The Act of Creation (13 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

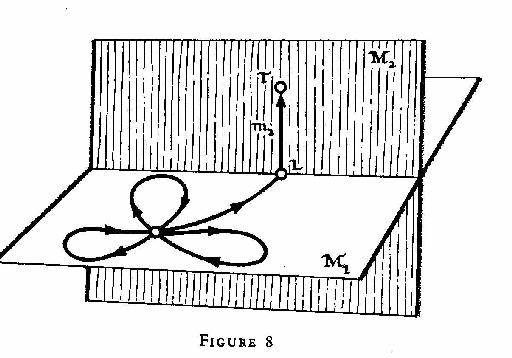

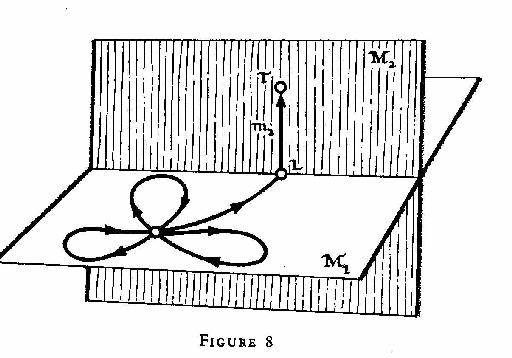

The discovery may now be schematized as follows (Figure 8):

M1

M1

is the same as in the preceding diagram, governed by the

habitual rules of the game, by means of which Archimedes originally tried

to solve the problem;

M2

is the matrix of associations related to

taking a bath; m2 represents the actual train of thought which effects

the connection. The Link

L

may have been a

verbal

concept

(for instance: 'rise of water-level

equals

melting down of my

solid body'); it may equally well have been a

visual

impression in

which the water-level was suddenly seen to correspond to the volume of the

immersed parts of the body and hence to that of the crown -- whose image

was constantly lurking on the fringe of his consciousness. The essential

point is, that at the critical moment

both

matrices

M1

and

M2

were simultaneously active in Archimedes's mind -- though

presumably on different levels of awareness. The creative stress resulting

from the blocked situation had kept the problem on the agenda even while

the beam of consciousness was drifting along quite another plane. Without

this constant pressure, the favourable chance-constellation would have

passed unnoticed -- and joined the legion of man's missed opportunities

for a creative departure from the stale habits of thought which numb

his mental powers.

The sequel to the discovery is well known; because of its picturesque

appeal I shall occasionally refer to discovery in its psychological

aspect as the 'Eureka process' or 'Eureka act'.

Let us look at Archimedes's discovery from a different angle. When one

climbs into a bath one

knows

that the water-level will rise

owing to its displacement by the body, and that there must be as much

water displaced as there is body immersed; moreover, one mechanically

estimates the amount of water to be let into the bath because of this

expectation. Archimedes, too, must have known all this -- but he had

probably never before verbalized, that is, consciously formulated that

bit of knowledge. Yet

implicitly

it was there as part of his

mental equipment; it was, so to speak, included in the code of rules of

bath-taking behaviour. Now we have seen that the rules which govern the

matrix of a skill function on a lower level of awareness than the actual

performance itself -- whether it is playing the piano, carrying on a

conversation, or taking a bath. We have also seen that the bisociative

shock often has the effect of making such implicit rules explicit,

of suddenly focussing awareness on aspects of experience which had

been unverbalized, unconsciously implied, taken for granted; so that a

familiar and unnoticed aspect of a phenomenon -- like the rise of the

water-level -- is suddenly perceived at an unfamiliar and significant

angle. Discovery often means simply the uncovering of something which has

always been there but was hidden from the eye by the blinkers of habit.

This equally applies to the discoveries of the artist who makes us

see familiar objects and events in a strange, new, revealing light

-- as if piercing the cataract which dims our vision. Newton's apple

and Cézanne's apple are discoveries more closely related than

they seem.

