Teutonic Knights (38 page)

Authors: William Urban

Tags: #History, #Non-Fiction, #Medieval, #Germany, #Baltic States

If Sigismund had not been occupied in the south, that would have been the end of Albrecht, but in fact the king had only a small force that he could send to Prussia. This was insufficient to hold the order’s troops in check long. The grand master’s forces ravaged Royal Prussia, reconquered the Neumark, and worried about the appearance of Polish troops. When the Poles came at last, they brought with them Tatars, Bohemian mercenaries, and good artillery; but their numbers were insufficient to capture Albrecht’s fortresses. Nevertheless, the grand master, knowing that all would be lost if a larger enemy force came north, seeing that he now possessed but few subjects who had not been robbed of the means to provide food for his troops and pay taxes, willingly signed a truce at the end of 1520. Schönberg left for Germany, to die in the battle of Pavia (1525), fighting for Emperor Charles V; he was unable to spin a magic web over the emperor as he had Albrecht – Charles V had too many problems already with the Turks, the French, and the Protestants to seek a confrontation with the Polish monarch over the distant and unimportant province of Prussia.

The end of Roman Catholicism in East Prussia came as no surprise. During Albrecht’s 1522 visit to Nuremberg to plead in vain for money from the princes of the Holy Roman Empire, it was clear that he had been visibly affected by Lutheran teachings. In early 1523 Martin Luther had directed one of his major statements ‘to the lords of the Teutonic Knights, that they avoid false chastity’. It was not hard to make inroads among the membership. The knights, and there were fewer of them now, had been reared in a Germany seething with unrest over church corruption. They understood the issues involved in Luther’s protests, and they were unhappy with the lack of morality at the papal curia. Moreover, they understood corruption – Pope Clement VII’s appointment of one absentee bishop to office in Pomerellia and nomination of a relative for the post brought that issue forcefully home. Albrecht, perhaps aware of the public mood and certainly personally concerned about ecclesiastical corruption, took steps to prepare the members of his order for reform proposals: during the Christmas holiday of 1523, while the grand master was still in Germany, he allowed Lutheran preachers to deliver sermons at his court in Königsberg.

This was not hypocrisy. The once brash young prince had learned piety through harsh experience. His youthful sins had led not only him to disaster, but also his innocent subjects. Albrecht had apparently decided to devote the rest of his life to atoning for his early foolishness and indiscretion. Unlike repentant men of an earlier generation, however, he never contemplated withdrawing into a cloister for prayer and penitence. This Renaissance-era prince instead reflected on the choices available to him, and he selected a hard one: the correction of the basic flaw in his order’s status that had condemned Prussia to a century of foreign invasion and civil conflict, its awkward mixture of secular and clerical duties that made it something more than a religious order and something less than a sovereign state.

The grand master quietly sought to discover what response neighbouring princes would make if he followed Luther’s advice, as many northern German bishops were doing, and secularised his Prussian lands. Already during his absence Protestant ministers had carried through the essentials of the Protestant reforms: they had introduced the German language into the worship services, had begun the singing of hymns, and had abolished pilgrimages and the veneration of saints. It was a very practical reform, one based on the general unhappiness with current church conditions but without methodological or theological justifications. Those came later. As the monks, nuns, and priests renounced their vows of celibacy, rumours inevitably began to circulate that the grand master, too, was planning to lay aside his vows, marry, and make himself the head of a secular state. The rumours concentrated on the scandal of the grand master leaving the clerical state and contracting a marriage.

Surprisingly, there was little outrage. The pope and the emperor, of course, warned him against such a course, and his Brandenburg relatives did not approve, but the knights in Prussia and the cities and nobles favoured it decisively and the king of Poland allowed himself to approve it. Secularisation resolved two pressing problems at once: confiscation of the remaining ecclesiastical properties made money available to pay the grand master’s debts, and the way was open to incorporate East Prussia into the Polish kingdom, thereby establishing a peaceful and mutually unthreatening relationship with the monarch. On 10 April 1525, Duke Albrecht took the oath of allegiance in Cracow, a scene immortalised on one of the greatest Polish canvases by the nineteenth-century nationalist painter, Jan Matejko.

