The 30 Day MBA (32 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

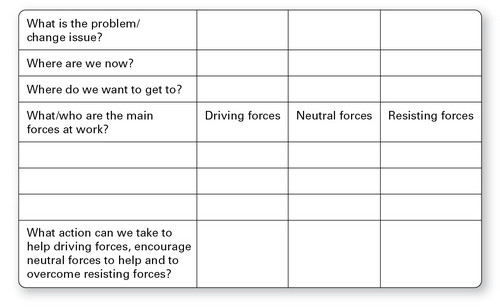

FIGURE 4.13

Â

Force field analysis template

Monitoring staff morale

One way both to identify the need for change and to keep track of progress while implementing changes is to carry out regular surveys of employee attitudes, opinions and feelings. HR-Survey (

www.hr-survey.com

> Employee Opinions) and Custom Insight (

www.custominsight.com

> View Samples > Sample employee satisfaction survey) provide fast, simple and easy-to-use software to carry out and analyse Human Resources surveys. They both have a range of examples of surveys that you can see and try before you buy, which, who knows, might just be enough to stimulate your thinking.

Culture is the defining issue for HR management in international business. A company operating with most of its key employees born, educated and

domiciled in one country or region can reasonably expect to build its HR strategy in terms of recruitment, motivation and management within the scope of a single dominant culture.

Geert Hofstede, a sometime Visiting Professor at INSEAD Business School in Fontainebleau near Paris, France, and a Fellow of the Academy of Management, conducted research with IBM starting in the 1960s, to survey and analyse information about the cultures from some 70 countries. His definition of culture derived from social anthropology and refers to the way people think, feel and act. Hofstede defined it as âthe collective programming of the mind distinguishing the members of one group or category of people from another'. The âcategory' can refer to nations, regions within or across nations, ethnicities, religions, occupations, organizations or genders. A simpler definition he offers is âthe unwritten rules of the social game'. He identified four main dimensions of a nation's culture that the international business person needs to come to grips with to understand culture:

- Power distance: a high power distance ranking indicates a society with inequalities of power and wealth, and where significant upward mobility of its citizens is not possible. A low power distance ranking indicates that the society promotes equality and opportunity for everyone.

- Individualism versus collectivism: a high individualism ranking indicates that individuality and individual rights are paramount within the society, encouraging the forming of a large number of loose relationships. A low individualism ranking typifies societies of a more collectivistic nature, which have close ties between individuals and everyone takes responsibility.

- Uncertainty avoidance: a high uncertainty avoidance ranking indicates that a country has a low tolerance for uncertainty and ambiguity, necessitating a rule-orientated society. A low uncertainty avoidance country is less rule-orientated, more readily accepts change, and takes more and greater risks.

- Masculinity versus femininity: a high masculinity ranking indicates that the country experiences a high degree of gender differentiation, with females being controlled by male domination. A low masculinity ranking indicates that the country has a low level of differentiation and discrimination between genders; females and males are treated equally in society.

Hofstede's scores for his dimension study, a portion of which is shown in

Table 4.1

reveal a clear difference between, say, the United States where individualism is highly rated and Japan where teams are more important. France and the United Kingdom are at opposite ends of the spectrum when it comes to the potential for upward mobility.

TABLE 4.1

Â

Selected country scores for Hofstede's culture dimensions

Country | Power distance | Individualism | Uncertainty | Masculinity |

United States | 40 | 91 | 46 | 62 |

United Kingdom | 35 | 35 | 89 | 66 |

France | 68 | 86 | 71 | 43 |

Japan | 54 | 46 | 92 | 95 |

Hofstede's is not the only system used to get a measure of cultural difference. SH Schwartz who studied at Columbia University has developed the SVI (Schwartz Value Inventory) studying 10 value categories (

http://changingminds.org/explanations/values/schwartz_

inventory.htm

) and Fons Trompenaars teamed with Charles Hampden-Turner to produce their Seven Cultures of Capitalism analysis (

http://changingminds.org/explanations/culture/trompenaars_culture.

htm

). MBAs should have at least a nodding acquaintance with all three of these international culture analysis tools.