Chance and Ripeness

Nearly all of Köhler's chimpanzees sooner or later learned the use

of implements, and also certain methods of making implements. But a dog,

however skilful in carrying a stick or a basket around, will never learn

to use the stick to get a piece of meat placed outside its reach. We

might say that the chimpanzees were

ripe

to discover the use of

tools when a favourable chance-opportunity presented itself -- such as

a stick lying around just when needed. The factors which (among others)

constitute ripeness for this type of discovery are the primates' manual

dexterity and advanced oculo-motor co-ordination, which enable them to

develop the playful habit of pushing objects about with branches and

sticks. Each of the separate skills, whose synthesis constitutes the new

discovery, was well established previously and frequently exercised. In a

similar way Archimedes's mental skill in manipulating abstract concepts

like volume and density, plus his acute powers of observation, even

of trivia, made him 'ripe' for his discovery. In more general terms:

the statistical probability for a relevant discovery to be made is the

greater the more firmly established and well exercised each of the still

separate skills, or thought-matrices, are. This explains a puzzling but

recurrent phenomenon in the history of science: that the same discovery

is made, more or less at the same time, by two or more people; and it may

also help to explain the independent development of the same techniques

and similar styles of art in different cultures.

Ripeness in this sense is, of course, merely a necessary, not a

sufficient, condition of discovery. But it is not quite such an obvious

concept as it might seem. The embittered controversies between different

schools in experimental psychology about the nature of learning and

understanding can be shown to derive to a large extent from a refusal to

take the factor of ripeness seriously. The propounders of Behaviouristic

psychology were wont to set their animals tasks for which they were

biologically ill-fitted, and thus to prove that new skills could be

acquired only through conditioning, chaining of reflexes, learning by

rote. Köhler and the Gestalt school, on the other hand, set their

chimpanzees tasks for which they were ripe or almost ripe, to prove that

all learning was based on insight. The contradictory conclusions at

which they arrived need surprise us no more than the contrast between

the learning achievements of a child of six months and a child of six

years. This is a necessarily over-simplified description (for a detailed

treatment see

Book Two, XII

); the only point

I wish to make is that the more ripe a situation is for the discovery

of a new synthesis, the less need there is for the helping hand of chance.

Archimedes's eyes falling on the smudge in the bath, or the chimpanzee's

eyes falling upon the tree, are chance occurrences of such high

probability that sooner or later they were bound to occur; chance

plays here merely the part of triggering off the fusion between two

matrices by hitting on one among many possible appropriate links. We

may distinguish between the

biological ripeness

ofa species to

form a new adaptive habit or acquire a new skill, and the ripeness of

a

culture

to make and to exploit a new discovery. Hero's steam

engine could obviously be exploited for industrial purposes only at a

stage when the technological and social conditions made it both possible

and desirable. Lastly (or firstly), there is the personal factor --

the role of the creative individual in achieving a synthesis for which

the time is more or less ripe.

The emphasis is on the 'more or less'. If ripeness were all -- as

Shakespeare and the Marxist theory affirm -- the role of genius in

history would be reduced from hero to midwife, who assists the inevitable

birth; and the act of creation would be merely a consummation of the

preordained. But the old controversy whether individuals make or are

made by history acquires a new twist in the more limited field of the

history of science. The twist is provided by the phenomenon of multiple

discoveries. Historical research into this curious subject is of fairly

recent origin; it came as a surprise when, in 1922, Ogburn and Thomas

published some hundred and fifty examples of discoveries and inventions

which were made independently by several persons; and, more recently,

Merton came to the seemingly paradoxical conclusion that 'the pattern

of independent multiple discoveries in science is . . . the dominant

pattern rather than a subsidiary one'. [5] He quotes as an example Lord

Kelvin, whose published papers contain 'at least thirty-two discoveries

of his own which he subsequently found had also been made by others'. The

'others' include some men of genius such as Cavendish and Helmholtz,

but also some lesser lights.

The endless priority disputes which have poisoned the supposedly serene

atmosphere of scientific research throughout the ages, and the unseemly

haste of many scientists to establish priority by rushing into print --

or, at least, depositing manuscripts in sealed envelopes with some learned

society -- point in the same direction. Some -- among them Galileo and

Hooke -- even went to the length of publishing half-completed discoveries

in the form of anagrams, to ensure priority without letting rivals in

on the idea. Köhler's chimpanzees were of a more generous disposition.

Thus one should not underestimate ripeness as a factor facilitating

discoveries which, as the saying goes, are 'in the air' -- meaning,

that the various components which will go into the new synthesis are

all lying around and only waiting for the trigger-action of chance,

or the catalysing action of an exceptional brain, to be assembled and

welded together. If one opportunity is missed, another will occur.