East Prussia was not absorbed into the Polish state even to the minimal extent that West Prussia had been. The duke maintained his own army, currency, assembly, and a more or less independent foreign policy. The administrative system changed hardly at all, and the former laws remained in force. A few titles were revised. It was the introduction of Lutheran reforms that had the most profound results.

In 1526 Albrecht entered the ‘true chastity of marriage’ with Dorothea, the eldest daughter of Friedrich of Denmark (1523 – 33). The Danes specialised in providing spouses to the German states along the Baltic; East Prussia completed the collection of regional alliances. This provided Albrecht with a powerful protector and a number of well-placed brothers- and sisters-in-law. Friedrich was also the most important Lutheran ruler of the time.

The uproar in Catholic Germany was as loud and denunciatory as the applause in Protestant Germany, but in Prussia all was quiet. The handful of knights who were too old or unprepared to assume the demands of secular knighthood or who still kept faith with the old belief went to the German master in Mergentheim, who distributed them among his convents and hospitals. Those who remained in Prussia were given fiefs or offices; a few married and founded families, becoming a part of that Junker class for which Brandenburg-Prussia was later famous. However, on the whole, the noble class changed little in its composition. What changed was the nobles’ authority over the serfs, which grew considerably once East Prussia was a secular state. However, the nobles and burghers failed to acquire the political influence they had anticipated obtaining according to the Treaty of Cracow. The Great Peasant Revolt of 1525 was the free farmers’ reaction to rumours that they would be reduced to serfdom by their new lords. Albrecht suppressed the rising easily, but the event undermined the self-confidence of the nobles and gentry so greatly that they looked to the duke for leadership in this and all other matters.

Duke Albrecht of Prussia soon abandoned his efforts to be named a prince of the empire, thus assuring himself of imperial forgiveness and giving him the protection of the Holy Roman Empire against excessive demands by the Polish king in the future. However, Charles V had been too far away, in Spain, or too busy with Luther and the Turks, to give careful consideration to such a minor matter while there was still time. In 1526, however, having seen what happened in East Prussia because he had failed to act, the emperor granted that status to the Livonian master and his possessions. In 1530 Charles named the German master to be the new grand master; henceforth the Teutonic Order was expected to serve the Habsburg dynasty’s political programme.

Royal Prussia was not affected by the secularisation of East Prussia’s government, except, of course, in that Protestant ideas circulated from town to town more easily. Potentially, the people already considered themselves an autonomous German-speaking part of the Polish kingdom with the right to make independent decisions on religion. The townsfolk welcomed both the prospect of peace and the spread of the Lutheran reforms. Not only did the way to a spiritual and cultural reunification of Prussia seem to have opened, but also another means of asserting the authority of the commercial classes and gentry over the ecclesiastical figures who were the nominal rulers of many cities and much of the countryside.

Many who might have objected to the reforms found themselves muted by the even more appalling prospect of the peasant revolt. The rising of peasants here and there in Prussia during 1525 in imitation of the Great Peasant Revolt in Germany was a sobering warning that there were worse changes possible than those associated with cleaning up long-festering problems in the local churches and monasteries. The 1526 uprising in Danzig further demonstrated that unrest had spread to the lower classes in the towns. This was not a time for the upper classes to quarrel over religion – live and let live was the only practical policy.

Albrecht did not consider himself a rebel or disrupter of church unity. Years later he was still continuing his correspondence with Rome and honouring the pope as the head of the Church. The formal separation came later, as one inevitable step of many. The nature of the transformation of Prussia would be easy to exaggerate; in 1525 Protestantism was a reform advocated and welcomed by many devout Roman Catholics who saw no practical alternative. Within a year Sigismund could congratulate himself on his foresight. Louis Jagiellon of Hungary (1516 – 26) fell in the battle of Mohács and the Turks occupied most of his kingdom. The deceased boy king left the remnants of Hungary and his claims to other kingdoms to the Habsburg, Friedrich of Austria, who later became emperor. With Poland now besieged by strong enemies on the east (Moscow), the south (the Turks), and the west (the Habsburgs), it was fortunate that Sigismund had at least relieved himself of worries about the north.

