The Arithmetic of Life and Death (15 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

In other words, every “tax cut” in the twentieth century has really been a veiled tax increase. The accumulated cost of all of these generous “tax cuts” is trillions of dollars of past and future interest on the national debt.

We have left our children and grandchildren a legacy of

debt—the largest and most irresponsible debt in the history of mankind. Our only hope of forgiveness is to start repaying it. It means that, except in times of war or prolonged recession, the U.S. government must run an annual surplus every year until the debt is repaid.

Debts are not monuments. They should not last forever. They should be repaid. If, however, loans are allowed to exist in perpetuity, then so will the interest on them, which means that the cost of borrowing will be infinitely high.

The national debt is colossal, but it must not be turned into a monument. It can and should be paid in full. Until then, any new “tax cut” is really a tax increase. Until the national debt is history, there are two legitimate ways to cut taxes: reduce the cost of government or increase taxes. Until the national debt is repaid, there are no other responsible courses of action.

Even if we start to repay the national debt today, we will leave trillions of dollars in debt to future generations. This is money we spent on ourselves but which future generations never agreed to lend us. In fact, they were never even asked. That is called taxation without representation. Our founding fathers thought it was wrong. We should, too.

23

Personal Debt

“Let us all be happy to live within our means, even if we have to borrow the money to do it with.”

— CHARLES FARRAR BROWNE

L

oan companies advertise a lot on television these days, but they don’t sell credit. They sell privilege: the freedom to go anywhere, the money to buy anything, special discounts, and, of course, status.

Americans are willing to pay big for privilege, freedom, and status. There are more than 30,000 different credit cards available in the United States; the average American adult carries six of them. In 1996, we Americans paid an average of $3,900 per person in interest on credit card and installment debt. Our total debts added up to 95 percent of our income. We must have a lot of privilege and status.

In truth, the credit card companies, the bankers, and the mortgage lenders are not selling freedom or privilege or status. They are selling money. Since they are in the business of selling money, they expect to get more back than they

originally sold. The difference between how much they sell and how much they get back is called interest.

The borrower is the buyer. In order to get the money, the borrower signs a contract agreeing to pay the lender more, sometimes a lot more, than the amount borrowed. Except for credit cards, which have a very high interest rate, there is usually some form of security. Failure to repay an automobile loan, for example, will normally result in the loss of the vehicle along with a number of other unhappy consequences.

Reginald DeNiall, who enjoys an excellent credit rating, recently bought his youngest son, Billy Ray, a new Dodge pickup truck after he agreed to finish high school. Since Reginald is a congressman, he got a special deal on the loan. He borrowed 100 percent of the truck’s heavily discounted $20,000 price tag, to be repaid over four years at 10 percent interest compounded monthly. Over the full term of the loan, Reginald will pay more than $4,400 in interest on the pickup, or about 22 percent of the original purchase price. Billy Ray believes that this is a small price to pay for freedom and status. Reginald, of course, is actually paying the bill.

Regardless of what most of us may think about the high cost of borrowing, almost all of us have to borrow money in order to buy a house or a condominium. These days, the typical loan is for more than $100,000 and the term is 15 to 30 years. Over such a long period of time, the cost of the interest is so high that the mortgage lender ends up getting more money than the builder of the house.

But there are two important differences to consider. First, the U.S. government allows its citizens to deduct mortgage interest from taxable income, which significantly

reduces the cost of the loan. Second, houses tend to appreciate in value. So they can frequently (although not always) be sold for more than the purchase price. As a result, buying a home is generally (but not always) better than renting. However, if the house payment is too high, it can choke the cash flow out of anyone. And the fees for buying and selling a home are expensive, usually 5 percent to 7 percent of the purchase price. So most homes must be owned for quite a few years before a profit can be made on their sale.

Although Reginald’s elder son, Joe Bob DeNiall, has an excellent manufacturing job with a respected local firm, he can’t afford a condo yet. But he does have two major credit cards of his very own. As soon as he got the first one, he went right out and used it to get a $2,000 stereo. The interest on the credit card is 18 percent, or 1.5 percent per month. So Joe Bob has to pay the bank $30 per month in interest for the right to continue to use the stereo. But even though Joe Bob pays each monthly bill on time, the balance he owes on his credit cards keeps going up because he keeps charging more. Last month, he “bought” a new game system for his TV set—which he had charged the month before that.

If Joe Bob has a $5,000 credit limit on his two credit cards (his father is a congressman), and if he keeps them at the maximum balance for ten years, then he will pay a total of $9,000 in interest, almost twice as much as he originally borrowed. Moreover, he will have to earn $12,000 to $14,000 so he will have enough money after taxes to pay the $9,000 in interest. And he will still owe $5,000.