Why understanding culture matters

Cultural norms vary greatly from country to country. An American, British or German executive kept cooling their heels waiting for a Spaniard or South American to show up for an appointment may feel irritated. Time matters more to the former group, while the latter may feel completing a discussion more important than the consequences of cutting it short. In the Western world time has a more precise definition than in Arab or Mediterranean cultures.

People accept differences in power in very different ways. In China the meaning has to be inferred or implied while Americans use direct language. It's not that one culture is evasive and the other rude; that's just the way they are. If you are working in the international arena having an appreciation of these differences is vital to successful business relationships.

What determines culture?

Culture is shaped by a number of factors, of which the following are generally accepted as the most important:

- Religion: these are beliefs shared about leading a particular way of life considered to be âgood'.

- Language: both verbal and non-verbal language â facial expressions and hand gestures and the like are a further defining way in which a culture is shaped and groups of people are bound together.

- Education: the extent and depth of a country's education plays its part in cultural development. From an international business perspective the availability of well-educated customers or employees presents important opportunities or challenges.

- The foundations of contract law

- The first business gurus

- Early accounting (and the death penalty!)

- Stock markets and coffee houses

- Limiting liabilities

- Encouraging innovations

- Banking beginnings

- The world's oldest ventures

âM

ay you live in interesting times' â an expression part curse, part exhortation that might have been coined for the years straddling the first and second decades of the 21st century.

As this era looks eerily similar to the world depression triggered in 1929 the philosopher, George Santayana's quote â âthose who cannot learn from history are doomed to repeat it' â is peculiarly appropriate. Henry Ford, the founder of the car company, famously said: âHistory is more or less bunk. It's tradition. We don't want tradition. We want to live in the present and the only history that is worth a tinker's damn is the history we make today.'

There are reasons why an MBA student should acquire a basic appreciation of the milestone events that have led up to the current theories of how organizations, their constituents and their surrounding environments currently operate. The first is much the same reason as why most people learn something of the history of their country, its neighbours, its friends and enemies. Such a study lends interest, context and an appreciation of how we got to where we are today. It is much easier to understand, for example, the enmity between the French and the British with a smattering of information on the Hundred Years' War, the Peninsula War and the

smouldering commercial and territorial disputes that ranged around the world from the Americas to India as well as across the African continent.

The second reason is perhaps even more important. Harvard professor Geoffrey Jones, who edited

The Oxford Handbook of Business History

(2008, Oxford Handbooks in Business & Management) with University of Wisconsin-Madison professor Jonathan Zeitlin, claims in his core history text used at Harvard that: âOver the last few decades, business historians have generated rich empirical data that in some cases confirms and in other cases contradicts many of today's fashionable theories and assumptions by other disciplines. But unless you were a business historian, this data went largely unnoticed, and the consequences were not just academic. This loss of history has resulted in the spread of influential theories based on ill-informed understandings of the past. For example', Jones continues, âcurrent accepted advice is that wealth and growth will come to countries that open their borders to foreign direct investment. The historical evidence shows clearly that this is an article of faith rather than proven by the historical evidence of the past.'

How business history is studied in business schools

If you had taken your MBA before 2000 you would have been unlikely to find business history on the curriculum anywhere outside of the top dozen or so business schools. The subject, however, is fast becoming mainstream. Even comparative newcomers are embracing the subject. Reading Business School, for example, set up its Centre for International Business History (CIBH) in 1997, Cardiff has established an Accounting and Business History Research Group (ABHRG) and the Copenhagen Business School's Centre for Business History, established in 1999, is undertaking a long-term study into the nature and consequences of banking crises. The past few years should give them plenty of material to work on!