The emperor, meanwhile, had the extensive resources of the Teutonic Order in Germany to use in his wars against the Turks. There would be no distractions by northern affairs. In short, everyone seemed to benefit from the secularisation of the Prussians lands. This assessment was not universal, of course, and anyone who suggested that the Prussian example should be applied to Livonia could count on a hot dispute.

The End in Livonia

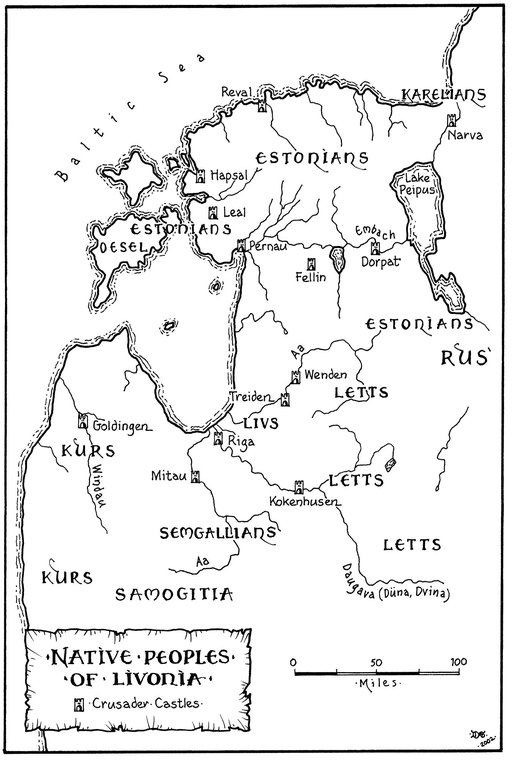

Livonia and Prussia had grown apart during the Thirteen Years’ War. Erlichshausen’s desperate need for money had caused him to look northward, but he succeeded only in provoking the Livonian Knights to limit his authority over them and their lands in every way. By 1473 the Teutonic Knights consisted of three autonomous regions – Prussia, Germany, and Livonia – connected only by a common heritage and occasional common interests. This meant that when wars came to Livonia, the Livonian Order was on its own.

The victories of Wolter von Plettenberg (Livonian master 1494 – 1535) over Ivan III (the Great, 1462 – 1505), the grand duke of Moscow, at the beginning of the 1500s had brought five decades of peace to Livonia. Peace with neighbours, that is. Internal problems were present in abundance. But Wolter managed to keep even those within acceptable bounds, and his influence persisted long after his death at an advanced age in 1535. Unfortunately for his successors, the tide of history was running against them. First and foremost, the Livonian Order no longer governed the region more or less alone, but shared power with the Livonian Confederation, a body which was capable of regulating the coinage, passing common laws for commerce and crime, debating significant issues and unifying public opinion, but lacked an executive branch which could devise an effective foreign policy or unite the region’s military forces under one command. Secondly, the Livonian Order remained a small Roman Catholic organisation in a fiercely Protestant region. Not only were the Scandinavian kingdoms and the duchy of Prussia Lutheran, but so were most of the burghers in the Livonian cities and some of the nobles in the countryside; Protestant offshoots were even strong in Lithuania, and the kings of Poland looked favourably upon the spread of Protestantism in rival lands, assuming more or less correctly that citizens who dared think independently about religion would make trouble for their secular rulers too. Thirdly, several areas formerly important for recruiting knights, especially Lower Saxony and Holstein, were now Protestant; only Westphalia, which had remained Roman Catholic, provided knights for service in the Baltic, and only a few knights could be recruited locally. To a certain degree the insufficiency in recruits was offset by hiring mercenaries. But money had to be raised to pay the mercenaries, and this was best done by increasing grain exports. The question was, how to do this? The answer was to reduce the native population to serfdom and require them to labour on the order’s estates.

