The 30 Day MBA (37 page)

Authors: Colin Barrow

Despite the competing schools of thought on how business and the economy interact, there is at least general agreement on the most important factors. True, there is much disagreement on how important these factors are and even on how they can be influenced, but on the factors themselves there is a measure of agreement. MBAs will need a grasp of these key issues in order to play a full role in shaping the strategy of their organization.

Economic growth

Government's role in economic policy is generally accepted as being to steer a path that ensures long-term growth without leading to a general rise in prices (see Inflation, below). The underlying belief is that growth in goods and services leads to a happier, more satisfied population, while spreading democracy, diversity, social mobility and greater all-round tolerance. Also, the bigger the gross domestic product (GDP) the more guns and bombs a country can afford, both to defend itself and to impose its will on others who are weaker. There is certainly evidence that people judge their well-being by comparing themselves to others, but unfortunately as income goes up, so do expectations.

There have been many attempts at creating a more comprehensive measure of economic health. Gross National Happiness (

www.grossnationalhappiness.com

) and the Genuine Progress Indicator (

www.rprogress.org/sustainability_indicators/genuine_progress_ indicator.htm

) are attempts to include a range of other factors such as life expectancy, crime rates, pollution, long-term environmental damage, resource depletion and income distribution, for example.

GDP is the yardstick taken to measure the economy, even though that doesn't necessarily say much about the level of happiness in a country. There are a number of ways of comparing GDP both between countries and between time periods and, needless to say, economists can't agree which is best.

Gross domestic product

GDP is the total market value of all final goods and services produced in a country in a one-year period. A country's balance sheet, like that for a business, shows the sources and uses of funds. A country's GDP is usually arrived at using the expenditure method, using the equation GDP = consumption (spending by consumers) + gross investment (spending by business) + government spending + (exports â imports). Each component of expenditure plays a part in helping increase GDP and hence economic growth. (See Keynes above.)

The rate of growth of GDP matters greatly. The UK and Europe's long-run GDP growth rate of around 2.5 per cent will lead to a doubling of the countries' wealth in around three decades. China and India, whose growth rate routinely exceeds 8 per cent, will see average wealth double in less than one decade. All other things being equal, companies looking to set up overseas will head for the countries with rapid growth in GDP.

Gross domestic product per person

Measuring a country's total GDP misses an important consideration â the population. If the growth in both GDP and population were uniform there would be no problem, but that is not the case. Britain's country GDP grew at 2.75 per cent between 2003 and 2007, but as the population grew sharply too, GDP per person grew at a rather slower 2.1 per cent. Japan with its shrinking population also grew its GDP per head by 2.1 per cent, matching that of Britain and beating the United States whose growth measured in this way was only 1.9 per cent as opposed to the 2.9 per cent the United States reported for the economy as a whole.

Gross domestic product at purchasing power parity (PPP)

GDP, usually referred to as nominal GDP, is arrived at by the simple process of adding up expenditure and does not reflect differences in the cost of living in different countries or the currency exchange rate prevailing at the time.

The same amount of GDP, in other words, can buy a lot more goods and services in one country than another. China's GDP per person is about £1,000 nominal but £3,500 at PPP. Calculating PPP is fraught with problems as people buy very different baskets of goods and services. One way round the imperfections is to produce light-hearted attempts at showing PPP using an external product common to most countries.

The Economist

has published a Big Mac Index (BMI) since 1986, with a few variations such the Tall Latte index and a Coca-Cola map that showed the inverse relationship between the amount of Cola consumed per capita in a country and the general standard of health. In 2007, Commonwealth Securities, an Australian bank, created the iPod Index with much the same aim of calculating a proxy for PPP on a country-by-country basis.

Economies tend to follow a cyclical pattern that moves from boom, when demand is strong, to slump, economists' shorthand for a downturn. The death of the cycle has often been claimed as politicians believe they have become better managers of demand, but the âthis time it's different' school of thinking have been proved wrong time and time again.

The cycle itself is caused by the collective behaviour of billions of people â the unfathomable âanimal spirits' of businesses and households. Maynard Keynes (see above) explained animal spirits as: âMost, probably, of our decisions to do something positive, the full consequences of which will be drawn out over many days to come, can only be taken as the result of animal spirits â a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.'

Added to the urge to act is the equally inevitable herd-like behaviour that leads to excessive optimism and pessimism. Charles Mackay (

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

), Joseph De La Vega (

Confusión de Confusiones

) and the more recent

Irrational Exuberance 2nd edition

(Robert J Shiller) between them provide a comprehensive insight into the capacity for collective overreaction. From the tulip mania in 17th-century Holland and the South Sea Bubble (1711â20) to the internet bubble in 1999 and the collapse in US real estate in 2008, the story behind each bubble has been uncomfortably familiar. Strong market demand for some commodity (gold, copper, oil), currency, property or type of share leads the general public to believe that the trend cannot end. Over-optimism leads the public at large to overextend itself in acquiring the object of the mania, while lenders fall over each other to fan the flames. Finally, either the money runs out or groups of investors become cautious. Fear turns to panic selling, so creating a vicious downward spiral that can take years to recover from.

Categories of cycle

Economics is the science, in so far as it can be considered one, of the indistinctly knowable rather than the exactly predictable. Though all cycles, even the one you are in, are difficult to understand or predict with much accuracy, there are discernible patterns and some distinctive characteristics.