But, on the other hand, although the infinitesimal calculus was developed

independently by Leibniz and by Newton, and a long line of precursors

had paved the way for it, it still required a Newton or a Leibniz to

accomplish the feat; and the greatness of this accomplishment is hardly

diminished by the fact that two among millions, instead of one among

millions, had the exceptional genius to do it. We are concerned with

the question how they did it -- the nature of creative originality --

and not with the undeniable, but trivial consideration that if they had

not lived somebody else would have done it some time; for that leaves

the same question to be answered, to wit, how that someone else did

it. I shall not presume to guess whether outstanding individuals such

as Plato and Aristotle, Jesus of Nazareth and Paul of Tarsus, Aquinas,

Bacon, Marx, Freud, and Einstein, were expendable in the above sense,

so that the history of ideas in their absence would have taken much the

same course -- or whether it is the creative genius who determines the

course of history. I merely wish to point out that some of the major

break-throughs in the history of science represent such dramatic tours

de force, that 'ripeness' seems a very lame explanation, and 'chance'

no explanation at all. Einstein discovered the principle of relativity

'unaided by any observation that had not been available for at least

fifty years before'; [6] the plum was overripe, yet for half a century

nobody came to pluck it. A less obvious example is Everist Galois,

one of the most original mathematicians of all times, who was killed in

an absurd duel in 1832, at the age of twenty. In the night before the

duel he revised a paper to the Académie des Sciences (which had

previously rejected it as unintelligible); then, in a letter to a friend,

he hurriedly put down a number of other mathematical discoveries. 'It

was only after fifteen years, that, with admiration, scientists became

aware of the memoir which the Academy had rejected. It signifies a total

transformation of higher algebra, projecting a full light on what had

been only glimpsed thus far by the greatest mathematicians . . .' [7]

Furthermore, in the letter to his friend, Galois postulated a theorem

which could not have been understood by his contemporaries because

it was based on mathematical principles which were discovered only a

quarter century after his death. 'It must be admitted,' another great

mathematician commented, 'first, that Galois must have conceived these

principles in some way; second, that they must have been unconscious in

his mind since he makes no allusion to them, though they by themselves

represent a significant discovery).' [8]

This leads us to the problem of the part played by unconscious processes

in the Eureka act.

Pythagoras, according to tradition, is supposed to have discovered that

musical pitch depends on the ratio between the length of vibrating

chords -- the starting point of mathematical physics -- by passing

in front of the local blacksmith on his native island of Samos, and

noticing that rods of iron of different lengths gave different sounds

under the blacksmith's hammer. Instead of ascribing it to chance, we

suspect that it was some obscure intuition which made Pythagoras stop

at the blacksmith's shop. But how does that kind of intuition work? Here

is the core ofthe problem of discovery -- both in science and in art.

Logic and Intuition

I shall briefly describe, for the sake of contrast, two celebrated

discoveries of entirely different kinds: the first apparently due to

conscious, logical reasoning aided by chance; the second a classic case

of the intervention of the unconscious.

Eighteen hundred and seventy-nine was the birth-year of immunology --

the prevention of infectious diseases by inoculation. By that time

Louis Pasteur had already shown that cattle fever, rabies, silkworm

disease, and various other afflictions were caused by micro-organisms,

and had firmly established the germ theory of disease. In the spring of

1879 -- he was fifty-seven at that time -- Pasteur was studying chicken

cholera. He had prepared cultures of the bacillus, but for some reason

this work was interrupted, and the cultures remained during the whole

summer unattended in the laboratory. In the early autumn, however,

he resumed his experiments. He injected a number of chickens with the

bacillus, but unexpectedly they became only slightly ill and recovered. He

concluded that the old cultures had been spoilt, and obtained a new

culture of virulent bacilli from chickens afflicted by a current outbreak

of cholera. He also bought a new batch of chickens from the market and

injected both lots, the old and the new, with the fresh culture. The

newly bought chicks all died in due time, but, to his great surprise,

the old chicks, who had been injected once already with the ineffective

culture, all survived. An eye-witness in the lab described the scene

which took place when Pasteur was informed of this curious development. He

remained silent for a minute, then exclaimed as if he had seen a vision:

"Don't you see that these animals have been

vaccinated

!"