Business history as taught in business schools has no single unified body of knowledge in the manner in which, say, accounting, marketing or organizational behaviour has. It would be impossible to study accounting without covering the principles underpinning the key financial reports and how to interpret financial information. While there may well be some unique content in specialized electives, say on Financial Analysis of Mergers, Acquisitions and Other Complex Corporate Restructurings taught at the London Business School, or Dealing with Financial Crime on offer at Cass Business School, the core accounting syllabus in all business schools is near identical â though the way in which it is taught may not be.

History is taught in school and university in eras or themes: the Tudors, the Renaissance, the European World, for example. In one of the premier

UK university history departments nothing much is covered after 1720, while at Harvard Business School nothing much before 1820 is included in the syllabus! At Copenhagen MBA students may have a thorough grasp of Norwegian, Swedish and Danish banking in the interwar years without even a passing reference to the Industrial Revolution, mercantilism or the development of the great family business dynasties. It is just that the subject is too vast to be covered in a meaningful way except by narrowing down the range. Business history is taught eclectically and MBAs swapping notes on their experiences of Business History may find very little in common.

Here, a broad sweep of the subject is taken, providing snapshots of important milestones on matters of enduring significance to business. The content is divided into three eras that are to some extent homogeneous, though the time periods covered in each are very different. The subject starts from 4000

BC

, though the purists would argue that organization and innovation started at least 8,000 years earlier when some communities gave up foraging for farming, adopting fundamentally new tools and techniques for making a living. Unfortunately, little or nothing survives in documented form to make it possible to study such ancient business history. The eras covered range from 3,000 years down to a mere half-century. You are probably aware of the claim that 90 per cent of all the scientists that ever lived are alive today. Well, much the same claim can be made for business innovations. While many important and essential developments occurred many hundreds and even thousands of years ago, the most recent era is the best documented and the most prolific.

The three periods covered are representative samples of some important milestones in business history, selected here as they are the eras least familiar to most students who have at least a passing appreciation of the post Industrial Revolution business world. Although for teaching purposes neat dates are often ascribed to such eras, in practice there is considerable overlap. The Fuggers and the Hanseatic League extended beyond what is commonly regarded as Mediaeval, while patents began their life in that period but didn't have a serious impact until much later.

Babylon and beyond (4000

BC

â1000

AD

)

Two enduring legacies from the ancient business world are the foundations of commercial law and the first efforts at accounting. Both these areas were subject to bursts of rapid development as new ideas took hold. For example, the introduction of coined money in about 600

BC

by the Greeks allowed bankers to keep account books, change and lend money, and even arrange for cash transfers for citizens through affiliate banks in cities thousands of miles away. The Greeks were less interested in accounting as a way to influence business decisions than as a mechanism for citizens to maintain real authority and control over their government's finances. Members of the

Athens Popular Assembly were responsible for controlling receipt and expenditure of public funds and 10 state accountants, chosen by lot, kept them up to the mark.

Although it was not until

AD

1080 that the first law school was established, in Bologna, Italy, and incidentally still in business today, contract law governing transactions and protecting consumer rights had already been around for nearly 4,000 years.

One early example of a family-run business is included here to show that the phenomenon is not peculiar to the Middle Ages and beyond.

Accountancy: single-entry bookkeeping

Sometime before 3000

BC

the people of Uruk and other sister-cities of Mesopotamia began to use pictographic tablets of clay to record economic transactions. The script for the tablets evolved from symbols and provides evidence of an ancient financial system that was growing to accommodate the needs of the Uruk economy. The Mesopotamian equivalent of today's bookkeeper was the scribe. His duties were similar, but even more extensive. In addition to writing up the transactions, he ensured that the agreements complied with the detailed code requirements for commercial transactions. Temples, palaces and private firms employed hundreds of scribes and, much as with the accounting profession today, it was considered a prestigious profession.

In a typical transaction of the time, the parties might seek out the scribe at the gates to the city. They would describe their agreement to the scribe, who would take from his supply a small quantity of specially prepared clay on which to record the transaction.

