The Arithmetic of Life and Death (8 page)

Read The Arithmetic of Life and Death Online

Authors: George Shaffner

Tags: #Philosophy, #Movements, #Phenomenology, #Pragmatism, #Logic

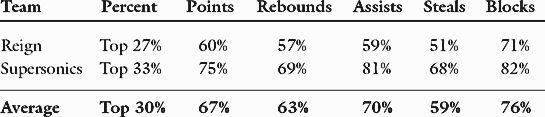

Thus, although the 80/20 Rule seemed to be in error, it began to appear to Cecilia that there might be some basis for a 70/30 Rule, or maybe a 60/30 Rule. However, even this seemed like more of a productivity gap than could be naturally explained, so Cecilia decided to research relative player production in each of several other statistically important categories in basketball:

Overall, the top 30 percent of the team in each category produced about two-thirds (67 percent) of the results. Before presenting her findings to the managing partner, though, Cecilia decided to test two other team sports. In baseball, Cecilia found that the top 30.4 percent of the Seattle Mariners in each batting category (excluding all pitchers) produced 70.4 percent of the runs, 69.9 percent of the hits, 78.2 percent of the home runs, and 74.4 percent of the runs batted in. In hockey, Cecilia found that the top 30 percent of the Vancouver Canucks were responsible for 65.8 percent of the goals and 59.4 percent of the assists.

Balancing performance across all four teams produced the following results:

| Team | Top Percent | Average Productivity |

| Reign | 27.3% | 59.6% |

| Supersonics | 33.3% | 75.0% |

| Mariners | 30.4% | 73.2% |

| Canucks | 30.0% | 62.6% |

| TOTALS | 30.2% | 67.6% |

When confronted with the numbers, the managing partner had to conclude that the 80/20 Rule was probably invalid, at least when applied to employee productivity. But Cecilia had to concede that it was only a slight exaggeration from the more accurate, but less assonant, 67/30 Rule. While he reached into his wallet for a one-dollar bill, Cecilia restructured her “cotton picking” model:

- Again, ten cotton pickers picked 100 bales of cotton;

- But, according to the 67/30 Rule, the top three pickers picked sixty-seven bales of cotton; and

- The bottom seven pickers picked only thirty-three bales of cotton.

- So the top three pickers produced an average of 23.33 bales each; but

- The bottom seven pickers produced an average of only 4.714 bales each;

- So the top three pickers were still 4.9 times as productive as the bottom seven pickers (23.33 ÷ 4.714)!

Although happy to win the bet, Cecilia still found the result bothersome. In all of the sporting cases, the star players had substantially more playing time than the rest of the team, which must have skewed raw productivity in their favor. But in business, she noted, practically everyone worked the same forty- to sixty-hour workweek.

Once again, the managing partner disagreed. In his opinion, giving the most time to star players was the definition of good management and any deviation toward equality of opportunity was certain to cause overall team productivity to plummet.

Fearful that the managing partner might use the 67/30 Rule as an excuse to downsize the business, Cecilia asked for time to revisit personal productivity by equalizing opportunity for all of the players on each team. The managing partner was happy to accept her offer—but double or nothing on the original bet if overall productivity fell by 10 percent or more after equalization, since even such a small dip would erase the profitability of many businesses.

12

Equalized Opportunity

“… a fair chance, in the race of life.”

— ABRAHAM LINCOLN

D

espite the “discovery” of an improved 67/30 Rule of Thumb (from the previous chapter), Cecilia was convinced that inequality in opportunity had distorted the productivity gap between players on the teams that she had researched. So, with a firm lack of support from her managing partner, she returned to her sports models in search of resolution.