Now I must explain that the word 'vaccination' was at that time already

a century old. It is derived from

vacca

, cow. Some time in

the 1760s a young medical student, Edward Jenner, was consulted by a

Gloucester dairymaid who felt out of sorts. Jenner thought that she

might be suffering from smallpox, but she promptly replied: 'I cannot

take the smallpox because I have had the cow-pox.' After nearly twenty

years of struggle against the scepticism and indifference of the medical

profession, Jenner succeeded in proving the popular belief that people

who had once caught the cow-pox were immune against smallpox. Thus

originated 'vaccination' -- the preventive inoculation of human beings

against the dreaded and murderous disease with material taken from the

skin sores of afflicted cattle. Although Jenner realized that cow-pox

and smallpox were essentially the same disease, which became somehow

modified by the organism which carried it, he did not draw any general

conclusions from his discovery. 'Vaccination' soon spread to America and

became a more or less general practice in a number of other countries,

yet it remained limited to smallpox, and the word itself retained its

exclusively bovine connotations.

The vision which Pasteur had seen at that historic moment was, once

again, the discovery of a hidden analogy: the surviving chicks of the

first batch were protected against cholera by their inoculation with the

'spoilt' culture as humans are protected against smallpox by inoculation

with pox bacilli in a modified, bovine form.

Now Pasteur was well acquainted with Jenner's work. To quote one of his

biographers, Dr. Dubos (himself an eminent biologist): 'Soon after the

beginning of his work on infectious diseases, Pasteur became convinced

that something similar to "vaccination" was the best approach to their

control. It was this conviction that made him perceive immediately the

meaning of the accidental experiment with chickens.'

In other words, he was 'ripe' for his discovery, and thus able to pounce

on the first favourable chance that offered itself. As he himself said:

'Fortune favours the prepared mind.' Put in this way, there seems to

be nothing very awe-inspiring in Pasteur's discovery. Yet for about

three-quarters of a century 'vaccination' had been a common practice

in Europe and America; why, then, did nobody before Pasteur hit on

the 'obvious' idea of extending vaccination from smallpox to other

diseases? Why did nobody before him put two and two together? Because,

to answer the question literally, the first 'two' and the second 'two'

appertained to

different frames of reference

. The first was the

technique of vaccination; the second was the hitherto quite separate and

independent research into the world of micro-organisms: fowl-parasites,

silkworm-bacilli, yeasts fermenting in wine-barrels, invisible viruses

in 'the spittle of rabid dogs. Pasteur succeeded in combining these

two separate frames because he had an exceptional grasp of the rules

of both, and was thus prepared for the moment when chance provided an

appropriate link.

He knew -- what Jenner knew not -- that the active agent in Jenner's

'vaccine' was the microbe of the same disease against which the subject

was to be protected, but a microbe which in its bovine host had undergone

some kind of 'attenuation'. And he further realized that the cholera

bacilli left to themselves in the test-tubes during the whole summer had

undergone the same kind of 'attenuation' or weakening, as the pox bacilli

in the cow's body. This led to the surprising, almost poetic, conclusion,

that life inside an abandoned glass tube can have the same debilitating

effect on a bug as life inside a cow. From here on the implications of

the Gloucestershire dairymaid's statement became gloriously obvious:

'As attenuation of the bacillus had occurred spontaneously in some

of his cultures [just as it occurred inside the cow], Pasteur became

convinced

that it should be possible to produce vaccines at will in

the laboratory

. Instead of depending upon the chance of naturally

occurring immunizing agents, as cow-pox was for smallpox, vaccination

could then become a general technique applicable to all infectious

diseases.' [9]

One of the scourges of humanity had been eliminated -- to be replaced in

due time by another. For the story has a sequel with an ironic symbolism,

which, though it does not strictly belong to the subject, I cannot resist

telling. The most famous and dramatic application of Pasteur's discovery

was his anti-rabies vaccine. It was tried for the first time on a young

Alsatian boy by name ofJosef Meister, who had been savagely bitten by

a rabid dog on his hands, legs, and thighs. Since the incubation period

of rabies is a month or more, Pasteur hoped to be able to immunize the

boy against the deadly virus which was already in his body. After twelve

injections with rabies vaccine of increasing strength the boy returned

to his native village without having suffered any ill effects from the

bites. The end of the story is told by Dubos: 'Josef Meister later became

gatekeeper at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. In 1940, fifty-five years

after the accident that gave him a lasting place in medical history,

he committed suicide rather than open Pasteur's burial crypt for the

German invaders.' [9a] He was evidently predestined to become a victim

of one form of rabidness or another.