To young folks in particular, that first credit card is as precious as a puppy: It is cute and cuddly; it cries for attention;

it must be exercised frequently; and it’s fun to show off. Puppies, however, grow into dogs. If your loan portfolio has matured into Lassie, then your debt is your pal. But, if your cumulative interest load has grown into an 800-pound pit bull that consumes its own weight in cash every thirty days, you have a serious financial problem. You may need professional help.

It is more likely, though, that you can work your way out of debt’s doghouse. Start by replacing all of those credit cards with a debit card, which is less dangerous by nature. Otherwise, use cash. Or write a check. Or take a bath. Because, if you have to charge it, you can’t really afford it.

24

Investing Young

“Wealth has its advantages, and the case to the contrary, although often made, has never proved widely persuasive.”

— JOHN KENNETH GALBRAITH

A

ll but a lucky few have to save for retirement. Since the “golden years” are so far in the distance, many young people postpone this important activity until middle age. However, how much money you accumulate by retirement will depend upon three things: when you start saving, how much you manage to save each year, and how much your investments return over the long run. Of the three, when you start saving turns out to be the most important.

Cecilia Sharpe, who has a reputation for good financial sense throughout the community, began putting $2,000 in an IRA-approved mutual fund, which returns 7 percent per year, when she was only twenty-five years old. When she is sixty-five years old, that first year’s $2,000 investment will be worth almost $29,400 all by itself.

Feeling mortal on his forty-fifth birthday, Reginald

DeNiall decided to open an IRA and invest the same amount in the same mutual fund. Unfortunately, at age sixty-five, his $2,000 investment will be worth only a little more than $7,700.

Both invested exactly $2,000. They will each get exactly the same return per year. The length of Reginald’s investment will be exactly half as long as Cecilia’s. But the amount Reginald will have at retirement will be only 26 percent as much.

That’s because interest compounds. Compounding means that interest is paid not only on the original $2,000 investment each year but also on all of the interest that has accumulated over previous years. At 7 percent interest, for instance, $140 is added to Cecilia’s $2,000 investment at the end of the first year. But at the end of the second year, $149.80 is added—$140 for the original investment and $9.80 for the previous year’s $140 interest. This never seems like much in the beginning, so saving is easy to put off. But compounding pays off in the long run—because the amount of interest eventually exceeds the amount of the original investment. Over the very long run, in fact, accumulated interest dwarfs investment.

Consistency is just as critical as starting young. Cecilia has invested $2,000 in her 7 percent IRA every year so far and plans to continue investing the same amount every year until retirement. After forty years, her $80,000 investment will be worth more than $419,000.

Unwilling to face a retirement lifestyle inferior to Cecilia’s despite his twenty-year handicap, Reginald decided to invest $6,000 every year, three times as much as Cecilia. However, the CPA on his research staff quickly informed the congressman that he would still have only $263,000 in

his IRA at retirement (even if he could really afford to set aside as much as $6,000 per year, which was $4,000 more than he had managed to put into an IRA in any previous year).

This was a sad state of affairs. Those who knew Reginald’s competitive spirit feared that he would eventually resort to speculation on stock options, commodities, and low-grade bonds. The returns on such investments can be beguiling, sometimes as much as 30 percent or more. But because of their volatile nature, the high returns are often diluted by large losses.

Through his experience with Social Security legislation, however, Reginald was certain that he could catch up to Cecilia, no matter how late he started. As a member of Congress, Reginald also believed that he had a special insight into how certain segments of the economy would perform in the near-to-intermediate term. And he had the advantage of an excellent research staff.

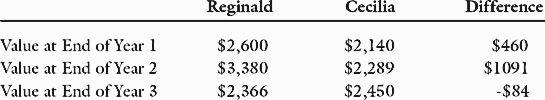

Once again, therefore, Reginald decided to amend his investment strategy by keeping his annual IRA contribution at a less painful $2,000 but investing it in high-risk stock and bond funds. In the ensuing two years, his IRA returned 30 percent per year on an annual investment of $2,000. In the third year, he lost 30 percent.

Compared to Cecilia, whose IRA continued to return an uninspiring 7 percent each and every year, Reginald’s three-year return was as follows:

Reginald was irate. He could not understand how he could make 30 percent per year in two out of three years but still underperform a paltry 7 percent per year. After all, three years at 7 percent was a total of only 21 percent, but his return over the same period had been 30 percent (30 percent in each of the first two years, less 30 percent in the third).