First, Cecilia decided to equalize the 1997/1998 playing time of all of the players on the roster of her once favorite but now obsolete basketball team, the Seattle Reign. Since the eleven members of the team had played a total of 8,850 minutes in their one full season, it was a simple matter to adjust every player’s point production as if each had played exactly 804.5 minutes each. When she did, the player productivity picture changed remarkably:

| Player | Total Points Before Equalization | Total Points After Equalization |

| Enis | 754 | 454 |

| Whiting | 645 | 375 |

| Starbird | 557 | 304 |

| Paye | 300 | 188 |

| Aycock | 269 | 211 |

| Ndiaye | 195 | 408 |

| Holmes | 195 | 214 |

| Smith | 93 | 276 |

| Godby | 73 | 356 |

| Hedgpeth | 85 | 204 |

| Orr | 89 | 157 |

| Team Total | 3,255 | 3,147 |

Contrary to even her own expectations, total Reign point production fell only 108 points, just 2.45 points per game. Although that might have been a significant factor in professional sports, it would have been no more than a simple 3.3 percent productivity drop in business, and one which might have been more than offset by a reduced dependence on “star” salaries.

In addition, the identity of the stars seemed to change somewhat after equalization: The top 27.3 percent of the team’s shooters were Shalonda Enis, Astou Ndiaye, and Val Whiting, but they scored only 39.3 percent of the points, compared to 60.1 percent in the nonequalized model.

Next, Cecilia equalized the playing time of all fifteen Seattle Supersonics to 1,314.9 minutes each, producing the following:

| Player | Total Points | Equalized Points |

| Baker | 1,574 | 703 |

| Payton | 1,571 | 657 |

| Schrempf | 1,232 | 591 |

| Ellis | 932 | 632 |

| Hawkins | 862 | 436 |

| Perkins | 580 | 455 |

| Kersey | 234 | 429 |

| Anthony | 419 | 540 |

| Williams | 298 | 518 |

| McMillan | 62 | 292 |

| McIlvaine | 247 | 268 |

| Cotton | 24 | 956 |

| Wingate | 150 | 361 |

| Zidek | 29 | 596 |

| Howard | 25 | 620 |

| Total | 8,239 | 8,054 |

In the case of the Supersonics, team point productivity dropped by 185 points, or 2.2 percent, which was even less than the Reign. After equalization, point productivity of the top five players (33.3 percent of the team) was just 44.3 percent of the team total.

Cecilia then equalized performance for both the Reign and the Supersonics across the same five measurements that she used in her original analyses:

Equalized Opportunity Model

With the early results counted, Cecilia began to feel confident that something like a 50/30 Rule was a far more accurate representation of equal opportunity than 67/30 or 80/20. Further analysis tended to confirm her hypothesis.

After equalizing the 1997/1998 Mariners baseball team to 239.4 at bats each, Cecilia discovered that the team batting average dropped from .275 to .252 as the number of hits fell to 1,390 from 1,515, an 8.3 percent drop, and home runs fell from 239 to 163 (down 31.8 percent). But total runs scored, which was the most material measurement of team productivity, dropped only 2.9 percent, from 800 to 777. The effects of equalization on top player performance were also similar to her first two analyses, with the top seven (30.4 percent) Mariners producing 38.4 percent of the runs, 36.5 percent of the hits, 59.6 percent of the home runs, and 45.4 percent of the runs batted in.

Finally, Cecilia equalized opportunity for all of the hockey players on the 1997/1998 Vancouver Canucks to 82.4 shots on goal. As a result, total team goals fell from 193 to 182.7, a drop of 5.3 percent, but assists rose from 286 to 295.9, a 3.4 percent increase. After equalization, the top 30 percent of the team produced 38.2 percent of the goals and 46.8 percent of the assists.

Cecilia was led to two conclusions. The first was that, despite significant drops in secondary measures such as shots blocked and home runs, equalization of player opportunity had had a smaller negative effect on primary productivity measures than she had expected:

| Team | Measurement | Productivity Drop |

| Reign | Points | 3.3% |

| Supersonics | Points | 2.2% |

| Mariners | Runs | 2.9% |

| Canucks | Goals | 5.3% |

| AVERAGE PRODUCTIVITY | LOSS | 3.4% |

Cecilia’s second conclusion was that, by equalizing opportunity, the 67/30 Rule had collapsed to a figure nearer to 47/30:

EQUALIZED OPPORTUNITY MODEL