is the same as in the preceding diagram, governed by the

habitual rules of the game, by means of which Archimedes originally tried

to solve the problem;

M2

is the matrix of associations related to

taking a bath; m2 represents the actual train of thought which effects

the connection. The Link

L

may have been a

verbal

concept

(for instance: 'rise of water-level

equals

melting down of my

solid body'); it may equally well have been a

visual

impression in

which the water-level was suddenly seen to correspond to the volume of the

immersed parts of the body and hence to that of the crown -- whose image

was constantly lurking on the fringe of his consciousness. The essential

point is, that at the critical moment

both

matrices

M1

and

M2

were simultaneously active in Archimedes's mind -- though

presumably on different levels of awareness. The creative stress resulting

from the blocked situation had kept the problem on the agenda even while

the beam of consciousness was drifting along quite another plane. Without

this constant pressure, the favourable chance-constellation would have

passed unnoticed -- and joined the legion of man's missed opportunities

for a creative departure from the stale habits of thought which numb

his mental powers.

The sequel to the discovery is well known; because of its picturesque

appeal I shall occasionally refer to discovery in its psychological

aspect as the 'Eureka process' or 'Eureka act'.

Let us look at Archimedes's discovery from a different angle. When one

climbs into a bath one

knows

that the water-level will rise

owing to its displacement by the body, and that there must be as much

water displaced as there is body immersed; moreover, one mechanically

estimates the amount of water to be let into the bath because of this

expectation. Archimedes, too, must have known all this -- but he had

probably never before verbalized, that is, consciously formulated that

bit of knowledge. Yet

implicitly

it was there as part of his

mental equipment; it was, so to speak, included in the code of rules of

bath-taking behaviour. Now we have seen that the rules which govern the

matrix of a skill function on a lower level of awareness than the actual

performance itself -- whether it is playing the piano, carrying on a

conversation, or taking a bath. We have also seen that the bisociative

shock often has the effect of making such implicit rules explicit,

of suddenly focussing awareness on aspects of experience which had

been unverbalized, unconsciously implied, taken for granted; so that a

familiar and unnoticed aspect of a phenomenon -- like the rise of the

water-level -- is suddenly perceived at an unfamiliar and significant

angle. Discovery often means simply the uncovering of something which has

always been there but was hidden from the eye by the blinkers of habit.

This equally applies to the discoveries of the artist who makes us

see familiar objects and events in a strange, new, revealing light

-- as if piercing the cataract which dims our vision. Newton's apple

and Cézanne's apple are discoveries more closely related than

they seem.

Chance and Ripeness

Nearly all of Köhler's chimpanzees sooner or later learned the use

of implements, and also certain methods of making implements. But a dog,

however skilful in carrying a stick or a basket around, will never learn

to use the stick to get a piece of meat placed outside its reach. We

might say that the chimpanzees were

ripe

to discover the use of

tools when a favourable chance-opportunity presented itself -- such as

a stick lying around just when needed. The factors which (among others)

constitute ripeness for this type of discovery are the primates' manual

dexterity and advanced oculo-motor co-ordination, which enable them to

develop the playful habit of pushing objects about with branches and

sticks. Each of the separate skills, whose synthesis constitutes the new

discovery, was well established previously and frequently exercised. In a

similar way Archimedes's mental skill in manipulating abstract concepts

like volume and density, plus his acute powers of observation, even

of trivia, made him 'ripe' for his discovery. In more general terms:

the statistical probability for a relevant discovery to be made is the

greater the more firmly established and well exercised each of the still

separate skills, or thought-matrices, are. This explains a puzzling but

recurrent phenomenon in the history of science: that the same discovery

is made, more or less at the same time, by two or more people; and it may

also help to explain the independent development of the same techniques

and similar styles of art in different cultures.