38

It is often mistakenly assumed that the crusaders had reduced the native population to serfdom immediately after the conquest in the thirteenth century. In fact, most natives were free taxpayers into the fifteenth century, when a number of developments began the process of changing their status into servitude. Perhaps most important in this social revolution was the natives’ declining usefulness in warfare. As long as hostile armies were penetrating into the country, as was common in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the Livonian master had to rely on the local militias to assist in garrisoning the castles and fighting in pitched battles; but once the Livonian Order managed to build an effective defensive system the militiamen’s function changed, to building fortifications and carting supplies. Next most important was the development of a cash economy. The natives never had much money, and their standard of living was miserably low. Even so, their grain contributions had always been calculated in cash equivalents, payments they often had to borrow to fulfil in years of poor harvests; as they sank into debt, they lost their former protected legal status. In addition, prisoners-of-war were commonly settled on estates as serfs. As the number of free farmers dwindled it was impossible to attract them into border regions whenever Russian or Lithuanian armies carried away the work force. As a result, the owners of the estates tended to replace the lost free peasants with serfs. It is also quite likely that landless sons of free farmers accepted work on the terms of serfs, while retaining their free status; in the course of time these either intermarried with serfs or ‘slipped’ down to their level.

By the early 1550s members of the Livonian Order were openly discussing their options. The one mentioned most often was to convert to Protestantism, divide up the order’s lands among the officers and knights, and make the kinds of reforms in the economy and education that were needed to provide the revenues necessary for national defence. This suggestion brought stalwart Roman Catholic knights almost to apoplexy, causing them to warn direly that this would cost them dearly with the Holy Roman emperor and the electors. Eventually, the decision by the Rigan canons to make a Protestant the assistant and heir of the aged archbishop led to a brief, almost bloodless civil war. The Roman Catholic faction prevailed, more or less, then not long afterward Wilhelm von Fürstenburg became master of the Livonian Order. Most observers interpreted these as Roman Catholic victories, but since the military unpreparedness of the Livonian Confederation had been fully displayed for all neighbours to observe, the triumphs meant little.

39

The problems of Livonia meant little to rulers to the west and south. Denmark and Sweden were too interested in fighting one another to disperse military resources to the east; the king of Poland could never have persuaded his nobles and clerics to authorise spending money to extend his authority to the north – against all evidence they saw the king as a potential tyrant, and they wanted to keep him as weak as practical with the needs of national defence.

The new ruler to the east, however, was of a different mind. Ivan IV (1533 – 84) of Russia was not yet known as ‘the Terrible’, but he was already considered a ruthless monarch with an enormous appetite for more land. Grand duke of Moscow, he took the title of tsar after crushing important Tatar khans to his south and east, thereby expanding his empire almost to the Black Sea; thereafter many Tatars reluctantly served in his armies, while those still beyond his control, mainly in the Crimea, dreamed of defeating him yet and resurrecting the long-lost prestige of the Golden Horde. Ivan had also won over Lithuanian lords from Poland, and he was acquiring new military equipment and expertise as fast as he could find someone to sell it. Later generations of historians would credit him with wanting to conquer the Baltic coastline in order to open trade to the West. More realistically, he just enjoyed taking lands from his neighbours, much as he luxuriated in devising imaginative new ways of humiliating his domestic enemies before murdering them.

Ivan’s method of dividing the Livonian rulers was to combine threats with offers of peace. When the truce negotiated by Wolter von Plettenberg expired, Ivan agreed to renew it only on the condition that the Livonians began to pay ancient taxes and tributes. No living person had ever heard of such taxes and tributes, and certainly the Livonian Order had never paid any. The issue was not so clear in Dorpat, however. There the bishop and the burghers had always stood somewhat aloof, asserting their independence from the Livonian master and even the archbishops of Riga. In the past, they conceded, they had paid some rents to Novgorod and Pskov for swamplands used by beekeepers and hunters, and they might be willing to do so again, if the price was reasonable.

That was all the encouragement Ivan needed to press the point. He offered a bargain. He would settle for an annual payment of 1,000

Talers

and the back taxes, a mere 40,000

Talers

. Since this lump sum was the equivalent of 10,000 oxen, the Livonian ambassadors tried to persuade him to reduce the sum until he finally tired of the game and raided their quarters to seize the moneys they said they had brought with them. But the pleasure he had anticipated would come from handling the coins turned into bitter anger when he learned that the Livonians had not brought a schilling with them.