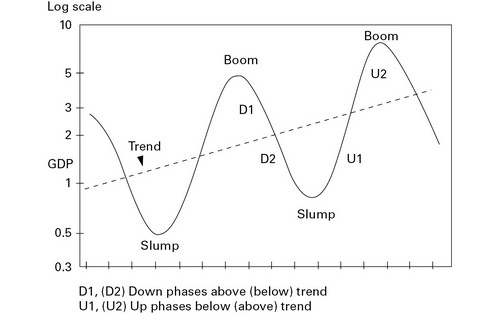

Figure 7.2

shows an elegant curve, which depicts the theoretical textbook cycle.

Four phases typically occur in each textbook cycle:

- U1, where demand is picking up and toeing the line of the long-term trend;

- U2, where demand exceeds the long-term trend;

- D1, where demand dips down to hit the long-term trend;

- D2, where demand slumps below the long-term trend.

FIGURE 7.2

Â

Textbook economic cycle

To make things more complicated, there is not one cycle but at least four that operate, each with different characteristics yet interacting one with the others.

Kondratieff's long waves

Kondratieff (

www.kwaves.com/kond_overview.htm

), a Soviet economist, who fell out with Russia's Marxist leaders and died in one of Stalin's prisons, advanced the theory that the advent of capitalism had created

long-wave economic cycles lasting around 50 years. His theories received a boost when the great depression (1929â33) hit world economies and resonated in Britain in 1980â81 when factory closures, high unemployment and crippling inflation devastated the country. The idea of a long wave is supported by evidence that major enabling technologies, from the first printing press to the internet, take 50 years to yield full value, before themselves being overtaken.

Kuznet's cycle

American economist Simon Kuznet, a Nobel Laureate (1971) working in the University of Pennsylvania, made a lifelong study of economic cycles. He identified a cycle of 15â25 years' duration covering the period it takes to acquire land, get the necessary permissions, build property and sell. Also known as the building cycle, this has credibility as so much of economic life is influenced by property and the related purchases of furniture and associated professional charges, for example for lawyers, architects and surveyors.

Juglar cycle

Clement Juglar, a French economist, studied the rise and fall in interest rates and prices in the 1860s, observing boom and bust waves of 9 to 11 years going through four phases in each cycle: prosperity, where investors piled into new and exciting ventures; crisis, when business failures started to rise; liquidation, when investors pull out of markets; and recession, when the consequences of these failures begin to be felt in the wider economy in terms of job losses and reduced consumption.

Kitchin cycle

In 1923, Joseph Kitchin published in the Harvard University Press an article entitled âReview of Economic Statistics', outlining his discovery of a 40-month cycle resulting from a study of US and UK statistics from 1890 to 1922. He observed a natural cyclical path caused, he believed, by movements in inventories. When demand appears to be stronger than it really is, companies build and carry too much inventory, leading people to overestimate likely future growth. When that higher growth fails to materialize, inventories are reduced, often sharply, so inflicting a âboom, bust' pressure on the economy.

Monitoring cycles

The National Bureau of Economic Research (

www.nber.org

) provides a history of all US business cycle expansions and contractions since 1854. The Foundation for the Study of Cycles (

http://foundationforthestudyofcycles.org

), an international research and educational institution established in 1941 by Harvard economist Edward R Dewey, provides a detailed explanation of different cycles. The Centre for Growth and Business Cycle

Research based at the School of Social Sciences, The University of Manchester (

www.socialsciences.manchester.ac.uk/cgbcr

), provides details of current research, recent publications and downloadable discussion papers on all aspects of business cycles.

CASE STUDY

Robert Wright, a former commercial pilot, started his first business, Connectair, while on the MBA programme at Cranfield. His aim was to start a small feeder airline bringing passengers into the main UK airport hubs such as Heathrow and Gatwick, where they would connect with the major carriers' flights. He started out at the tail-end of the UK recession in 1982, so to keep costs low, as well as being the MD he was at times the pilot, steward and baggage handler as well as greeting passengers at check-in.

Over the next few years he built the business up to the point where it employed 60 people and made a modest profit. He sold it at the height of the Lawson boom in 1989 to Harry Goodman's International Leisure Group, which collapsed spectacularly in the 1991 economic downturn, leaving crippling debts and thousands of people without jobs.

Wright bought the company back for a nominal £1, financing working capital with backing from 3i, the venture capital firm. Over the next eight years he and his team built the business up, now renamed City Flyer Express, selling out in 1999, just ahead of the dotcom stock market collapse, to British Airways for £75 million.

Inflation is defined as too much money chasing too few goods and if it gets out of control it can devastate an economy. Not all goods and services have to experience price increases. The inflation rate itself is measured by defining a basket of goods and services used by a âtypical' consumer and then keeping track of the cost of that basket using such indices as the retail price index. During the upswing stage of a business cycle there is a tendency to overshoot, which can lead to the economy âoverheating'. As there is usually a lag while production struggles to catch up with demand, prices rise to âration' goods and services. Inflation is generally seen being a problem for a number of reasons:

- âInflation makes fools of us all' is a truism about the misleading signals sent by rapid changes in price. Consumers and businesses like certainty, and fluctuating rates of inflation make planning more difficult, which in turns leads to a loss of confidence.

- Inflation redistributes wealth in a haphazard and often unfair manner. For example, savers will find their purchasing power diminish as their fixed sum saved will buy fewer goods and services in the future. Borrowers will benefit as they are effectively paying back a capital sum that is being eroded in value by inflation.

- If the inflation rate is greater than that of other countries, domestic products become less competitive, so exports will be reduced and economic growth will slow.

- High inflation can lead to high wage demands, which can in turn lead to an upward spiral in costs and so feed further inflationary pressures.