Ripeness in this sense is, of course, merely a necessary, not a

sufficient, condition of discovery. But it is not quite such an obvious

concept as it might seem. The embittered controversies between different

schools in experimental psychology about the nature of learning and

understanding can be shown to derive to a large extent from a refusal to

take the factor of ripeness seriously. The propounders of Behaviouristic

psychology were wont to set their animals tasks for which they were

biologically ill-fitted, and thus to prove that new skills could be

acquired only through conditioning, chaining of reflexes, learning by

rote. Köhler and the Gestalt school, on the other hand, set their

chimpanzees tasks for which they were ripe or almost ripe, to prove that

all learning was based on insight. The contradictory conclusions at

which they arrived need surprise us no more than the contrast between

the learning achievements of a child of six months and a child of six

years. This is a necessarily over-simplified description (for a detailed

treatment see

Book Two, XII

); the only point

I wish to make is that the more ripe a situation is for the discovery

of a new synthesis, the less need there is for the helping hand of chance.

Archimedes's eyes falling on the smudge in the bath, or the chimpanzee's

eyes falling upon the tree, are chance occurrences of such high

probability that sooner or later they were bound to occur; chance

plays here merely the part of triggering off the fusion between two

matrices by hitting on one among many possible appropriate links. We

may distinguish between the

biological ripeness

ofa species to

form a new adaptive habit or acquire a new skill, and the ripeness of

a

culture

to make and to exploit a new discovery. Hero's steam

engine could obviously be exploited for industrial purposes only at a

stage when the technological and social conditions made it both possible

and desirable. Lastly (or firstly), there is the personal factor --

the role of the creative individual in achieving a synthesis for which

the time is more or less ripe.

The emphasis is on the 'more or less'. If ripeness were all -- as

Shakespeare and the Marxist theory affirm -- the role of genius in

history would be reduced from hero to midwife, who assists the inevitable

birth; and the act of creation would be merely a consummation of the

preordained. But the old controversy whether individuals make or are

made by history acquires a new twist in the more limited field of the

history of science. The twist is provided by the phenomenon of multiple

discoveries. Historical research into this curious subject is of fairly

recent origin; it came as a surprise when, in 1922, Ogburn and Thomas

published some hundred and fifty examples of discoveries and inventions

which were made independently by several persons; and, more recently,

Merton came to the seemingly paradoxical conclusion that 'the pattern

of independent multiple discoveries in science is . . . the dominant

pattern rather than a subsidiary one'. [5] He quotes as an example Lord

Kelvin, whose published papers contain 'at least thirty-two discoveries

of his own which he subsequently found had also been made by others'. The

'others' include some men of genius such as Cavendish and Helmholtz,

but also some lesser lights.

The endless priority disputes which have poisoned the supposedly serene

atmosphere of scientific research throughout the ages, and the unseemly

haste of many scientists to establish priority by rushing into print --

or, at least, depositing manuscripts in sealed envelopes with some learned

society -- point in the same direction. Some -- among them Galileo and

Hooke -- even went to the length of publishing half-completed discoveries

in the form of anagrams, to ensure priority without letting rivals in

on the idea. Köhler's chimpanzees were of a more generous disposition.

Thus one should not underestimate ripeness as a factor facilitating

discoveries which, as the saying goes, are 'in the air' -- meaning,

that the various components which will go into the new synthesis are

all lying around and only waiting for the trigger-action of chance,

or the catalysing action of an exceptional brain, to be assembled and

welded together. If one opportunity is missed, another will occur.

But, on the other hand, although the infinitesimal calculus was developed

independently by Leibniz and by Newton, and a long line of precursors

had paved the way for it, it still required a Newton or a Leibniz to

accomplish the feat; and the greatness of this accomplishment is hardly

diminished by the fact that two among millions, instead of one among

millions, had the exceptional genius to do it. We are concerned with

the question how they did it -- the nature of creative originality --

and not with the undeniable, but trivial consideration that if they had

not lived somebody else would have done it some time; for that leaves

the same question to be answered, to wit, how that someone else did

it. I shall not presume to guess whether outstanding individuals such

as Plato and Aristotle, Jesus of Nazareth and Paul of Tarsus, Aquinas,

Bacon, Marx, Freud, and Einstein, were expendable in the above sense,

so that the history of ideas in their absence would have taken much the

same course -- or whether it is the creative genius who determines the

course of history. I merely wish to point out that some of the major

break-throughs in the history of science represent such dramatic tours

de force, that 'ripeness' seems a very lame explanation, and 'chance'

