The Arithmetic of Life and Death (14 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

The Duke of Pork

“A billion here, a billion there, and pretty soon you’re talking about real money.”

—EVERETT DIRKSEN

L

ight travels at about 186,282 miles per second, so it should have taken about 0.015 seconds for news of Reginald DeNiall’s election to the House of Representatives to travel 2,788 miles from Seattle to the nation’s capital. Somehow, though, it seemed like the news got there even faster than that, possibly because of the sincere admiration so many of Reginald’s new peers had for the creative way in which he had managed the final days of his campaign.

This admiration became a matter of serendipity a few weeks later when Reginald was invited to dinner at the Washington, D.C., home of one of the most powerful men in Congress, who was nicknamed the “Gentleman from the South.” That evening, over fried chicken, corn bread, sweet potatoes, black-eyed peas, and homemade biscuits, the Gentleman offered Reginald the opportunity to

represent his party on the powerful House Ways and Means Committee.

This was an unexpected honor for a rookie congressman. The honor had a price. It was that Reginald would vigorously support his host’s campaign for reelection some eighteen months hence.

Reginald, who had generally taken to Capitol politics like a young vulture takes to fresh carrion, intuitively understood what his new benefactor wanted. It wasn’t votes, which hadn’t won an election of consequence since 1960. It was leverage in his district, which meant money. Reginald guessed that his host wanted a lot of it, so he asked how much. Over bread pudding with vanilla sauce, he was answered with a quotation attributed to the late Senator Dirksen of Illinois.

For a lesser man, this might have seemed an impossible task. The Gentleman’s home state was not particularly wealthy, and he had less than a 25 percent approval rating in the rest of the United States, so large, “indirect” campaign contributions were out of the question. Reginald, however, was a businessman who believed in the power of capitalism, so he did his homework, or rather his staff did. A few weeks later, Reginald proposed a business solution to the problem, one that was faithfully implemented by the Gentleman from the South shortly thereafter.

In the very next federal budget, which was passed by his party’s majority in both the House and the Senate, a major aerospace manufacturer in the Gentleman’s home state received an unexpected appropriation for $1 billion in military transport aircraft. No other company could build those airplanes, so jobs were created, property prices were increased,

and businessmen were enriched. In addition, since procurement of those same aircraft had not been requested by the U.S. Air Force in nearly a decade, there was no question about who was really responsible for both the budget line item and the contract award.

Better yet, the cost of the airplanes was not borne solely by taxpayers in the Congressman’s district. Instead, it was shared equally by 139 million taxpayers across the country. Therefore, even though only one in four voters approved of the Gentleman from Georgia outside of his home state, each and every American taxpayer was required to contribute more than seven dollars to his next campaign for reelection.

Since those aircraft will remain in service for many more years, it can be expected that the long-term cost of parts and maintenance will eclipse the original manufacturing price. This means that the American people will eventually be taxed more than two billion dollars, which is a tax assessment of more than $14 per taxpayer, to preserve the congressman’s position, which paid approximately $136,600 per annum (at the time).

Since two billion dollars is more than 14,000 times larger than $136,000, paying that much to preserve a single congressman’s job might not seem entirely sensible. But, to an up-and-coming political entrepreneur like Reginald DeNiall, the capital’s newly crowned “Duke of Pork,” it smelled of opportunity.

Maybe Reginald is on to something. If the deficit is not a concern, as so many Congressmen selflessly contend, then perhaps we should consider extending the principles of pork to the entirety of Congress. Since senators only run

for reelection every sixth year, we could subsidize their reelection campaigns to the tune of a billion dollars each at an annualized cost of only $16.7 billion or so.

There are 435 Representatives in the House and they run for reelection every two years. Therefore, the annualized cost of extending “The Reginald Plan” to them would be around $217.5 billion. The total congressional pork tab would add up to just $234.2 billion dollars per year, or about $1,685 dollars per taxpayer per year.

Of course, besides being somewhat costly when extended to the fullness of Congress, that one billion dollar reelection subsidy could provide each incumbent with an overwhelming advantage. Certainly, it would be impossible for all but a handful of very rich challengers to raise even a tenth of that in campaign contributions. Thus, the continued existence of pork barrel spending, even for an influential few, may eloquently explain why the president of the United States does not have the line item veto and, in some part, why the U.S. government carries the largest debt ever known to mankind.

22

The National Debt

“Politics is the distance between what makes sense and what gets done.”

— JULIAN DATE

A

s of mid-1998, the United States, which means us, had a national debt of about 5.54 trillion dollars. In real numbers that is $5,540,000,000,000. Most folks, maybe even a congressman or two, believe that to be a fairly large sum of money.

The 5.54 trillion-dollar national debt is how much money the U.S. government has had to borrow over the years because it has spent more than it has collected in taxes. The U.S. government borrows money by selling bonds—mostly treasury bonds, treasury bills, and savings bonds—to anyone who will buy them (foreign investors own about 25 percent). In return for lending Uncle Sam the money, the bondholders are entitled to receive interest on the loan.

In 1997, the interest on the national debt was about

$356,000,000,000. That means the U.S. government paid more for interest on its outstanding loans than it paid for defense, or education, or welfare, or medicare, or anything else.

