanes against Moslem piracy or blockade; the most they could do was assist in garrisoning the seaports. Consequently the defence of the country had come to rely on the Templars and the Hospitallers, who had a formidable reputation as cruel and relentless warriors but whose numbers were insufficient to the task after the defeats which had led to the loss of Jerusalem in 1187. Moreover, the two orders frequently quarrelled with one another. The Germans who came to Acre in 1197 decided that their hospital order could provide garrisons for some frontier castles, and they requested Pope Celestine to reincorporate it as a military order. He agreed, issuing a new charter in 1198. The English-speaking world eventually came to call this German order the Teutonic Knights.

3

Technically, the knights in this new military order were friars, not monks. That is, they lived in the world, not in a cloister. But that is merely a technicality, important in their era but hardly significant for ours. What is important is that their organisation was a recognised and respected part of the Roman Catholic Church, under the protection of the popes and with easy access to the papal court. This court, the curia, under papal supervision appointed officers to conduct the final hearings on all disputes involving members of the Church and assigned legates to conduct on-the-spot investigations of significant crises. In practice, of course, the pope and the curia were too busy to inquire closely into the daily practices of religious orders. Although they could react swiftly when reports of irregular practices came to their ears, it was more efficient to require each order to write out its rules and regulations, then periodically review its actual practices against the precepts of its founders.

Because the character of the Teutonic Knights reflected its charter, its rules, its legislation, and that body of laws known as the customs, it is important to look at these documents in detail. They were written down in German so that every member could understand them easily, and they were short and clear, so that they could be easily memorised. Each member took vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience. From the moment the knights entered into the religious life as monks they owned nothing personally; everything was owned in common. In theory they were obliged to tend the sick and thus honour their original purpose for existence. To a certain extent this was compatible with their military duties and their religious devotions, but where it was not such hospital duties were passed on to a special non-noble branch of the membership. The knights attended services at regular intervals throughout the day and night. They were to wear clothes of a ‘priestly colour’ and cover them with a white mantle bearing a black cross that gave them an additional nickname, the Knights of the Cross.

Although there were members who were priests, hospital orderlies, and female nurses, the Hospital of St Mary of the Germans in Jerusalem was primarily a military order. Therefore its membership was largely made up of knights who required horses, weapons, and the equipment of war. Those items had to be maintained personally, so that armour would fit, the swords would be of the right weight and length, and the horse and rider accustomed to one another. Care was taken to avoid acquiring pride in these articles; the rules proscribed gold or silver ornaments or bright colours.

Each knight had to have supporting personnel, usually at a ratio of ten men-at-arms per knight. The men-at-arms were commoners and often members of the order at a lower level. Known as half-brothers, or grey-mantles (from the colour of their surcoats), these took on their duties either for a lengthy period or for life as each chose. They served as squires or sergeants, responsible respectively for providing the knight with a spare horse and new equipment when needed, and for fighting alongside him.

4

The knights had to keep themselves in fighting trim, which would have been a serious problem if they had been strictly cloistered. They were permitted to hunt – an unusual privilege specifically conferred by the papacy – because hunting on horseback was the traditional method of training a knight and had the additional benefit of acquainting him with the local geography. To forbid hunting would have been impractical and also very unpopular among German knights who had grown up amid extensive forests still filled with dangerous beasts and plentiful game. The knights were permitted to hunt wolves, bears, boars, and lions with dogs, if they were doing it of necessity and not just to avoid boredom or for pleasure, and to hunt other beasts without dogs.

The rule warned the knights to avoid women. In the cloister that was no problem, but this was often difficult when travelling or on campaign. At times they had to stay in public hostels or accept hospitality, and it would have been very impolite to turn down a beaker of ale or mead when offered. Moreover, when recruiting members or on diplomatic business they often resided in their host’s castle or villa, because it was impractical to travel on to a neighbouring monastery and thereby miss the banquet, where business was usually conducted on an informal basis. Realising that their duties prevented the knights from living a life of retirement from the world, the rule simply warned them to shun such secular entertainments as weddings and plays, where the sexes mingled, where alcoholic beverages flowed freely into gaudy drinking cups, and where light amusement was all too enticing. They were explicitly warned to avoid speaking to women alone, and, above all, speaking to young women. As for kissing, the usual form of polite greeting among the noble class, they were forbidden to embrace even their mothers and sisters. Female nurses were permitted in the hospitals only when measures were taken to avoid any possibility of scandal.

Punishment for those brothers who violated the rules could be light, moderate, severe, or very severe. Those condemned to a year of punishment, for example, would have to sleep with the servants, wear unmarked clothing, eat bread and water three days of each week, and were deprived of the privilege of holy communion with their knightly brethren. That was a moderate punishment. For more severe infractions there were irons and the dungeons. Once the punishment was served, the culprit could be returned to duty (although barred from holding office in the order) or he could be expelled. For three offences only was there no possibility of forgiveness – cowardice in the face of the enemy, going over to the infidels, and sodomy. For the first two the offender was expelled from the order; for the last he was sentenced to life imprisonment or execution. The most common offences, always minor, were punished by whipping and deprivation of food.