no explanation at all. Einstein discovered the principle of relativity

'unaided by any observation that had not been available for at least

fifty years before'; [6] the plum was overripe, yet for half a century

nobody came to pluck it. A less obvious example is Everist Galois,

one of the most original mathematicians of all times, who was killed in

an absurd duel in 1832, at the age of twenty. In the night before the

duel he revised a paper to the Académie des Sciences (which had

previously rejected it as unintelligible); then, in a letter to a friend,

he hurriedly put down a number of other mathematical discoveries. 'It

was only after fifteen years, that, with admiration, scientists became

aware of the memoir which the Academy had rejected. It signifies a total

transformation of higher algebra, projecting a full light on what had

been only glimpsed thus far by the greatest mathematicians . . .' [7]

Furthermore, in the letter to his friend, Galois postulated a theorem

which could not have been understood by his contemporaries because

it was based on mathematical principles which were discovered only a

quarter century after his death. 'It must be admitted,' another great

mathematician commented, 'first, that Galois must have conceived these

principles in some way; second, that they must have been unconscious in

his mind since he makes no allusion to them, though they by themselves

represent a significant discovery).' [8]

This leads us to the problem of the part played by unconscious processes

in the Eureka act.

Pythagoras, according to tradition, is supposed to have discovered that

musical pitch depends on the ratio between the length of vibrating

chords -- the starting point of mathematical physics -- by passing

in front of the local blacksmith on his native island of Samos, and

noticing that rods of iron of different lengths gave different sounds

under the blacksmith's hammer. Instead of ascribing it to chance, we

suspect that it was some obscure intuition which made Pythagoras stop

at the blacksmith's shop. But how does that kind of intuition work? Here

is the core ofthe problem of discovery -- both in science and in art.

Logic and Intuition

I shall briefly describe, for the sake of contrast, two celebrated

discoveries of entirely different kinds: the first apparently due to

conscious, logical reasoning aided by chance; the second a classic case

of the intervention of the unconscious.

Eighteen hundred and seventy-nine was the birth-year of immunology --

the prevention of infectious diseases by inoculation. By that time

Louis Pasteur had already shown that cattle fever, rabies, silkworm

disease, and various other afflictions were caused by micro-organisms,

and had firmly established the germ theory of disease. In the spring of

1879 -- he was fifty-seven at that time -- Pasteur was studying chicken

cholera. He had prepared cultures of the bacillus, but for some reason

this work was interrupted, and the cultures remained during the whole

summer unattended in the laboratory. In the early autumn, however,

he resumed his experiments. He injected a number of chickens with the

bacillus, but unexpectedly they became only slightly ill and recovered. He

concluded that the old cultures had been spoilt, and obtained a new

culture of virulent bacilli from chickens afflicted by a current outbreak

of cholera. He also bought a new batch of chickens from the market and

injected both lots, the old and the new, with the fresh culture. The

newly bought chicks all died in due time, but, to his great surprise,

the old chicks, who had been injected once already with the ineffective

culture, all survived. An eye-witness in the lab described the scene

which took place when Pasteur was informed of this curious development. He

remained silent for a minute, then exclaimed as if he had seen a vision:

"Don't you see that these animals have been

vaccinated

!"

Now I must explain that the word 'vaccination' was at that time already

a century old. It is derived from

vacca

, cow. Some time in

the 1760s a young medical student, Edward Jenner, was consulted by a

Gloucester dairymaid who felt out of sorts. Jenner thought that she

might be suffering from smallpox, but she promptly replied: 'I cannot

take the smallpox because I have had the cow-pox.' After nearly twenty

years of struggle against the scepticism and indifference of the medical

profession, Jenner succeeded in proving the popular belief that people

who had once caught the cow-pox were immune against smallpox. Thus

originated 'vaccination' -- the preventive inoculation of human beings

against the dreaded and murderous disease with material taken from the

skin sores of afflicted cattle. Although Jenner realized that cow-pox

and smallpox were essentially the same disease, which became somehow

modified by the organism which carried it, he did not draw any general

conclusions from his discovery. 'Vaccination' soon spread to America and

became a more or less general practice in a number of other countries,

yet it remained limited to smallpox, and the word itself retained its

exclusively bovine connotations.