Of course, the U.S. government doesn’t really pay the interest on the national debt. U.S. taxpayers pay it. In 1997, the interest bill alone was more than $2,500 for each and every taxpaying citizen. That is almost $50 per taxpayer per week, just for interest on the federal government’s accumulated debt.

Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough. For the twenty-ninth consecutive year, the U.S. government did not take in enough in taxes to conduct its affairs and pay all of that interest. So again in 1997, the U.S. government had to borrow more money. That is called the deficit. According to the U.S. Bureau of Public Debt, the deficit was only $188 billion in 1997, the lowest figure in many years. (From September 1989 through September 1992, the last Republican administration before President Clinton, the national debt climbed from $2.86 trillion to $4.41 trillion, an average annual deficit of more than $388 billion per year.)

Luckily, the Democrats and the Republicans managed to balance the budget in 1998—or, more accurately, they allowed the strength of the economy to balance the budget without congressional interference. Lest you get too excited, this only means that the annual deficit was eliminated for one consecutive year (although 1999 also looks promising).

However, balancing the budget does not mean that the national debt has been paid back. It’s still there. It’s just not getting bigger anymore. But if the national debt is never paid back, then the interest on the debt will have to

be paid forever. Even for sea turtles, forever is a fairly long time. In fact, unless the U.S. government can find a way to spend less money than it takes in, which means an annual budget surplus, then the interest bill on the national debt will be infinitely large.

For instance, if the national debt stabilizes at 5.5 trillion dollars and the government can continue to borrow money at a steady 6 percent interest, then the interest on the national debt will average around $330,000,000,000 per year. Over the next fifty years, that is a total interest bill of $16.5 trillion, three times the size of the national debt itself. Yet the national debt will remain at a steady $5.5 trillion.

If the national debt remains flat, however, then the amount of money each citizen will have to pay each year will go down. That is because the U.S. population is growing—at a rate of about one person every sixteen seconds (one birth every eight seconds, one death every thirteen seconds, one new immigrant every forty-three seconds, plus adjustments for migration). That is a net increase in population of about 5,400 people per day, or just under two million per year. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates, in fact, that U.S. population will reach 322 million by the year 2020. If the national debt is still $5,540,000,000,000, then the average citizen’s debt load will be about $17,200, a 16 percent improvement over the $20,500 or so that each citizen owes today.

Inflation will also help. At an average of 5 percent inflation, the value of a 1999 dollar will drop to about 34 cents in the year 2020. So the discounted value of each citizen’s national debt load could be as low as $5,850, a whopping 71 percent improvement over the current situation.

That, in fact, appears to be The Plan. On paper it looks

workable. But more things can go wrong. If the national debt increases to ten trillion dollars by the year 2020, which is less than 3 percent annual growth, the average annual interest rate increases to only 8 percent, then the government’s yearly interest bill will jump to about $800,000,000,000. For those of you who find that worrisome, that is only about $2.2 billion per day, including weekends. If it happens, then the nation’s 161 million taxpaying citizens will have to pay an average of $4,969 in interest alone that year, which is more than $95 per taxpayer per week (compared to a cost of around $50 per taxpayer per week in 1997).

In fact, the national debt is already so large that it will not be paid off in the lifetime of any taxpayer reading this book. This means that we will all be paying interest on it every day for the rest of our taxpaying lives. All of us. The only question is whether the same will be true for our grandchildren, their children, and their children.

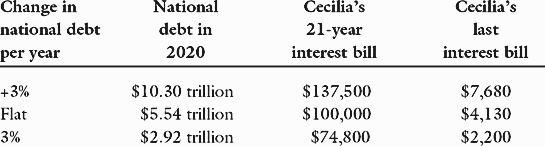

Cecilia Sharpe does not expect to be able to retire until the year 2020. Between now and then, she expects to pay about twice as much tax as the U.S. average. Even if the national debt remains level at $5.54 trillion dollars until then, and even if the taxpayer base grows to 161 million, then Cecilia is forecast to pay more than $100,000 in interest on the national debt before she retires. By herself.

If the deficit returns to a growth rate of just 3 percent of the national debt per year, then the national debt will grow to more than $10 billion by the year 2020. Between now and then, Cecilia will have to pay more than $137,500 in interest on the national debt. In the year 2020 alone, she will pay more than $7,600. By herself.

However, if the national debt is reduced by a mere 3 percent per year starting in the year 2000, then it will drop to a relatively paltry $2.92 trillion by the year 2020. Between now and then, Cecilia will still pay almost $75,000 in interest. But the last year’s bill is forecast to be less than $2,200, reflecting a much better future for her daughter Gwendolyn.

The forecast differences are worth summarizing:

In order for the third case to have a chance, Congress must stop spending billions of dollars to preserve a few jobs. More important, it must stop cutting taxes every two to four years in an attempt to buy everybody’s reelection. That is because taxes can be “cut” only when the budget is in surplus. When there is a deficit, then every “tax cut” is a tax postponement. Taxpayers don’t pay for the postponed taxes immediately, but the tax shortfalls accumulate in the national debt. In turn, we pay more interest on the debt—which goes on and on and on and on and on.