Governmental bookkeeping in ancient Egypt developed in a fashion similar to the Mesopotamian. The use of papyrus rather than clay tablets allowed more detailed records to be made more easily. And extensive records were kept, particularly for the network of royal storehouses within which the âin kind' tax payments such as sheep or cattle were kept, as coinage had not yet been developed.

Egyptian bookkeepers associated with each storehouse kept meticulous records, which were checked by an elaborate internal verification system. These early accountants had good reason to be honest and accurate, because irregularities disclosed by royal audits were punishable by fine, mutilation or death. Although such records were important, ancient Egyptian accounting never progressed beyond simple list making in its thousands of years of existence. Almost one million accounting records in tablet form currently survive in museum collections around the world.

China, during the Chao Dynasty (1122â256

BC

), used bookkeeping chiefly as a means of evaluating the efficiency of governmental programmes and the civil servants who administered them. A level of sophistication was achieved which was not surpassed in China until after the introduction of the double-entry system a thousand years later.

Accounts in ancient Rome evolved from records traditionally kept by the heads of families, where daily entry of household receipts and payments were kept in an

adversaria

or daybook, and monthly postings were made to a cashbook known as a

codex accepti et expensi

.

Up to mediaeval times, this single-entry system of bookkeeping, divided into two general parts, Income and Outgo, with a statement at the end showing the balance due to the lord of the manner, prevailed in England, as elsewhere. Although these accounts were fairly basic, they were sufficient to handle the needs of the very simple business structures that prevailed. Businessmen operated for the most part on their own account, or in single-venture partnerships that dissolved at the end of a relatively short period of time. This, incidentally, was still the essence of the structure of Lloyd's insurance market into the 21st century. Judging from the uniformity of the way the single-entry bookkeeping was practised, it seems fairly certain that a model was worked out, written up, and widely adopted.

Law: Hammurabi's Code: 1795â1750

BC

Business needs law to determine property rights, without which no meaningful enterprise can take place, and to govern the behaviour and responsibilities of buyers, sellers and others involved in any transaction. The laws that govern business behaviour have evolved over millions of years. The Hammurabi code of laws is the earliest-known example of an entire body of laws, arranged in orderly groups, so that all might read and know what was required of them. The code was carved on a black stone monument, eight feet high, and clearly intended to be in public view. The stone was found in the year 1901, not in Babylon, but in a city of the Persian mountains, to which some later conqueror must have carried it in triumph. The original code now resides in the Louvre Museum in Paris, though much of it has been erased by time.

The code regulates in clear and definite strokes the organization of society in general and commercial dealings in particular. One law states that âif a man builds a house badly, and it falls and kills the owner, the builder is to be slain. If the owner's son was killed, then the builder's son is slain.' Even 4,000 years ago it was considered necessary to protect consumers from shoddy workmanship.

The following laws give evidence of a fairly sophisticated business environment that was well established and prolific enough to require detailed regulation:

- If a merchant entrust money to an agent (broker) for some investment, and the broker suffer a loss in the place to which he goes, he shall make good the capital to the merchant.

- If, while on the journey, an enemy take away from him anything that he had, the broker shall swear by God and be free of obligation. This is a forerunner of the term âforce majeure' which under today's

contract law frees both parties from liabilities and obligations when an extraordinary event beyond their control (war, natural disaster, strike etc) occurs. - If a merchant give an agent corn, wool, oil, or any other goods to transport, the agent shall give a receipt for the amount, and compensate the merchant therefore. Then he shall obtain a receipt from the merchant for the money that he gives the merchant.

- If the agent is careless, and does not take a receipt for the money which he gave the merchant, he cannot consider the un-receipted money as his own.

- If the agent accept money from the merchant, but have a quarrel with the merchant (denying the receipt), then shall the merchant swear before God and witnesses that he has given this money to the agent, and the agent shall pay him three times the sum.

Hammurabi's code was certainly not the earliest. Preceding sets of laws have disappeared, but several traces of them have been found, and Hammurabi's own code clearly implies their existence. He only claimed to be reorganizing a legal system long established.