The Arithmetic of Life and Death (13 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

| Management Level | Number of Employees | Cumulative Employees |

| President | 1 | 1 |

| VP and Secretaries | 9 | 10 |

| Undersecretaries (9:1) | 81 | 91 |

| Commissioners (8:1) | 648 | 739 |

| Directors (8:1) | 5,184 | 5,923 |

| Managers (8:1) | 41,472 | 47,395 |

| Supervisors (8:1) | 331,776 | 379,171 |

| Actual Workers (8:1) | 2,654,208 | 3,033,379 |

This structure seems to create a lot of middle managers. But the advantages are:

- No employee is more than six persons removed from the Oval Office.

- The president is directly responsible for only eight appointments, the rest could be delegated to the vice president and the secretaries.

- The president has much more time to focus on meetings with key direct and indirect reports, especially during times of crisis.

- The president has more time to spend in intimate, win/win brainstorming sessions with representatives of the House and Senate.

- The size of the White House staff could be dramatically

reduced (the executive branch was originally intended to be the president’s staff) - Even after reorganization, less than 13 percent of the federal government would be middle managers (directors, managers, and supervisors).

In addition, the election of a Washington outsider would be less likely to become an overnight, full-employment program for the president-elect’s hometown.

Of course, presiding over the federal government and managing a business are not the same. No private sector CEO, for instance, has to deal with a Congress, approximately half of whom are habitually hostile to the aspirations of the president at any given time.

Maybe that’s why we have come to expect so much from our elected officials.

“None of us really understands what’s going on with all these numbers.”

— DAVID STOCKMAN (ON THE 1981 FEDERAL BUDGET)

20

Figures Don’t Lie …

“Mathematics may be defined as the subject in which we never know what we are talking about, nor whether what we are saying is true.”

—BERTRAND RUSSELL

J

ust like cereal and cigarettes, numbers are packaged for the convenience of the consumer audience. But there are few truth-in-labeling laws for numbers, so the czars of marketing have plenty of room for creativity.

A few years ago, and shortly after a costly and embarrassing confrontation with an entrenched tree stump, Reginald DeNiall decided to sell his software company. Given the company’s rapid growth during his administration, he was confident that he could get a very good price, especially within the high-technology industry. So, like all good CEOs, Reginald set about preparing his organization for sale. First, he divorced his wife, who was also his controller, and replaced her in the company with a high-powered chief financial officer (called a CFO in the trade) who had recently been a consultant with an important eastern firm.

Reginald and the new CFO then drafted a prospectus, which is a lot like a brochure, only it is specifically for the sale of a company. The cover letter of the prospectus did an excellent job of extolling the virtues of the company’s performance over the previous four years, which included:

- three consecutive years of profitability;

- average growth of 35 percent in the previous four years; and

- a 9 percent reduction in expenses in the last twelve months.

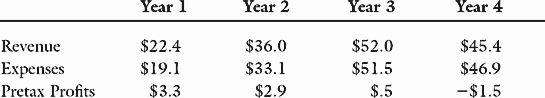

A dozen major software companies and independent investors examined Reginald’s company closely. However, despite the excellent prospectus, the upgraded management team, and the obvious benefits of Reginald’s focus on company growth, they all declined the acquisition. A contributing factor was the company’s actual financial performance during Reginald’s presidency, which was as follows (in millions of dollars):

Although everything that Reginald claimed in the prospectus was true, the company’s actual financial performance had been somewhat different:

- Profits had declined for three consecutive years, from a very respectable 14.7 percent of revenues in Reginald’s

first year as CEO to a 3.3 percent loss in his final year; - Growth, which had averaged more than 50 percent in the previous two years, had reversed to a 13 percent decline in the last twelve months; and

- Expenses were dropping, but they were dropping more slowly than revenues, leading potential investors to predict even greater losses in the years ahead.

Being a man of conviction, Reginald eventually sold the company to a Swiss confectioner at a price much lower than he’d hoped, then wrote a book and subsequently joined the investment banking firm that had helped him to complete the sale. Shortly thereafter, with the support of both his new employer and his political party, Reginald managed to place himself on the ballot for a congressional seat that had recently become vacant due to the usual sex scandal.

Reginald’s opponent in the primary was a clean-cut health nut, which would not have mattered much except that Reginald, who reads for exercise, is from a state in the Pacific Northwest that is chock-full of health nuts who vote.

As the primary neared, the opponent moved ahead of Reginald in the polls, thanks to a simple television campaign in which he jogged down a typical neighborhood street, dressed in a patriotic, blue and green “Go Mariners” sweat suit, while he emphasized his fitness for the job of congressman. Everywhere Reginald looked, he saw his opponent on a billboard in a jogging suit. Every time he turned on the television, Reginald saw his opponent running on at the mouth about fitness for Congress.

Reginald, who had come to believe that integrity was a

communications tool, did not see how he could possibly lose to an anonymous, kid liberal whose principal virtue was exercise. But as election day neared and the gap widened to three percentage points in the polls, Reginald became more and more depressed.

Then, on a dark and dreary night about two weeks before the primary, Reginald happened to be watching the eleven o’clock news on KWET, an independent television station north of Seattle. The headline story, and the first ten minutes of the broadcast, were solely devoted to the plight of the state’s recently elected governor. It featured an in-depth studio report, a broadcast from the governor’s mansion, a historical perspective, several “expert interviews,” and an “on the scene” update from a picturesque Colorado hospital—all to report that the new governor had fractured his arm in a skiing accident.

Reginald’s mood was transformed by the media’s enthusiasm for the governor’s minor mishap. He picked up the telephone and called his campaign manager, who had formerly been his CFO. That same night, after thoroughly analyzing the situation, the two of them concluded that Reginald could still win the primary if they could find a way to defeat the core virtue of his rival’s campaign: his fitness ethic.

The campaign manager immediately launched an in-depth investigation of his opponent’s habits. In the meantime, Reginald’s media director prepared the press for the possibility of a small but significant scandal. Then, two days before the election, Reginald’s team leaked its findings to an animated and eager media community.

One day before the election:

- The local television news reported that the candidate’s exercise routine was a model of inconsistency in which he exercised twice in three days, then once in the next four.

- A cable network talk show reported that Reginald’s opponent, who claimed to be a fitness fanatic, actually exercised less than 3 percent of the time.

- An editorial in the state’s most influential newspaper reported that Reginald’s opponent went three days per week without exercising at all.

- A radio network reported that he often exercised only once in five days.

Reginald, of course, was dismayed to learn that his opponent, who was so prideful of his fitness focus, could have such a lightweight exercise routine. In the hours leading up to the primary, he managed to convey the message many times in a statewide media blitz.

In his concession speech immediately following the election, Reginald’s opponent detailed his exercise regimen to the press. It turned out that he completed a rigorous, ninety-minute routine that included calisthenics, free weights, and a two-mile run, between six and seven-thirty

A.M

. every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday.

A junior reporter for a suburban newspaper later figured out that all three exercise routines were actually completed in an elapsed time of 97.5 hours (four days plus 1.5 hours). That meant that the losing candidate did not exercise at all for 70.5 hours, which is 2.9375 days and which rounds easily to three. In addition, two of the three routines were completed in only 49.5 hours, which meant that there was

only one routine in the next 118.5 hours, which was 4.9375 days. Unfortunately, the newspaper’s editor did not elect to publish the reporter’s findings since it was not at all clear that the article would maximize the wealth of the parent company’s shareholders by increasing circulation.

Reginald had his agendas. So do the media, business, and charity. Always exercise caution when dealing with any numbers that they package for your consumption. Better yet, take a few moments to add them up for yourself.

21