Neither party had been perfectly honest. The tsar was claiming tribute payments from the twelfth century, before the arrival of the crusaders, and claiming it over regions no Rus’ian prince had ever collected payments from. On the other hand, the Livonians were hoping to evade making any payments at all, expecting that the Holy Roman emperor would declare any treaties they signed null and void. Also, there were indications that the king of Poland, Sigismund Augustus (1548 – 72), might come to the Livonians’ aid. The tsar decided to make a pre-emptive strike, to occupy Livonia while the Polish king was still busy in the south.

In late 1557 the tsar ordered his soldiers and militia to assemble for a long and dangerous winter march to the coast. When the Livonian Confederation received reports that Russian forces had filed out of Moscow, marching through the snow toward the north-west, it ordered a mobilisation.

The campaign was very different from that a half-century earlier. The Livonian cities raised 60,000

Talers

to pay for the cost of a short war, but Master Wilhelm von Fürstenburg decided against meeting the enemy in the field as Wolter von Plettenberg had done. The reputation of the Russian troops and artillery, victors in numerous recent engagements with the Tatars, contrasted too strongly with the unpreparedness of his own forces. The sad performance of the troops and officers in the brief civil war, and the consequent financial crisis, suggested that Livonia was far from ready for a serious fight. The master’s unwillingness to seek a decisive battle precluded the possibility of a short war.

The Germans were numerous enough to fight, if collected in one body and led to war, but the defensive strategy caused them to be scattered; consequently they were outnumbered wherever the Russians chose to attack. The nobles, who formed the main cavalry force, were hesitant to fight pitched battles that would leave their numbers depleted and their families and fiefs without protection. The citizen militias were not trained for field service. The mercenaries wanted to live to spend their wages. Nobody wanted to arm the peasants. In short, the will to fight was lacking, and Fürstenburg was unable to make the members of the Confederation serve against their wishes. The plan adopted was to defend the fortified cities and castles, use the small forces available to harass the invaders, and hope that the Russian supply system would break down during bad weather and cause the tsar to order a retreat. In early 1558 Ivan’s armies marched through the lands of Dorpat without encountering resistance, plundering as they went, then assembled before Narva and began a siege. The Tatar general prevented the German relief army from approaching the city, and on 12 May the Russian artillery opened fire. The defences were strong and might have held firm if an accidental fire had not broken out. Soon the city was burning, and, as the citizens herded their wives and children into the citadel, the Russians stormed the walls. After the sack had ended and the fierce passions of the tsar’s Russian and Tatar troops had cooled, Ivan’s general accepted the surrender of the castle in return for the free withdrawal of the garrison and the people who had taken refuge there. Thus Ivan captured the key to Estonia and trade up the Narva River toward Pskov and Dorpat. With that Ivan IV could have been satisfied, because the Livonians were ready to agree to almost any terms short of surrender, but his appetite was only whetted.

Master Wilhelm called a meeting of his castellans and advocates to discuss the situation. At the end of the meeting the decision was hardly courageous: they sent the tsar 40,000

Talers

as the required tribute. Ivan showed much greater spirit: he sent it back. Then he ordered a march on Dorpat.

The Livonians now began to organise in earnest – much too late. In June of 1558 the estates of the Confederation met in Dorpat to discuss their next steps. They sent to Denmark for help – although King Christian had already said that he could not provide troops; they authorised Reval to blockade Narva against ships trying to trade there; and they asked Sweden for a loan of 200,000

Talers

and mercenaries. Despite their desperation, however, they did not acquiesce to the demand of the Polish monarch that he be given Riga as compensation for his help. In July, however, Dorpat surrendered to Russian besiegers after only token resistance. Since Dorpat should have held out for a considerable time, but didn’t, morale sank everywhere. The delegates to the Confederation wrote to Poland and effectively accepted the royal conditions for providing military assistance. At the same time the Livonian Knights chose Gotthard Kettler, the castellan of Fellin, to ‘share’ Fürstenburg’s duties.