The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less (2 page)

Read The 80/20 Principle: The Secret of Achieving More With Less Online

Authors: Richard Koch

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Psychology, #Self Help, #Business, #Philosophy

1

WELCOME TO THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE

For a very long time, the Pareto law [the 80/20 Principle] has lumbered the economic scene like an erratic block on the landscape; an empirical law which nobody can explain.

J

OSEF

S

TEINDL

1

The 80/20 Principle can and should be used by every intelligent person in their daily life, by every organization, and by every social grouping and form of society. It can help individuals and groups achieve much more, with much less effort. The 80/20 Principle can raise personal effectiveness and happiness. It can multiply the profitability of corporations and the effectiveness of any organization. It even holds the key to raising the quality and quantity of public services while cutting their cost. This book, the first ever on the 80/20 Principle,

2

is written from a burning conviction, validated in personal and business experience, that this principle is one of the best ways of dealing with and transcending the pressures of modern life.

WHAT IS THE 80/20 PRINCIPLE?

The 80/20 Principle asserts that a minority of causes, inputs, or effort usually lead to a majority of the results, outputs, or rewards. Taken literally, this means that, for example, 80 percent of what you achieve in your job comes from 20 percent of the time spent. Thus for all practical purposes, four-fifths of the effort—a dominant part of it—is largely irrelevant. This is contrary to what people normally expect.

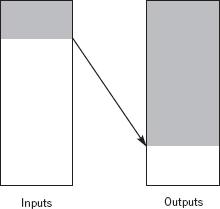

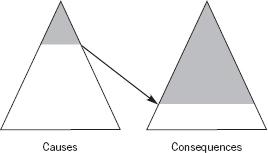

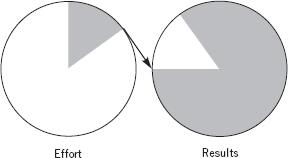

So the 80/20 Principle states that there is an inbuilt imbalance between causes and results, inputs and outputs, and effort and reward. A good benchmark for this imbalance is provided by the 80/20 relationship: a typical pattern will show that 80 percent of outputs result from 20 percent of inputs; that 80 percent of consequences flow from 20 percent of causes; or that 80 percent of results come from 20 percent of effort. Figure 1 shows these typical patterns.

In business, many examples of the 80/20 Principle have been validated. Twenty percent of products usually account for about 80 percent of dollar sales value; so do 20 percent of customers. Twenty percent of products or customers usually also account for about 80 percent of an organization’s profits.

In society, 20 percent of criminals account for 80 percent of the value of all crime. Twenty percent of motorists cause 80 percent of accidents. Twenty percent of those who marry comprise 80 percent of the divorce statistics (those who consistently remarry and redivorce distort the statistics and give a lopsidedly pessimistic impression of the extent of marital fidelity). Twenty percent of children attain 80 percent of educational qualifications available.

In the home, 20 percent of your carpets are likely to get 80 percent of the wear. Twenty percent of your clothes will be worn 80 percent of the time. And if you have an intruder alarm, 80 percent of the false alarms will be set off by 20 percent of the possible causes.

Figure 1 The 80/20 Principle

The internal combustion engine is a great tribute to the 80/20 Principle. Eighty percent of the energy is wasted in combustion and only 20 percent gets to the wheels; this 20 percent of the input generates 100 percent of the output!

3

Pareto’s discovery: systematic and predictable lack of balance

The pattern underlying the 80/20 Principle was discovered in 1897, about 100 years ago, by Italian economist Vilfredo Pareto (1848–1923). His discovery has since been called many names, including the Pareto Principle, the Pareto Law, the 80/20 Rule, the Principle of Least Effort, and the Principle of Imbalance; throughout this book we will call it the 80/20 Principle. By a subterranean process of influence on many important achievers, especially business people, computer enthusiasts and quality engineers, the 80/20 Principle has helped to shape the modern world. Yet it has remained one of the great secrets of our time—and even the select band of cognoscenti who know and use the 80/20 Principle only exploit a tiny proportion of its power.

So what did Vilfredo Pareto discover? He happened to be looking at patterns of wealth and income in nineteenth-century England. He found that most income and wealth went to a minority of the people in his samples. Perhaps there was nothing very surprising in this. But he also discovered two other facts that he thought highly significant. One was that there was a consistent mathematical relationship between the proportion of people (as a percentage of the total relevant population) and the amount of income or wealth that this group enjoyed.