The vision which Pasteur had seen at that historic moment was, once

again, the discovery of a hidden analogy: the surviving chicks of the

first batch were protected against cholera by their inoculation with the

'spoilt' culture as humans are protected against smallpox by inoculation

with pox bacilli in a modified, bovine form.

Now Pasteur was well acquainted with Jenner's work. To quote one of his

biographers, Dr. Dubos (himself an eminent biologist): 'Soon after the

beginning of his work on infectious diseases, Pasteur became convinced

that something similar to "vaccination" was the best approach to their

control. It was this conviction that made him perceive immediately the

meaning of the accidental experiment with chickens.'

In other words, he was 'ripe' for his discovery, and thus able to pounce

on the first favourable chance that offered itself. As he himself said:

'Fortune favours the prepared mind.' Put in this way, there seems to

be nothing very awe-inspiring in Pasteur's discovery. Yet for about

three-quarters of a century 'vaccination' had been a common practice

in Europe and America; why, then, did nobody before Pasteur hit on

the 'obvious' idea of extending vaccination from smallpox to other

diseases? Why did nobody before him put two and two together? Because,

to answer the question literally, the first 'two' and the second 'two'

appertained to

different frames of reference

. The first was the

technique of vaccination; the second was the hitherto quite separate and

independent research into the world of micro-organisms: fowl-parasites,

silkworm-bacilli, yeasts fermenting in wine-barrels, invisible viruses

in 'the spittle of rabid dogs. Pasteur succeeded in combining these

two separate frames because he had an exceptional grasp of the rules

of both, and was thus prepared for the moment when chance provided an

appropriate link.

He knew -- what Jenner knew not -- that the active agent in Jenner's

'vaccine' was the microbe of the same disease against which the subject

was to be protected, but a microbe which in its bovine host had undergone

some kind of 'attenuation'. And he further realized that the cholera

bacilli left to themselves in the test-tubes during the whole summer had

undergone the same kind of 'attenuation' or weakening, as the pox bacilli

in the cow's body. This led to the surprising, almost poetic, conclusion,

that life inside an abandoned glass tube can have the same debilitating

effect on a bug as life inside a cow. From here on the implications of

the Gloucestershire dairymaid's statement became gloriously obvious:

'As attenuation of the bacillus had occurred spontaneously in some

of his cultures [just as it occurred inside the cow], Pasteur became

convinced

that it should be possible to produce vaccines at will in

the laboratory

. Instead of depending upon the chance of naturally

occurring immunizing agents, as cow-pox was for smallpox, vaccination

could then become a general technique applicable to all infectious

diseases.' [9]

One of the scourges of humanity had been eliminated -- to be replaced in

due time by another. For the story has a sequel with an ironic symbolism,

which, though it does not strictly belong to the subject, I cannot resist

telling. The most famous and dramatic application of Pasteur's discovery

was his anti-rabies vaccine. It was tried for the first time on a young

Alsatian boy by name ofJosef Meister, who had been savagely bitten by

a rabid dog on his hands, legs, and thighs. Since the incubation period

of rabies is a month or more, Pasteur hoped to be able to immunize the

boy against the deadly virus which was already in his body. After twelve

injections with rabies vaccine of increasing strength the boy returned

to his native village without having suffered any ill effects from the

bites. The end of the story is told by Dubos: 'Josef Meister later became

gatekeeper at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. In 1940, fifty-five years

after the accident that gave him a lasting place in medical history,

he committed suicide rather than open Pasteur's burial crypt for the

German invaders.' [9a] He was evidently predestined to become a victim

of one form of rabidness or another.

Other books

Fearless Hope: A Novel by Serena B. Miller

First Comes The One Who Wanders by Lynette S. Jones

The Beautiful Child by Emma Tennant

The Jazz Palace by Mary Morris

Treachery in Death by J. D. Robb

Viking Boy by Tony Bradman

The Billionaire's Baby (Key to My Heart Book 3) by Cari, Ella

Zombie Nation by David Wellington

Secret For Vinhelm - The Prequel: A Rock Star Romance by Marcelo, L.

Made To Love Her by Z.L. Arkadie