4

To simplify, if 20 percent of the population enjoyed 80 percent of the wealth,

5

then you could reliably predict that 10 percent would have, say, 65 percent of the wealth, and 5 percent would have 50 percent. The key point is not the percentages, but the fact that the distribution of wealth across the population was

predictably unbalanced.

Pareto’s other finding, one that really excited him, was that this pattern of imbalance was repeated consistently whenever he looked at data referring to different time periods or different countries. Whether he looked at England in earlier times, or whatever data were available from other countries in his own time or earlier, he found the same pattern repeating itself, over and over again, with mathematical precision.

Was this a freak coincidence, or something that had great importance for economics and society? Would it work if applied to sets of data relating to things other than wealth or income? Pareto was a terrific innovator, because before him no one had looked at two related sets of data—in this case, the distribution of incomes or wealth, compared to the number of income earners or property owners—and compared percentages between the two sets of data. (Nowadays this method is commonplace and has led to major breakthroughs in business and economics.)

Sadly, although Pareto realized the importance and wide range of his discovery, he was very bad at explaining it. He moved on to a series of fascinating but rambling sociological theories, centering on the role of élites, which were hijacked at the end of his life by Mussolini’s fascists. The significance of the 80/20 Principle lay dormant for a generation. While a few economists, especially in the U.S.,

6

realized its importance, it was not until after the Second World War that two parallel yet completely different pioneers began to make waves with the 80/20 Principle.

1949: Zipf’s Principle of Least Effort

One of these pioneers was the Harvard professor of philology, George K Zipf. In 1949 Zipf discovered the “Principle of Least Effort,” which was actually a rediscovery and elaboration of Pareto’s principle. Zipf’s principle said that resources (people, goods, time, skills, or anything else that is productive) tended to arrange themselves so as to minimize work, so that approximately 20–30 percent of any resource accounted for 70–80 percent of the activity related to that resource.

7

Professor Zipf used population statistics, books, philology, and industrial behavior to show the consistent recurrence of this unbalanced pattern. For example, he analyzed all the Philadelphia marriage licenses granted in 1931 in a 20-block area, demonstrating that 70 percent of the marriages occurred between people who lived within 30 percent of the distance.

Incidentally, Zipf also provided a scientific justification for the messy desk by justifying clutter with another law: frequency of use draws near to us things that are frequently used. Intelligent secretaries have long known that files in frequent use should not be filed!

1951: Juran’s Rule of the Vital Few and the rise of Japan

The other pioneer of the 80/20 Principle was the great quality guru, Romanian-born U.S. engineer Joseph Moses Juran (born 1904), the man behind the Quality Revolution of 1950–90. He made what he alternately called the “Pareto Principle” and the “Rule of the Vital Few” virtually synonymous with the search for high product quality.

In 1924, Juran joined Western Electric, the manufacturing division of Bell Telephone System, starting as a corporate industrial engineer and later setting up as one of the world’s first quality consultants.

His great idea was to use the 80/20 Principle, together with other statistical methods, to root out quality faults and improve the reliability and value of industrial and consumer goods. Juran’s path-breaking

Quality Control Handbook

was first published in 1951 and extolled the 80/20 Principle in very broad terms:

The economist Pareto found that wealth was nonuniformly distributed in the same way [as Juran’s observations about quality losses]. Many other instances can be found—the distribution of crime amongst criminals, the distribution of accidents among hazardous processes, etc. Pareto’s principle of unequal distribution applied to distribution of wealth and to distribution of quality losses.

8

No major U.S. industrialist was interested in Juran’s theories. In 1953 he was invited to Japan to lecture, and met a receptive audience. He stayed on to work with several Japanese corporations, transforming the value and quality of their consumer goods. It was only once the Japanese threat to U.S. industry had become apparent, after 1970, that Juran was taken seriously in the West. He moved back to do for U.S. industry what he had done for the Japanese. The 80/20 Principle was at the heart of this global quality revolution.

From the 1960s to the 1990s: progress from using the 80/20 Principle

IBM was one of the earliest and most successful corporations to spot and use the 80/20 Principle, which helps to explain why most computer systems specialists trained in the 1960s and 1970s are familiar with the idea.

In 1963, IBM discovered that about 80 percent of a computer’s time is spent executing about 20 percent of the operating code. The company immediately rewrote its operating software to make the most-used 20 percent very accessible and user friendly, thus making IBM computers more efficient and faster than competitors’ machines for the majority of applications.

Those who developed the personal computer and its software in the next generation, such as Apple, Lotus, and Microsoft, applied the 80/20 Principle with even more gusto to make their machines cheaper and easier to use for a new generation of customers, including the now celebrated “dummies” who would previously have given computers a very wide berth.